By Sally Kestin, Asheville Watchdog

A national consultant hired to advise Asheville on its highly visible homeless population stood before elected leaders last month with a bold proclamation for a plan she described as a “road map of how to end homelessness in your community.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, many of those who participated in and followed the work of the Washington, D.C.-based National Alliance to End Homelessness were skeptical.

“This was a sham,” said Micheal Woods, executive director of the nonprofit Western Carolina Rescue Ministries. “We brought in the National Alliance to End Homelessness and paid them $73,000 to tell us to keep doing what we’re doing.”

Some of the findings, like a shortage of affordable housing and high cost of living, were obvious to anyone who’s lived or worked in Asheville.

“You’re telling us we’ve got to put more people into housing, and we’ve been talking about affordable housing for 20 years,” Woods said.

Some of the people most affected by homelessness — including those working in the field, business owners and the unhoused themselves — had lost faith in Asheville’s ability to make any significant difference even before the anticipated “Within Reach: Ending Unsheltered Homelessness” report came out Jan. 20.

In hundreds of interviews and surveys the consultant conducted, “Community members reported a loss of trust and belief in the ability of elected officials, city, and county staff to have any real impact on homelessness.”

Steady stream of homelessness

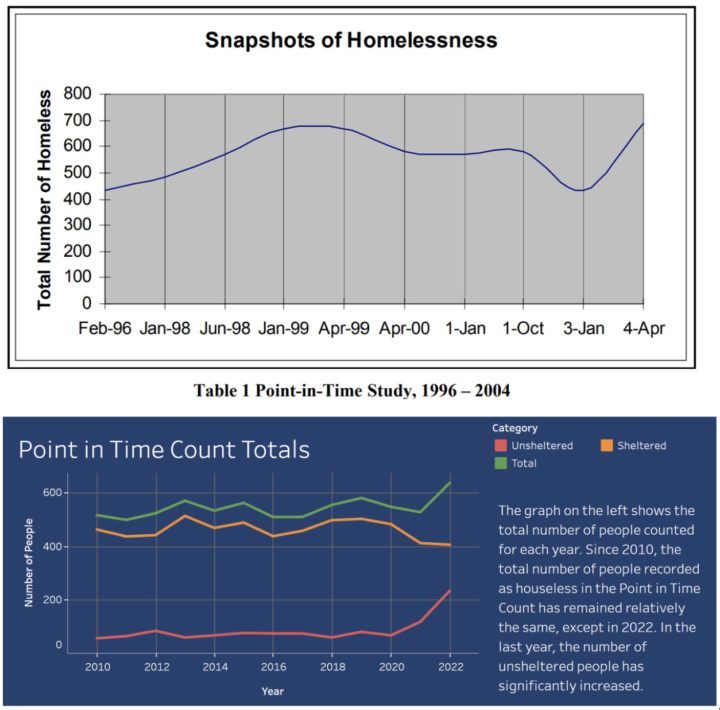

The population of homeless people in Asheville has remained about the same for at least 25 years: generally, 500-600 annually but higher in some years, despite local government spending millions of dollars and making pledges to reduce or end homelessness altogether.

In 2004-05, facing concerns similar to today’s, local government and community leaders met for six months and produced a report titled, “Looking Homeward: The 10-Year Plan to End Homelessness” in Asheville and Buncombe County.

Back then, Asheville’s homeless population was 689. The latest count, as of January 2022, was 637. The 2023 “point-in-time” census was counted Jan. 31, but results won’t be released until spring.

Buncombe County Commissioner Terri Wells said she is “not interested in focusing on the past reports or what other leaders did or didn’t do.”

With “strong community collaboration,” Wells said, “we will achieve a significant reduction in unsheltered homelessness.”

Tents, drugs and complaints

Nearly two decades ago, it was the chronically homeless that prompted the 2005 report with its erroneous prediction: “‘Looking Homeward’ will end chronic homelessness and reduce all types of homelessness over the next decade.”

By 2022, Asheville had 211 chronically homeless people and a doubling over the previous year of unsheltered people living on the streets, in tents or in cars, often with mental illnesses and/or drug and alcohol addictions.

Tent encampments popped up along highways and rivers and under overpasses. Homeless people behaved erratically, fueled by especially potent drugs like fentanyl and methamphetamine, generating complaints from business owners, tourists and downtown visitors.

“Many people expressed concern about public safety decreasing and their families ‘being afraid’ to be out in the community,” the alliance’s report said. Those experiencing homelessness also reported feeling unsafe.

So, in May 2022, the city and county agreed to seek “national expertise” and hired the nonprofit alliance to “guide the county’s work on homelessness.” Dogwood Health Trust paid the $72,974 cost.

‘Nowhere to go’

So, what did Asheville get for its money, and how realistic is the plan?

The main goal the alliance recommended — cutting the unsheltered population in half in two years — is likely doable with projects that were already underway.

The number of unsheltered as of January 2022 was 232. Nearly 200 more beds are scheduled to become available this year with the conversion of two former hotels, the Days Inn on Tunnel Road and the Ramada Inn on River Ford Parkway.

“Those projects will certainly help,” Emily Ball, Asheville’s homeless strategy division manager, told Asheville Watchdog via email. “They are dedicated to people who are chronically homeless, many of whom are unsheltered.”

The alliance also recommended providing rental assistance for an additional 200 homeless single adults and 50 families to quickly find housing and adding 95 temporary shelter beds.

A more immediate need, Woods said, should be safe apartments and housing — both public and private — for people already in shelters.

“I have 110 people that are in my shelter that are working every day, that are saving money, that are ready to be housed, but they have nowhere to go,” Woods said. “When they apply for market-rate housing, because of the demand in the area, because of something on their past credit or maybe past criminal history, they get looked over, so they’re having to stay in shelter … a whole lot longer than what they really need.”

Asheville’s public housing, Woods said, has too much crime, including drug dealing and shootings.

“We have people living in public housing that I talk with that are absolutely afraid for their lives,” he said. “I know families in Hillcrest who literally every evening lay on the floor. Their grandchildren sleep in the bathtub because of the gun violence.”

New model gets support

One recommendation that seems to have widespread support is a change in the leadership and oversight of Asheville’s homeless response, which is currently housed under the city and managed by a committee of 16 with eight members appointed each by the City Council and county Board of Commissioners.

In other places like Houston, often held up as a national model for reducing homelessness, a nonprofit agency independent of local government oversees homelessness and includes representation and buy-in from the many organizations involved in the work, as well as previously homeless people.

The goal is to promote coordination “so everybody is sort of rowing in the same direction,” Ann Oliva, the alliance’s CEO, told Asheville and Buncombe elected officials at a meeting Jan. 25.

“We’ve been calling for that for a number of years,” said Scott Rogers, executive director of the Asheville Buncombe Community Christian Ministry.

Another benefit of the proposed change, said Marcus Laws, homeless services director at Homeward Bound: “It offers an opportunity to take politics out of it.”

“We as agencies have to do better about working together,” Laws said.

‘Critical lack’ of data and coordination

Oliva told the elected officials that “lots of good work” is being done around homelessness in Asheville, but it’s “not fully coordinated.”

One reason, the alliance found, is a “critical lack” of data about the unhoused, the services they’re receiving or needing and what’s working.

The federal Department of Housing and Urban Development requires local governments and agencies that receive HUD money for homelessness to track people and services in the Homeless Management Information System.

But “only about 66% of service providers in Asheville-Buncombe County provide entry and exit data into the HMIS database,” the consultant’s report said. “This represents a critical lack of information about those who may want and need housing and services in the community and the lack of available housing interventions.”

Ball, Asheville’s homeless strategy manager, told Asheville Watchdog that the VA Medical Center does not participate in HMIS but does capture information about homeless veterans in a different federally mandated system. “We have a manual workaround in progress to include their data in HMIS,” she said.

Two other agencies that serve the homeless do not use the database, Swannanoa Valley Christian Ministry, which operates a transitional housing program, and Western Carolina Rescue Ministries, Ball said.

Woods said the Rescue Ministries staff collects the data — and more — in a separate system and is willing to provide it anytime or allow the city to tap into his database for a fee.

Participation in the HMIS should be mandatory, the consultant said.

The Houston nonprofit that oversees homelessness in that city includes a representative from a university that analyzes data and committees that ensure its “data is solid,” Oliva said.

San Diego, a place that Oliva said more closely aligns with Asheville, publicly posts live data on its unhoused. “They look at their data every single day,” she said.

Money flows, but how much?

Another shortcoming of Asheville’s system: A lot of money is going toward homelessness, but no central entity tracks the total or coordinates where best to spend it.

The federal and local governments currently provide $3.3 million annually, and this year, the city and county received $23.8 million in COVID-19 relief money that went toward homeless services and housing.

On top of that is additional federal funding for veterans and private donations to the many nonprofits operating shelters, providing housing and helping people on the streets.

Homeward Bound has raised more than $15 million through public and private sources for the purchase and conversion of the Days Inn into housing for 85 chronically homeless people.

ABCCM recently built housing for 100 homeless women, children and veterans, and “raised $13 million entirely from the private sector,” said Rogers, the director.

The current city-county advisory committee decides how to spend one piece, the federal homelessness funding. Asheville should track all the money to ensure it’s used “systemically and not funding ad hoc projects,” the alliance said.

In all, the consultant’s recommendations, primarily for the increase in rental assistance and shelter beds, will cost an additional $6 million, according to estimates in the report.

‘Got to keep trying’

Asheville Watchdog asked all Asheville City Council members and Buncombe County commissioners about the consultant’s proposals. Only Wells and Commissioner Parker Sloan responded by deadline.

Wells said she wants to see a timeline with costs. “In order to make a significant impact, we must address multiple aspects of this issue with urgency,” she said. “Prevention and diversion measures are key.”

Sloan said that “homelessness is a policy choice, and we have built a society that allows it to happen.”

“We can provide people with health care, with addiction treatment, a basic guaranteed income, public safety and make sure they have housing,” he said. “Our society is already spending money on these things; we just do it in a needlessly punitive, unintentional and inefficient way.”

Sloan said the new leadership structure “may be the biggest benefit” of the consultant’s report. “My hope is that we make a number of different choices so that my kids don’t have to have this same conversation 20 years from now.”

Jerome Jones, a former Buncombe County assistant manager, chaired the committee that produced the 2005 plan to end homelessness in Asheville.

He said homelessness has remained a pervasive problem in most cities because of a lack of affordable housing, and “an endless supply of people in need … because of our economy, because of our lack of a social network, because of our ‘don’t give a damn about poor people that are homeless.’”

“I think it’s not a matter of a lot of good hasn’t been done,” Jones said.

He said he titled the 2005 report an “end to homelessness,” knowing “that wasn’t going to happen.”

“A lot of people did beat homelessness, people did get their lives together, people did get services they hadn’t been getting,” said Jones, who retired and now lives in Madison, Wis.

And given that the number of unhoused people in Buncombe has stayed relatively flat since 2000 while the county’s population grew by 33%, Jones said, is “a big win.”

“It’s never going to be zero,” Jones said. “I think you simply can’t say we’re going to let this population just stay the way they are. We’ve got to keep trying.”

Asheville Watchdog is a nonprofit news team producing stories that matter to Asheville and Buncombe County. Sally Kestin is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter. Email skestin@avlwatchdog.org.

Again. Says it all.

The fact that the NAEH study omitted a pie chart showing at least 30 percent of the local homeless were Citizens with Disabilities (CWDs) in 2022 is more than a mistake. It’s denying CWDs housing. It’s possibly unlawful under the ADA as municipal conduct of the nature is covered.

The term CWD comes from the Mayor’s Committee on Citizens with Disabilities… which most likely hasn’t actually met since the Bellamy Administration… so Esther and Debra had a chance in the past to delete the MCCD from the City of Asheville website.

https://www.ashevillenc.gov/government/mayors-committees/

If we ever hire a consultant to tell us that Tourism and too much TDA advertising is the root cause of all of our troubles, I’ll sit up and listen. Until then, I’ll just watch the clown car careen off the cliff.

Tourism isn’t the problem. It’s been a the largest benefactor of WNC’s economy for over 100 years. Inept leadership is to blame.

Asheville Watchdog is great at spotlighting and analyzing many local problems. Its coverage of the fiasco and malfeasance connected to the sale of Mission to HCA is particularly noteworthy. But I’m curious to know if there is ever any follow-up where some group takes action to rectify the situation Watchdog has reported? Dr, Peter Gentling made this plea in the Asheville Citizen-Times not too long ago: “We all want our fine nonprofit hospital back with private physicians and adequate staff. Reverse, nullify, the purchase. Return the Dogwood Trust funds to HCA. If this cannot take place, then HCA owes the Dogwood Trust an additional $3.5 billion it should have paid in the first place.” Are any concerned citizens, doctors, etc, leading such an effort? If not, why not?

I’ve also wondered about follow-up articles on several local stories including but not limited to: the recent Asheville Museum debacle, the Florida tourists who OD’ed at the Grove Park last year (further draining our limited resources) but apparently weren’t charged, the carbon footprint of our wonderful tourism industry, etc.