Just before the credits roll on the 1969 counterculture classic Easy Rider, the film’s two longhaired protagonists meet death on their motorcycles, ripped from their rides by a redneck’s shotgun. The haunting ending, while fictional, emblematized some of the most visceral divides in Vietnam War-era America and hinted at a spate of actual so-called “hippie killings.”

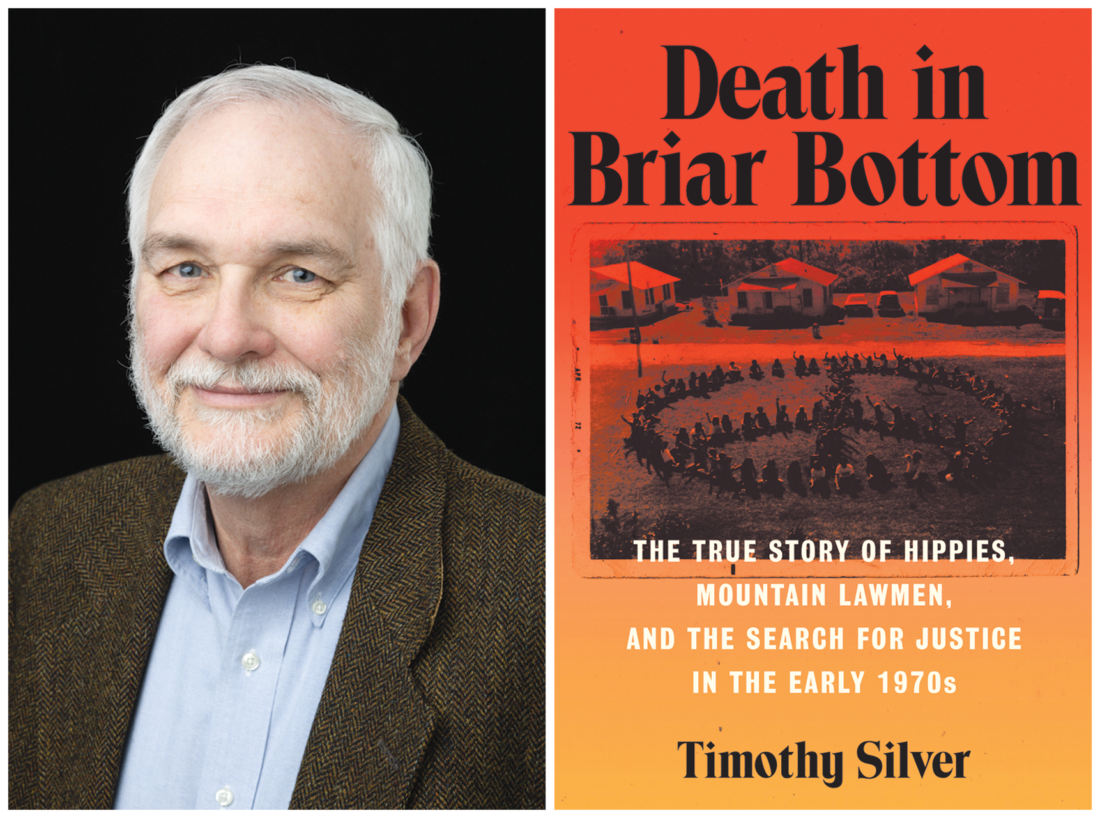

One of those killings occurred at a remote Yancey County campground in the summer of 1972. Timothy Silver, professor emeritus of history at Appalachian State University, gives the case its first full airing in his new book, Death in Briar Bottom: The True Story of Hippies, Mountain Lawmen, and the Search for Justice in the Early 1970s.

It is a gripping investigative history, one driven by Silver’s decadeslong pursuit of the story, which he first encountered contemporaneously as a teenager. He will read from it at two free events: at Malaprop’s Bookstore/Cafe in Asheville on Sunday, Nov. 17, at 5 p.m. (preregister online), and at City Lights Bookstore in Sylva on Monday, Nov. 18, at 6 p.m.

Setting the stage

On the night of July 3, 1972, 24 young people from Clearwater, Fla., parked their vans and pitched their tents at Briar Bottom, a U.S. Forest Service campground in the shadow of Mount Mitchell. They were overnighting en route to their highly anticipated destination: a Charlotte concert by the Rolling Stones, who had just released their epic album Exile on Main Street. The tired travelers played some tunes and sipped some beers before calling it a night.

“We believed we could find someplace off in the mountains and just do our thing,” one of the campers recalled to Silver, but local authorities believed otherwise.

Shortly before midnight, seven heavily armed, plainclothes law officers burst from the darkness and raided the site. Within seconds, a shotgun blast tore the life out of Stanley Altland, a 20-year-old from Clearwater.

Neither Altland, an avid cyclist who managed a health food co-op, nor any of his friends were looking for trouble, and later investigations would establish that they’d brought none to the mountains (save perhaps a little rock and roll and marijuana). But unbeknownst to them, reports (and rumors) of riotous hippies invading local campsites had started to spread in Yancey, setting the stage for the deadly raid.

Historical justice

Who killed Altland? According to the Florida witnesses, the shooter was the man they would later identify as Yancey County Sheriff Kermit Banks, who, they said, appeared to fire into Altland accidentally while striking a different camper with the butt of his shotgun. The campers accused the sheriff and his posse of misconduct from the start of the incident and said it continued after Altland perished.

As for Banks and the other lawmen, their stories changed over time, with one of Banks’ deputies ultimately claiming responsibility for discharging the weapon. In any case, no one was charged in Altland’s death.

Silver re-creates the crime scene and the tragedy with vivid, thorough detail, revealing the cultural forces, personalities, interactions and twists of fate that collided that night. Then, he chronicles the lengthy struggle for justice subsequently waged by the campers, all of whom were arrested that evening.

Many faced trumped-up charges and alleged they were mistreated during the raid and their detention in the county jail. They fought an insular local justice system that seemed predisposed against them at every turn and lawmen who closed ranks to concoct a cover story. But their lawsuits attracted some of North Carolina’s most accomplished civil rights attorneys and widespread press coverage.

The campers’ legal maneuvers ultimately failed to produce justice for Altland and the other victims, but Silver has provided an important contribution of historical justice in this extensive and probing account. He writes that he was surprised to find that his subjects — ’70s hippies who “were about as white as they could be” — had much in common with the victims of police brutality who sparked the recent Black Lives Matter movement.

In the end, Silver writes, the Clearwater campers “got a hard lesson in the selective application of American justice, something countless other marginalized citizens encounter every day.”

Cannot wait to read the Timothy Silver book. Maybe he will research and write a book on murder of W G Morgan (Bill Morgan) of Lenoir, Caldwell County.

Read the book! Great and in-depth research. A lot of the basic setting of the book was centered around my teenage playground. That allowed for more understanding and appreciation than someone not from the area. The book revealed a lot of information I did not know. Really good details. Thanks for a tremendous effort. Will be a history book for a long time. I plan to read again in about 6 months. Just finished Clyde Edgerton’s “Walking Across Egypt”, Both books set in same time frame within same cultural backdrop. Really gives thought to the diversity of people and how we view each other.