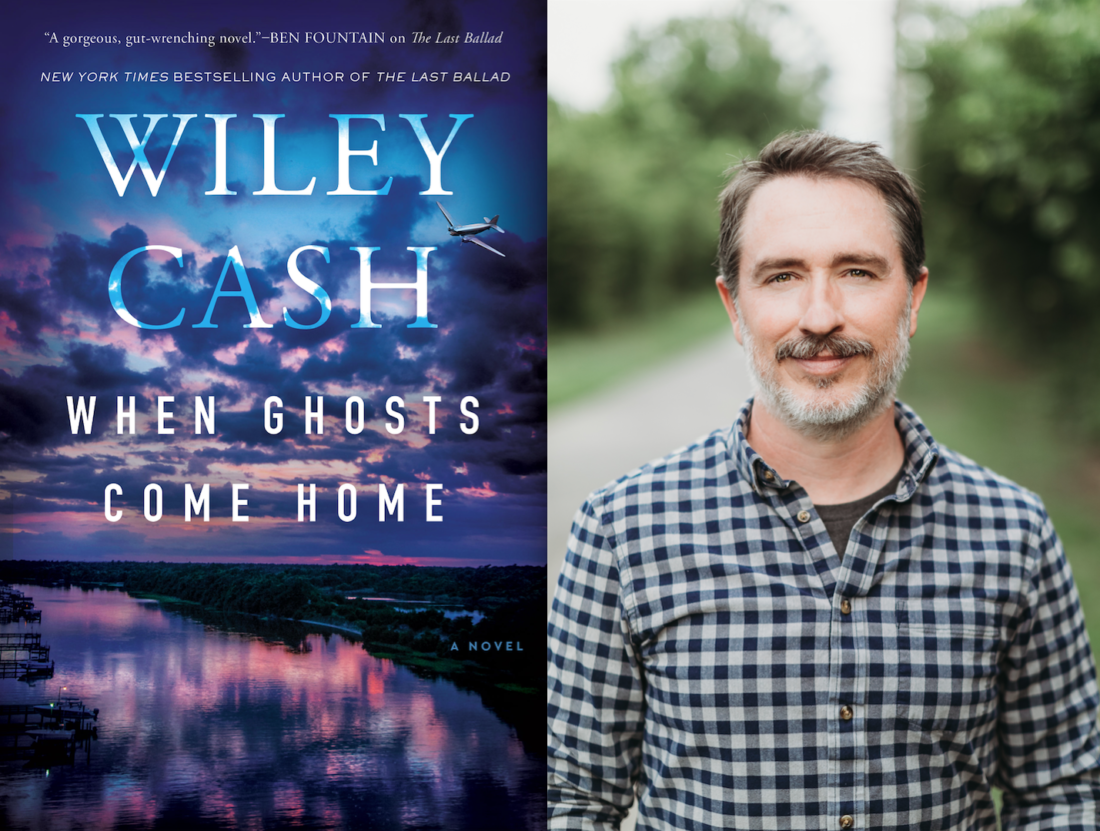

Throughout his career, The New York Times bestselling author and UNC Asheville writer-in-residence Wiley Cash has explored his home state of North Carolina, with a particular focus on the western end. But in his latest novel, When Ghosts Come Home, the author turns eastward to Oak Island, 35 miles south of Wilmington.

“To people who lived there, it felt like a place that had either gone undiscovered or had been forgotten by the rest of the state, that feeling growing so strong as to be nearly palpable as the island changed seasons and a blanket of unperturbed silence settled over it,” Cash writes early in the novel.

The sleepy beach town, however, is shaken when an abandoned Douglas DC-3 airplane, suspected of drug trafficking, is discovered at its airport in the early morning hours of Oct. 30, 1984. Emptied of its cargo prior to police arrival, all that remains is the body of Rodney Bellamy, a local Black electrician and new father.

Rodney’s death is exploited by some in the novel who use the unsolved murder as evidence of Rodney’s complicity in the crime and, by extension, blame all drug-related issues on the town’s Black community. But among those challenging the narrative is longtime sheriff Winston Barnes, who at 63, is days away from facing voters in an election he anticipates losing. His opponent, Bradley Frye, the son and heir of a rich developer, is among the loudest voices promulgating racially motivated rumors on the island.

While a significant portion of the book’s focus is on uncovering the mysteries behind the empty plane and murder, When Ghosts Come Home is far more than a whodunit crime story. Instead, Cash brilliantly combines the pace of a suspense novel with a character-driven literary tale, delivering a large cast of complex characters, all dealing with individual traumas and existential crises amid the cultural and political wars tied to the grounded DC-3.

You can’t go home again

In discussing the impetus for his latest work, Cash says exploring familial bonds was as intriguing to him as identifying Rodney’s murderer or locating the suspected pounds of cocaine unloaded from the plane.

“I wanted to write a book about fathers and daughters,” the author explains. More specifically, “I wanted to write a book about a father trying to understand his daughter.”

Enter Colleen Banks, the sheriff’s 26-year-old daughter, who returns home unannounced by way of Dallas following the loss of her newborn son. Part of Colleen’s grief stems from a sense that her husband, Scott, has put the tragedy behind him, preoccupied with his new position as assistant U.S. attorney. Compounding the issue is the fact that Colleen postponed her own promising law career in anticipation of their growing family.

But it’s the loss itself, above all else, that continues to haunt Colleen as she flees Texas for the coast of North Carolina.

“I can still feel him,” she tells her husband during a long-distance phone call.

Misunderstanding his wife, Scott reassures Colleen that he, too, continues to sense their son’s presence.

Frustrated, Colleen responds: “But I mean inside me, Scott. I can still feel where he was inside me. And now he’s not there, and he’s not here, and I don’t know where he is.”

Returning home, however, does not ease Colleen’s grief — though readers will be glad she did. The unplanned family reunion is where Cash creates some of the book’s most amusing and poignant moments. Cultural and generational differences impede many of Colleen’s interactions with both her father and ailing mother. But there are quiet instances sprinkled throughout the book where the family breaks through these barriers and finds deep, albeit brief, moments of true connection.

The pressure of place

Along with the novel’s familial components, Cash offers an unflinching look at race and racism throughout When Ghosts Come Home.

“So much was implied,” says the author, discussing his own youth in Gastonia in the 1980s. “If you were white, you were Republican. If you were Republican, you were Christian. If you were Christian, you were Baptist. If you were Baptist, you were conservative.

“All these cultural, racial and political attitudes were just so baked into my upbringing,” he continues. “To even question them for a moment was to question all these other identities.”

These personal experiences informed much of Cash’s writing, as did local history. The author, who divides his time between Wilmington and Asheville, notes that residual racial angst remains in Eastern North Carolina. He points to the 1898 Wilmington massacre, a deadly coup led by white supremacists that was largely ignored in history books.

“And then there’s the Wilmington 10,” Cash continues, which involved the 1971 wrongful conviction of 10 civil rights youth activists, nine of whom were Black. All served nearly a decade in jail. In December 1980, the U.S. 4th Circuit Court of Appeals overturned their convictions.

While neither incident is explicitly addressed in When Ghosts Come Home, the lingering consequences of such atrocities factor into the overall story, as Winston must navigate escalating tensions — both within the community and his own sheriff’s department — throughout the investigation.

“I wanted to really write a novel about the place where I’m living,” Cash explains, “to understand it and to see it on a historic continuum. I’m always interested in the pressure of place and how it comes to bear on the contemporary moment.”

In When Ghosts Come Home, Cash achieves this ambitious goal — and so much more.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.