Talk about a big reveal: After hiding behind construction hoardings for three years, the Asheville Art Museum officially reopens on Pack Square on Thursday, Nov. 14.

The updated building, which includes a replacement the entrance lobby of the former Pack Place, is a glass box embracing the 1926 Italian palazzo-style landmark that once housed Pack Library. The museum relocated there in 1976 from a basement in the Thomas Wolfe Auditorium. (In its earliest iteration, local artists showed their work in a house in Montford in 1948.)

The new complements the old, says Hillary Schroeder, a museum curatorial assistant, “in that it takes on some of the rectilinear lines of the Italian palazzo building. The transparency of the glass curtain wall allows the old Pack Library to shine through. With this building so different, you’re able to appreciate both.”

The road to renovation

Transparency is key for Pam Myers, executive director of the museum since 1995. “We wanted the building to be extremely transparent and be a continuation of [Pack Square Park] and this public living room of Asheville,” she told reporters on a May tour of the facility.

It’s been a long journey for Myers and the museum. As the museum’s collection outgrew the Pack Library building, there was a modest expansion in 2000. In 2003, under Phillip C. Broughton, then-chair of the board of trustees, a vision for the current monumental transformation began to take shape.

“The museum had hoped to open its new, state-of-the-art facility to the community in late spring or early summer 2019,” Myers says. “The discovery of significant and serious preexisting conditions with the 1926 Pack Memorial Library portion of the project and the remediation of those conditions dramatically extended the timeline.”

The project was estimated at $24 million. Since construction began two years ago, costs have risen less than 2%, according to museum spokesperson Lindsey Grossman.

Raising funds was the biggest — and longest — challenge for Myers. Public sources, including the city of Asheville, Buncombe County and the Buncombe County Tourism Development Authority, contributed 19%. The remaining 81% came from private, nongovernmental, sources (e.g., foundations, individuals and businesses) from Western North Carolina and across the country.

Now, after 16 years, Myers says what she loves most is “how light, transparent and open the new portion of the museum is” and how “it frames and respects the historic structure.”

In with the new

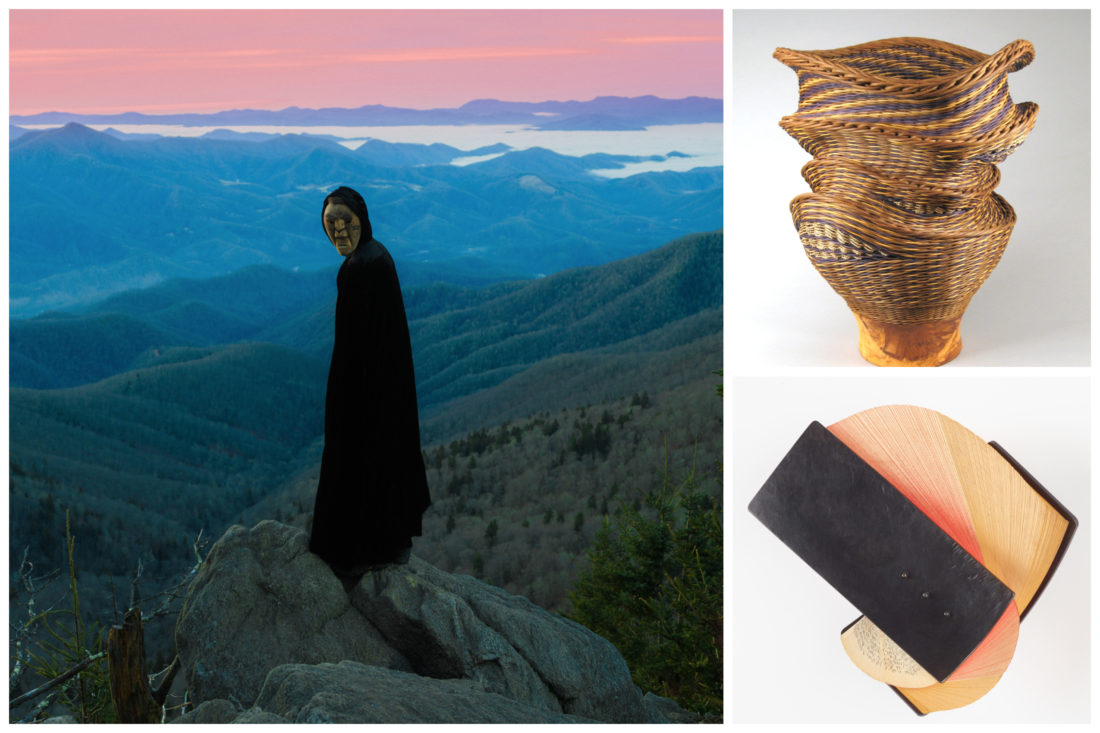

The Asheville Art Museum re-opens with two major exhibitions, Intersections in American Art and Appalachia Now! The first is a selection of some 200 pieces from the museum’s permanent collection, many never seen by visitors. The second is a survey of artists not previously shown at the museum who work in Western North Carolina, Georgia, South Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia.

Appalachia Now! was organized by New York-based scholar and producer Jason Andrew, who manages the estate of Black Mountain College alumnus Jack Tworkov and has curated two Tworkov exhibitions in Asheville.

“Jason specializes in an interdisciplinary approach, which is what the museum envisioned for this particular exhibition,” says Grossman. “His studio visits and critiques provided a new, New York City and international perspective for regional artists.”

Andrew considered more than 700 artists for the exhibition. After visiting many of them in their studios, he chose 50 who work in diverse mediums, from painting to printmaking, poetry to performance, photography to film, weaving and quilting, sculpture and ceramics. “The show celebrates the range of artistic strengths and sensibilities currently at work here,” he says. “It’s a way of juxtaposing the then with the now, to address the rich history of the region through the work of the contemporary artists who call this region their home.”

One such artist new to the area is Lei Han, who creates video installations. A native of China, she has lived here since 2003 and teaches new media at UNC Asheville. “I consider Western North Carolina my home,” she says. “Even though my works are mostly abstract, the beautiful scenery of Appalachia provides not only inspirations for my work but also a place for imagination, contemplation and reflection on my creative process.”

Others, like Wayne Hewell of Gillsville, Ga., and Betty Maney from the Big Cove community in Cherokee, have deep family roots and work in mediums and styles indigenous to the region. Andrew says Hewell makes “some of the most haunting face jugs of his generation.” He calls Maney’s miniature white oak baskets “a unique take on the traditional form.”

For Intersections, a team of scholars, artists and museum professionals from Western North Carolina and around the country started in January 2017 to examine, item by item, the more than 5,000 works the museum owns.

“They were exploring the connections between Western North Carolina, our region, and the rest of the United States,” says Schroeder. Works were grouped in themes about time and place, materials and form, and dialogue and collaboration. “You are often able to find all three themes in a single work,” she notes.

The earliest work is a landscape of WNC, painted around 1860 by Belgian artist William Frerichs, one of the first artists to paint views of the western part of the state. The most recent is “Four Lemons” — a suite of screenprints in enamel ink, made in 2018 — by Donald Sultan, internationally known for semiabstract, close-up portraits of fruit and flowers. An Asheville native, Sultan lives in New York.

Bringing the outside in

Designed by Ennead Architects of New York, the Asheville Art Museum becomes a signature structure at the city’s center. It joins other emblematic buildings in Pack Square and City/County Plaza: the Biltmore Building by world-class architect I.M. Pei, the Neo-Gothic Jackson Building and the iconic City Hall by local architectural legend Douglas D. Ellington.

Visitors will enter the Asheville Art Museum from an outdoor sculpture plaza. Will there be street musicians? “I hope so!” Schroeder says. “We’re going to have benches for people to lounge and eat lunch.”

As they look up through the building’s clear, glass box, passersby and museumgoers will see an inner box, sheathed in a textured metal screen, that appears to float at the upper level. Jutting from the outer wall is a massive vertical rectangle framed with thick zinc blocks. By day, it looks like a window with dark opaque glass reflecting downtown rooftops and the distant rim of mountains to the north.

By night, the transparent building gleams. The metal screen is punctuated with thousands of random piercings that transform into starry constellations. The dark window becomes an illuminated portal, or “oculus,” from the Latin for eye, a metaphorical door into the museum’s SECU Collection Hall housing the permanent collection.

“We’re very excited about the oculus,” says Schroeder. From inside, museumgoers can pause and look out to Pack Square and the vista beyond. “It offers a bit of a reset to all the art you’ve just seen. Everyone can come out here and appreciate the view, appreciate the 2,000-pound piece of glass, appreciate the way the water drips down it when it rains.”

The new museum offers space for better storage, more traveling exhibitions, expanded educational programming and a special area called Art PLAYce, where children and caregivers can participate in self-guided, art-based activities. An art library will be housed in one of the reading rooms of the old Pack Library, recently restored with its original chandeliers.

In keeping with the museum’s theme of bringing the outside in, a rooftop café will overlook a sculpture terrace with panoramic views to the south.

While the building’s modernist glass wall definitely says high-tech, the inside is decidedly high-touch. The architects chose many contrasting materials for tactile pleasure — American ash (native to North Carolina) for floors, ceilings, and some walls; limestone, zinc, terrazzo, polished concrete.

“Wherever you go,” says Lindsey Solomon, the museum’s development and communications associate, “you will be walking on, passing by, perhaps touching wonderful sensory materials.”

Congrats on completing a tremendous civic project. I hope all people in our community benefit – now and future generation!

Ticket prices seem steep. Greenville County Museum of Art is free. Columbia Museum of Art is $10, with reduced prices for students and seniors. (And they used to have free days for visitors from different counties.) Mint Museum in Charlotte has similar charge but reduced prices for students/seniors, with free evenings, 5:00-9:00pm on Wednesdays. High Museum in Atlanta is slightly cheaper.

Will local residents attend with these prices? Will tourists?