Instant Photography: 2003-2014

It’s hard to believe that Polaroid film could completely disappear. There always seems to be someone willing to step in and provide a financial crutch, or two for that matter. (I’ve personally lost count of how many resuscitations the company has had since debuting its instant self-developing film in 1947.) But whatever that future or eventual fate may be, Polaroids will always share in the pantheon of photographic history because of exhibitions like Instant Photography: 2003-2014, a photographic cannonade by Asheville artist Adam Void, opening this Friday, June 6, at Castell Photography.

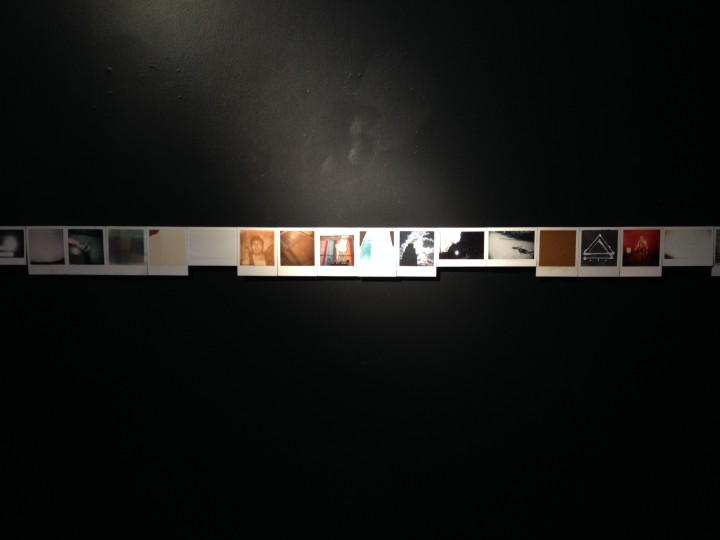

The exhibition features 777 individual photographs — all Polaroids. Except for one vertically-stacked outcropping, they’re all hung in a single, unbroken chain that wraps around the gallery’s two floors of inky black walls. The collection was narrowed down from over 1,600 pieces, each taken or, in a few cases, found by Void between 2003 and the weeks leading up to this show.

Freight trains and train hoppers, bridges, roadsigns and years of photo-documenting graffiti are among Void’s subjects. There are also quick shots of friends, expectant family, houseplants and city landscapes.

A small assortment of hand-painted signs and decades-old marquees dot the walls. One of those reads “Wham, Bam Country Ham” in loose, slightly uneven red and yellow craft paint. A highway-side motel sign has a dangling “O” while a 1960s-era royal blue cross hangs from the barely-seen corner of the 16th Street Baptist Church in another. It juts out into a clear blue Birmingham sky. Such signage, timeless and preserved as it is, rests beside crumbling buildings and roadways that create a vast and largely dilapidated image of the American South, where most of these photos were taken.

Void’s persistent attention to such desolated neglected spaces and urban and social decay crafts, at times, an image of a broken wasteland. It’s most often a physical depiction: cracked and empty swimming pools, overgrown parking lots, broken windows and abandoned cars. They’re among the piles of refuse that Void has made into objects-turned-art and regional documents, if not transient icons.

Some images harbor an expeditious spontaneity that’s embraceable in the Polaroid format. Some are almost too quick to capture, which is to say they’ve been blurred by a rapidly turned head or camera on the move. A few are underdeveloped, others are overdeveloped or not developed at all. Still others are drawn and scratched on with pens, white out and markers. Many, if not most, have also fallen victim to Polaroid’s inherent and somewhat expected light sensitivity. They’ve faded into an ambiguous, mustardy-yellow and beige late-1970s haze.

Void’s taken full advantage of both the film’s sensitivity and it’s accessibility. He refers to photography, and specifically the Polaroid, as the “everyman’s medium” — as everyone can document and create art, with or without photographic training. But by no means is this a slight. Rather, it’s an homage — just as instant photography is an homage to both a medium and the artist.

Instant Photography: 2003-2014 opens at Castell Photography in Wilson Alley on Friday, June 6, 6-8 p.m.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.