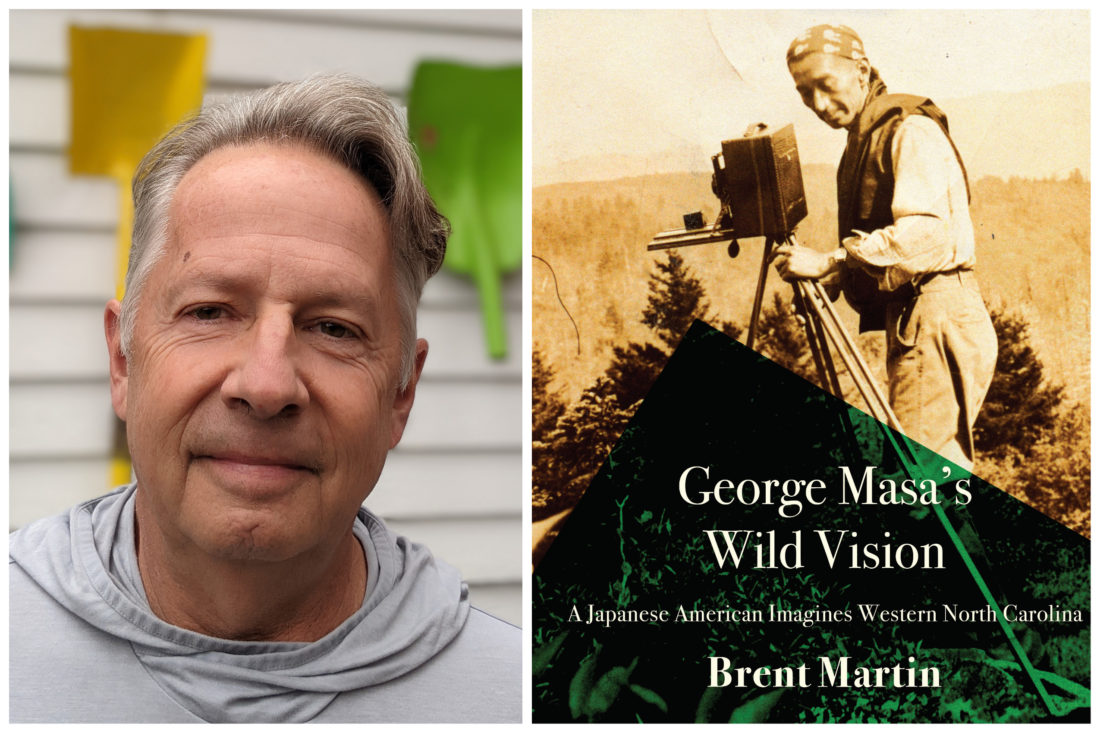

In many cases, books inspire films. But for Brent Martin’s soon-to-be-published George Masa’s Wild Vision: A Japanese Immigrant Imagines Western North Carolina, it was the other way around.

A poet and environmental organizer based in the Cowee community in Macon County, Martin first developed an interest in the photographer after seeing Asheville-based director Paul Bonesteel’s 2002 documentary, The Mystery of George Masa. Born Masahara Iizuka in Osaka, Japan, Masa arrived in California in 1901 to study mining, then came to Asheville in 1915 and worked service jobs at the Grove Park Inn. Soon thereafter, he began taking pictures for the hotel and eventually turned photography into a full-time career. Despite all this, Masa died in 1933 of tuberculosis, destitute and largely unknown.

In the wake of Bonesteel’s film, Martin learned more about the man many called the Ansel Adams of the Smokies. Ken Burns’ documentary The National Parks: America’s Best Idea and William Hart Jr.‘s essay “George Masa: The Best Mountaineer” shaded in more details, as did George Ellison and Janet McCue’s 2019 book, Back of Beyond: A Horace Kephart Biography, which includes a chapter on Masa and his work with Kephart to help create Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

However, writing a book on Masa wasn’t Martin’s goal. He spoke with Hart about doing some kind of project on the photographer. But other than taking what Martin calls “pretty significant journeys” into parts of the Smokies that Masa photographed and viewing and reading about those images to help inform his 2019 collection, The Changing Blue Ridge Mountains: Essays on Journeys Past and Present, he had yet to write much about the photographer. Then, shortly before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Martin was approached by John Lane and Betsy Teter of Hub City Press to create a photographic essay collection about Masa.

“It was a gift to me to do this,” Martin says. “I felt intimidated by it because of how much work [Bonesteel] had done, but I wanted to take a different approach and not just regurgitate what he and others had done.”

Into the woods

After Martin’s initial discussions with Lane and Teter, he says he “dove into” the existing research on Masa and began tracking down his subject’s photographs, which are spread out across different institutions, universities and nonprofits. Once he finalized his contract in March 2020, Martin turned his attention to the book’s framework.

Trekking to the spots Masa lensed a century prior, Martin found inspiration for his text amid the current global health crisis as well as the racial equity work led by the Black Lives Matter movement. In the early days of lockdown, he adds, crowds of people were flocking to WNC to spend time in the outdoors — a fact that also inspired the writer.

“I couldn’t do this book without contextualizing it in the current 21st-century medical crises,” Martin says. “I was trying to get a keen sense of what Masa saw 100 years ago that’s so different now and what he thought this place would be like in 100 years.”

Those stark changes were especially evident in summer 2020, when Martin went to find Masa Knob, the 6,217-foot peak with a subtle 175-foot prominence on the North Carolina/Tennessee border that GSMNP dedicated to the photographer in 1961. The site is difficult to find and requires bushwhacking to reach, so Martin recruited two friends familiar with its location to guide him. The three started from nearby Newfound Gap.

In preparation for the hike, Martin was mindful of photos that Masa took of Newfound Gap. At that time, it was a rugged, single-track gravel road that the photographer was documenting while he and Kephart were mapping out the Appalachian Trail. But when Martin pulled into the Newfound Gap parking lot, he had difficulty finding an open spot.

“It was just interesting to see the park 100 years later, just so overrun with people, and to hike out to Masa Knob and be away from the crowd and be in that quiet place — a little peak named after him — and just wonder if he went to the top of it,” Martin says.

Further fueling Martin’s writing was his contemplation of the immigrant experience in the South. Though Masa was able to explore the mountains of WNC with considerable ease, he still experienced rampant racism during a time when anti-Japanese/Asian immigration laws were passed. (As reported in the book, Grove Park Inn manager Fred Loring Seely was suspicious of Masa’s photography and journal-writing and reported him to the FBI as a potential spy. He later urged the matter to be dropped, citing Masa’s plans to remain under his employment.) Masa also photographed Stone Mountain when the Confederate memorial was being carved, which Martin feels had to have been a strange, uncomfortable experience.

While working on the book, six Asian Americans were killed in the Atlanta spa shootings of March 2020, reminding Martin that while much has changed since Masa’s time, much has also remained the same. Noting that all but indigenous people are immigrants, Martin thought it was important to acknowledge Masa’s and others’ journeys with the book’s dedication “to the millions of immigrants who took risks pursuing their dreams to enter this country, and to those who continue to do so.”

Legacy in progress

George Masa’s Wild Vision will be published Tuesday, June 21, and features 75 images from the photographer’s 400-plus surviving shots — a selection process that Martin describes as “daunting.” He hopes that people who read it come away with a greater respect for our natural landscapes and how they’ve changed over time and an enhanced appreciation of Masa’s stunning work.

These efforts will eventually be joined by additional scholarship as Bonesteel and McCue are currently working on a new Masa biography. Martin says his colleagues have hired a Japanese archivist and researchers to help fill in the historical gaps of Masa’s life since so little is known about his time in Japan. Martin is looking forward to their findings and is honored to have helped tell Masa’s story, the mysteries of which continue to cast a spell on him.

“It was a hard book to quit writing. I felt like, ‘Wow, this journey just keeps going on,’” he says. “I guess that’s the good thing about deadlines — you’ve got to end it.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.