Regular readers of Xpress‘ monthly poetry feature may recognize Mildred Kiconco Barya‘s name. In April 2021, she served as judge for the paper’s semiannual poetry contest. The following year, she shared her work, “Falling in Love” as part of April’s Poetry Month print series.

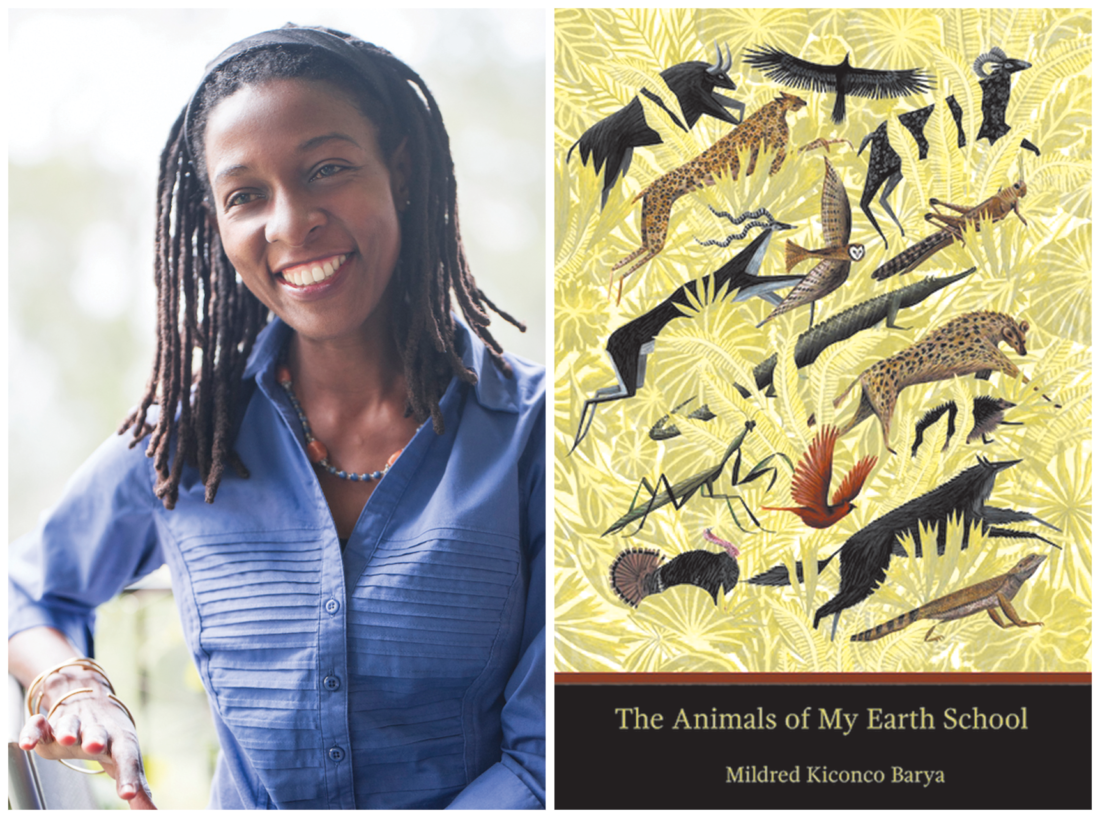

This time around, the local poet and assistant professor of English at UNC Asheville is celebrating the April 10 release of her latest collection, The Animals of My Earth School. Barya will be in conversation with fellow poet Tina Barr on Sunday, April 16, at 5 p.m. at Malaprop’s Bookstore/Cafe. The celebration continues Saturday, April 22, at 5:30 p.m. with a book release event at Story Parlor.

Barya’s poem “Guilted Tenderness,” which is featured in her new collection, appears below. Along with sharing her latest work, the poet also took time to share her thoughts on the state of poetry, its role in addressing environmental concerns and the poets who inspire her.

Guilted Tenderness

Mother cow gives birth to a small baby.

A few hours later the calf struggles to stand.

Mother licks it clean and moves her teats

closer, but it’s ignorant of suckling.

A man in black work boots and faded blue

overalls brings a lump of moldy cheese,

perhaps to trigger its sense of smell,

but the calf declines to eat. Then the

man pushes into its mouth what looks

like breadcrumbs. Still, the calf won’t feed.

A rush of compassion washes over me. We

were all once like that, newly born and helpless.

Some babies instinctively know how to suckle.

Others have to be nudged. I walk away feeling

tender, wishing for the calf to grow strong as

we drink the milk and replenish with colostrum.

Xpress: Thanks for sharing this piece. Can you speak to its inspiration?

Barya: I “received” a chunk of this poem in a vivid dream that profoundly moved me. When I woke up close to tears, I decided to write the scene in couplets. I was not satisfied with the ending I had then. Sometimes, I go through several drafts, so I knew I’d revisit the poem months down the road.

I wasn’t thinking of the poem or revision when the last line came to me. I was reading an online article about probiotics and other supplements when I came across colostrum. Odd, I thought, that we humans use the milk that should be drunk by newly born calves to boost and sustain our immune systems. It felt like taking milk out of the mouths of babes.

That is fascinating that the poem came to you in a dream. Do dreams factor into other poems you’ve written, or was this a first?

This is not the first time that dreams have appeared in my poems or hybrids. I have a manuscript of dream poems and journals; I keep wondering what to do with them. I like the surreal quality. And when I think of the times we’ve gone through with the pandemic, followed by the Russian invasion of Ukraine — I can’t wrap my head around developed nations choosing war just when you think we all ought to be appreciating life more — I review my dreams and realize that they aren’t so strange, after all. Our current local and global realities are more incongruous, terrifying and incomprehensible.

Circling back to your previous point, I’d love to hear more about your approach to revision. It sounds like you are a patient poet, in that you recognize and know you’ll be revisiting a piece several months after the fact. Is this a standard approach to each of your poems, or is it more case by case?

Years of practice and a dose of maturity have modified my understanding of creation — it’s never finished. But there’s a “feeling” point at which the poet decides to let go. The writing life has a lot in common with love, and the passage of time is a good rule of thumb. I prefer to revisit what I write a month or so later, sometimes several months in between. If it occurs to me that it’s still got all the elements that make a poem or piece of prose intelligible and meaningful, chances are it’s really great. It’s lived up to its promise.

However, if I read and feel like the piece could use some improvement in tone, diction, figures of speech or structure, then it’s best to tinker with it. Even in cases when a first draft seems juiced up with nectar from the gods, I do not hit the submit button. I put it aside to see what my senses might make of it after the initial euphoria has passed. All this, to avoid the embarrassment of publishing a piece that may not be ready.

Nature features prominently in many of your works, including “Guilted Tenderness.” Since this poem is appearing amid our Sustainability series, could you speak to your own views on issues concerning the topic and what, if at all, the poet’s role can be in engaging in the issue through their work?

I love this question. Sustainability has become a way of life for me. It used to be a value, but now I’ve taken it a notch higher. I ask myself each time I’m presented with a choice or task: Is this sustainable? Is what I’m doing or asked to give at any moment sustainable? If my answer is not a resounding “yes,” I let that pass.

As you can imagine, with this new way of being I may be left with only animals for friends, but it’s the right approach to simplifying my life. I sincerely think that if we all asked ourselves, not just the poets, if whatever we’re engaged in is sustainable — whichever way we interpret sustainability — there would be less waste, less time-consuming activities that don’t truly nourish anyone, and we could bring back a quality of life that’s in balance with all that is.

Is the issue of sustainability itself something you intentionally explore in some poems? Or do you prefer to enter your work without a concrete message in mind?

Mostly the latter. I’m aware of the tendency to get heavy-handed when I approach writing with a concrete message in mind. If doing so doesn’t block the flow (which is how I define a writer’s block), then, fine — as long as the writing isn’t contrived. To avoid self-created blockages, I prefer to come up with a general idea or overarching theme such as appreciation of life or the natural world. This holds the promise of branching out into several interesting angles that free my imagination and, perhaps, facilitate each reader to bring out of a poem a different message.

On the other hand — and this might seem like a contradiction — my creative nonfiction essays are invested in social justice issues and have specific themes of identity, belonging and the meaning of home. Maybe the best way to answer your question is through form and a consideration of other circumstances. I wrote most of the poems in this collection while I was writing the essays. To keep myself open to wonder and joy, these poems enabled me to tap into the natural beauty of my environment and to celebrate wildlife. In this regard, the poems provided much-needed light and sustenance. I hope they’ll do the same for readers.

Is there a local poetry collection that excites you? If so, what is it about the poet’s work that speaks to you?

Eric Nelson’s Horse Not Zebra. Affinity is what comes to mind when I think of what draws me to this sterling book. Every poem sings golden, packed with a kind of knowingness that unfolds gently, wisely and innocently all at once. Eric’s attentive eye and ear are heartfelt, we hear the music in all its intensity and hushed tones, we see the physical environment in its devastating beauty and harshness.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve received from a fellow poet about the writing practice?

To always be in a state of writing. Another way of saying this is being attentive and aware of the sounds, sights, smells and textures around us. To taste it all and allow the perception of our senses to digest what comes to and emerges out of us.

Lastly, who are the four poets on your personal Mount Rushmore?

- Robert Hayden — economy of language — packs a punch in so few words.

- Mary Oliver — for being Mary Oliver.

- Okot p’Bitek — Ugandan poet and master of the Song School literary tradition.

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge — for his poetic landscape and imagination, as well as his ability to blend lyrical, epic narrative, and dramatic elements into a memorable convergence.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.