Midway through Charles Frazier’s new novel, The Trackers, the story’s narrator and protagonist, Val Welch, cuts himself off midrant, worried that his diatribe against America’s political corruption and class warfare may have overwhelmed his audience of one — Raúl, a young, first-generation Cuban American cabdriver who dreams of going to school and improving his life.

“Part of me wanted to press on,” Val tells readers, “to set him straight about his land of dreams, but the other part of me decided against it. After all, the nation’s big, beautiful strength had always been dreaming forward against the brutal, ugly undertow of reality, the violence in the heart of the human animal, the gluttony and greed.”

What Val leaves unsaid captures a core tension in Frazier’s latest work. Set in 1937, The Trackers follows Val, a Tennessee-born artist, who lands a mural project in Dawes, Wyo., through the Work Progress Administration. Val’s plans change, however, once he is drawn into the inner circle of wealthy, aspiring politician John Long and his wife, Eve, a former singer with a complicated and dark past.

When Eve leaves her husband, absconding with one of his most prized paintings, Val is hired to track her down. In his pursuit, the artist-turned-amateur-private-eye takes readers across Depression-era America, revealing the unrelenting clash between the country’s professed ideals and its less-than-forgiving citizens and landscapes.

Turbulence ahead

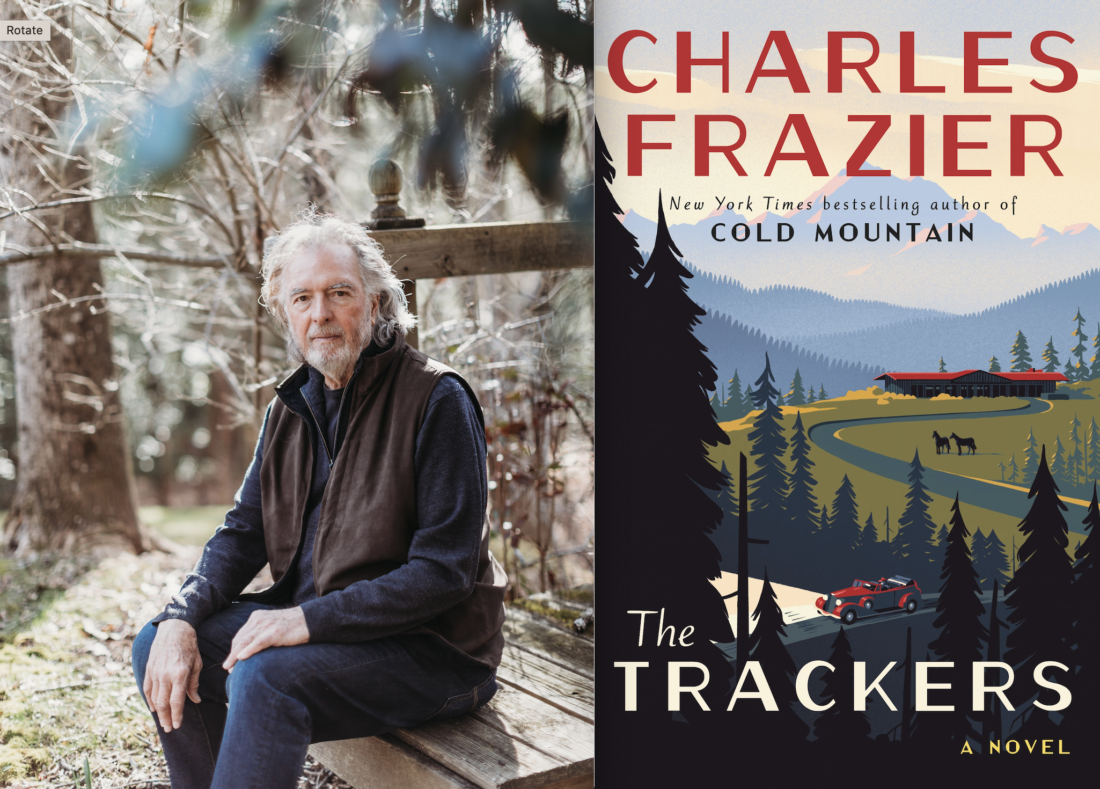

Fans of Frazier’s previous novels — Cold Mountain (1997), Thirteen Moons (2006) and Varina (2018) in particular — will recognize a common thread that connects these earlier works with his latest publication: travel.

Granted, in his prior three books (all set in the 19th century), his characters moved about predominantly by horseback or foot. In The Trackers, Val is traversing the nation by car and plane. The latter, Frazier tells Xpress, was particularly interesting to research.

“Early commercial airlines wouldn’t get much above 8,000 feet,” he says. “So, they’d go through every bit of weather.” Basins beneath seats, he continues, were common features because “everybody was throwing up.”

Not surprisingly, Frazier’s research extended well beyond air travel, as he pored over the period’s popular culture, political tensions, economic woes and makeshift homes.

“Usually, the first couple of years of writing a book is probably two-thirds research and one-third writing,” he explains. “Then it kind of reverses itself by the last year or two.”

But unlike his earlier works, The Trackers was not a story he initially set out to write. In fact, Frazier says, he kind of stumbled upon it by chance.

Once upon a time in Boone

The timeline itself is a bit hazy, Frazier notes. About a decade ago, he and his wife, Katherine, were visiting Boone for a horse show. (Katherine is a longtime rider.)

“I wasn’t really looking for a book idea,” Frazier explains. “I was just killing time, walking around.”

Eventually, the award-winning author ambled over to the town’s post office, where a WPA mural awaited. Triggered by the visual — and with several days before the horse show concluded — Frazier visited his alma mater, Appalachian State University, to peruse its archives. While there, he stumbled upon an image of two WPA artists stationed somewhere out west, standing atop a scaffold and posing alongside a man and woman in more formal attire.

The photograph stuck with Frazier. What was the dynamic between these people? What story did they have to tell? And what did their experiences say about the turbulent period of American history that they were living through?

Despite these initial inquiries, Frazier did not immediately begin crafting a story to satisfy his curiosities. Instead, he wrote and published Varina — a work of historical fiction based on Varina Davis, wife of Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

But by the fall of 2019, he returned to these earlier questions. By then, Frazier says, he was ready to head west to begin research and gain further insight into the characters he was preparing to create. A massive trip was planned for the summer of 2020. Then, COVID-19 arrived, putting all travel on hold.

Welcome to Hooverville

Though Frazier is far from a fantasy writer, one could imagine a scenario wherein a homebound author — accustomed to visiting the locations featured in his latest writing project — might begin fantasizing about travel so much so that he creates additional routes for his main character to take as a means of satisfying his own itch.

Inferred fantasy aside, what becomes apparent when reading The Trackers, and following Val as he zigzags across America, is Frazier’s desire to show the Depression’s impact on as much of the nation as possible.

“I did loads of research on homeless camps around Seattle,” Frazier says, in discussing one of many cities Val visits in his search for Eve.

This research comes out through Val’s narration across several chapters. “The biggest of Seattle’s slums, its Hooverville, had risen out of the mudflats alongside Elliott Bay early on in the Depression,” Val tells readers. He goes on to describe some of the shanties, built of scrap materials held together by used nails and wire. Many of the residents, Val notes, numbered their makeshift homes, believing an established address was essential for being recognized as a citizen. But there were some in the community who refrained, he continues, “on the theory that it would somehow make eviction easier.”

Later in the same chapter, Val is invited inside one of the shanties, shared by a pair of former teachers. Along with armchairs and a wood stove made from a 10-gallon oilcan, the roommates have surrounded the walls with hundreds of books. These works, Val learns, are not intended to display the owners’ former scholarly pursuits but rather function as insulation in winter.

Frazier’s prose shines particularly brightly within these scenes, wherein the novel’s plot is temporarily put aside and he invites readers into the world of the forgotten and overlooked.

As with his previous novels, Frazier says the more he researched the period, the more parallels he discovered with today’s political, economic and social issues — from concerns over housing to the Supreme Court.

“The deeper I got into the research and the more I read, the more it just felt like — ‘My gosh, all of these issues that we’re dealing with right now, they were dealing with back then.’”

‘A heavy drift of grief’

The Trackers also does a masterful job of reminding readers that while the past is prologue, every prologue has its own prologue. This point is most pointedly conveyed through the character Faro — an enigmatic elder and former lawman who in the novel’s present day works for John Long.

“He’s from the last century,” Val tells another character early on in the novel. “People were all strange back then.”

Part of Val’s growth as a character involves shaking loose some of his naivety. And much of his newly gained insights on love, politics and human nature come courtesy of characters such as Faro and Eve.

Along with rich character development, The Trackers also may be Frazier’s funniest book to date. Val’s idealism and beliefs about art as a power for good are often misunderstood by the residents of Dawe or simply met with indifference. Meanwhile, his travels to find Eve and the stolen artwork bring him into contact with of a large cohort of misfits, including a squatting wino and an unruly family living among Florida’s swamp creatures.

The book’s surprising moments of levity, paired with its accelerating pace and endless sense of danger will keep readers continuing to the next chapter. But it’s the power of the story’s parallels to our present day that will likely cause these same readers pause throughout.

In these echoes, Frazier creates a humbling experience. Just as Val initially views Faro as a distant relic of a bygone era, readers are experiencing Val’s narrative from a similar vantage point. In this way, Frazier seems to be simultaneously reassuring us that, as a country, we have gotten through similar past struggles, while also reminding us that the struggles we face today are just the latest in an ongoing saga that will one day leave us all behind.

“Traveling the country, town by town, I felt a heavy drift of grief and sometimes a breakthrough of optimism for the long Depression,” Val reveals to readers early on in the book. “So many lives and ways of life were going or gone and would never return. So much confusion, so much loss of security and faith and wealth, livelihoods wiped away along with fundamental trust in the idea of America and its institutions. Those institutions had been what failed people, the loss of trust in them inevitable. Some days those past few years, I felt a sliver of hope that the country could scrabble its way out of the hole we’d found ourselves in, hope that if we actually tried to make life better for folks who’d been ignored or trampled on for so long, we might even come out better than we’d been before. Other days it felt like too massive an undertaking, that nothing could ever free us of the hard times we’d been living for years.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.