One of the largest collections of locally commissioned art in Western North Carolina isn’t housed in a museum or gallery. Instead, it can be found throughout the public areas, waiting rooms and patient rooms of the new, 12-story Mission Hospital for Advanced Medicine.

“A lot of the pieces really speak to the community itself,” says artist and art therapist Becca Allen, whose landscape painting “Calling Me Home” hangs in the intensive care unit waiting room. “One of the things I was thinking of when I was working on my piece was just a reminder that there’s life outside these walls. Especially in critical care, you’re here so long that it becomes normal. It’s nice to have a reminder of what lies beyond the hospital.”

More than 150 local artists contributed 659 works to the hospital’s North Tower; the cost of artwork was just over $750,000. The initial call, issued in August 2018, asked for submission of 2D and 3D works “with an emphasis on nature and/or culture-inspired art,” according to the press release. “Art provides a positive diversion, inspires hope and contributes to an atmosphere of healing and restoration. In the hospital setting, art addresses the health of the human body and spirit, reminding us of the human connections, life experiences and memories that can support and comfort us as we confront illness.”

Comfort takes on many forms, including encouragement. Among those whose work hangs in the collection is Christy Vonderlack, a legally blind abstract artist who not only had two paintings commissioned by Mission Hospital in 2019 but also had two prints installed in Salon SCK in New York City and is featured in this month’s British Vogue. “I may not be able to drive or read anymore, but I can paint some kick-ass abstract,” she said by email. “I’m lucky that so many people find my story inspirational and it makes them want to do their own art.”

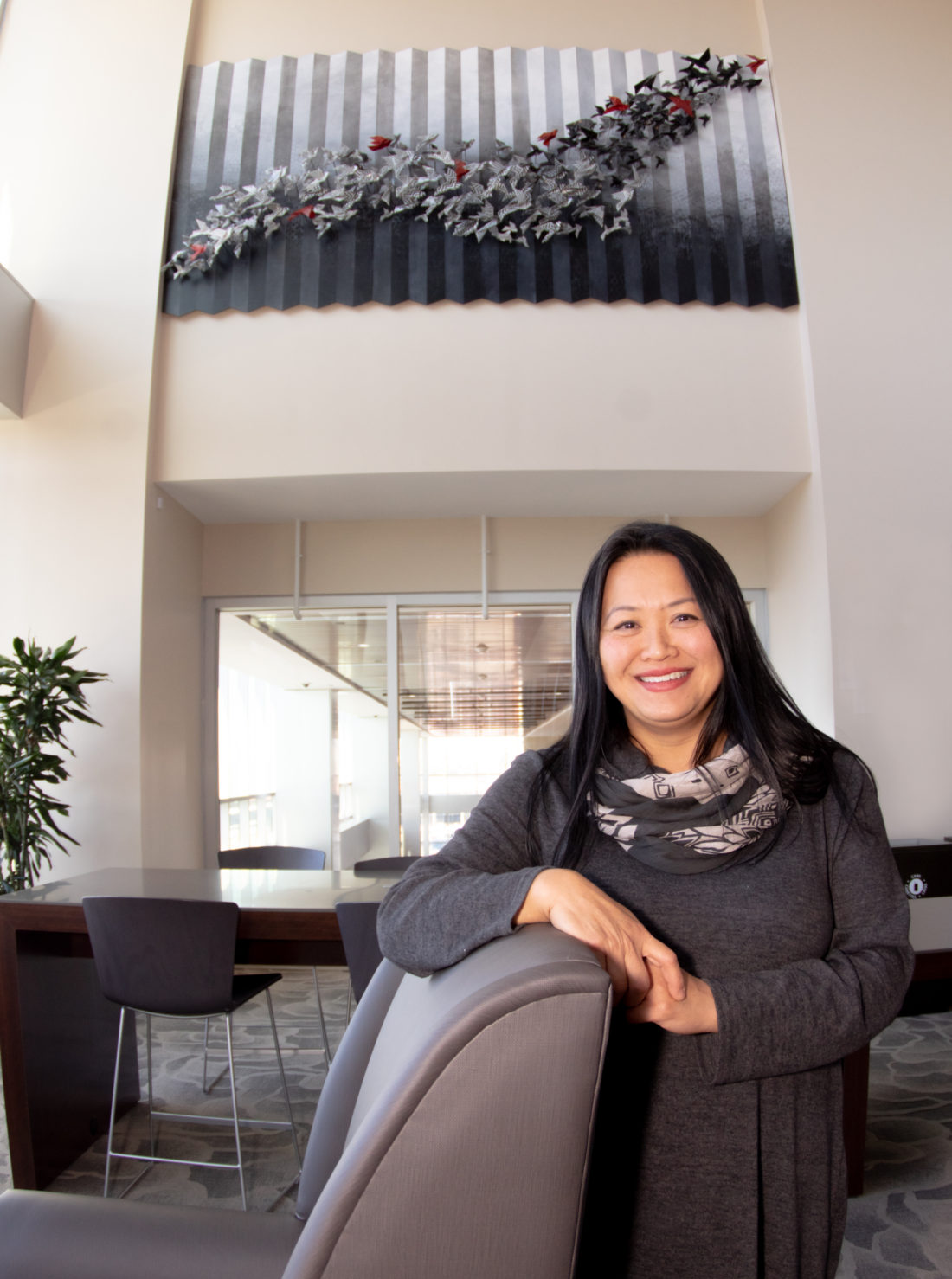

Another artist with a heartening story, and a close connection to the hospital, is Lara Nguyen. In July 2018, the maker and Warren Wilson College professor was a patient at Mission with Stage 1 uterine cancer. She had already agreed to collaborate with fellow mural artist Ian Wilkinson on a wall of the Mission Cancer Center parking deck and redrew the design from her hospital bed. “I told him I was going to do it. I had another mural I needed to do in Grand Rapids, Mich., in August,” she says. “I got my stitches out and I was on a scissor lift 12 days later.”

“Five Forward,” the mural Nguyen completed with Wilkinson and other members of Asheville’s Burners and BBQ collective at the cancer center, has five paper cranes for the five years during which Nguyen will be closely scanned for a recurrence of her illness. “My-gra-tion,” Her large-scale piece in the North Tower also incorporates the origami bird imagery.

“This piece has to do with her mom’s immigration to the United States,” explains Nancy Lindell, public and media relations manager for Mission Health. The intentionally misspelled title is in honor of the artist’s mother, My Thi Nguyen, and the piece itself invokes the children’s novel Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes. That story, about young girl who sets out to fold the titular number of origami birds in a magical bid to overcome leukemia caused by the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, has come to represent a desire for world peace.

“I have always loved / an underdog story,” Nguyen writes in the poem that accompanies her piece. There’s also text in the canvas that’s intentionally hidden in the work, which relates to another installation, called “Murmuration,” that Nguyen created for The Bascom Center for the Visual Arts in Highlands. But because “My-gra-tion” lives in a hospital, its materials needed to be nonporous, so Nguyen dipped the paper birds in resin “and they’re on dowels, and they’re on a board that’s meant to look a little trompe-l’oeil,” she says. “I wanted to give the illusion of [the birds] being on a folded sheet of paper.”

The piece was originally earmarked for an 8-foot wall in another location of the North Tower, but when exhibition planners decided on a space in the entrance, Nguyen’s contribution was renegotiated and grew three times larger. “I was really happy to make it that way,” she says.

In thinking about his commission for the hospital, Kenn Kotara knew he wanted to focus on a body of water, “Because water has that healing component. … It fits right in with wellness,” he says. The Nantahala River was suggested by a consultant, and “I looked at the shape, and I liked it — I love the way it wound its way through [the landscape] — and then I began my research.”

The piece, which looks like a topographical map at first glance, is copper on wood panels. Patina depicts the river; stippled texture throughout is actually hammered Braille. “You can put your hands on it,” Kotara reveals. “The majority of artwork, when you go into a gallery or museum, you cannot touch it. So this idea is of an other-sensory experience.”

Kotara recently completed a 9- by 8-foot, punched Braille piece for the National Federation of the Blind. In the Mission Health installation, the Braille characters, or cells, make up a list poem. “I started looking at the flora, the fauna, the history and the culture of the river,” he explains. The title of the work, “Land of the Noonday Sun,” is the English translation of the Nantahala’s name; Kotara spent a couple of days at the recreation spot wading in the water, gazing at rock formations and watching fish dart.

“If we could send all of our patients there, what a way to recover,” he muses. For those who can’t get to the river, Kotara brought a representation of it to them.

The artist, who is also chair of the art department at Mars Hill University, hopes anyone who interacts with his art — whether seeing it in a gallery or purchasing it for an office — receives some tranquility. Creating work for a hospital, even though the viewers haven’t come for the art, inspires Kotara similarly. “I see that art does have a healing process, if you [take] the time to sit with it, meditate on it and then allow the work to reside within you,” he says.

Although in art therapy it’s usually the patient making the art, Allen says one of the most exciting aspects of that wellness modality is the insights that are developed from interacting with a painting. “Even if you’re viewing someone else’s [work], you’re placing your subconscious on it and letting the art tell the story,” she says. “It’s interesting how the mind can speak through art. … When you’re dealing with something unfamiliar, like making art, which most people stop doing around age 12, the guard is down.” And from that unshielded place arises the opportunity for healing.

While the collection at Mission Health is still new, having opened in early October, “I did have one comment from a person who had their son here for 32 days at that point, and they were in the ICU waiting room,” says Lindell. “They said they felt comforted by [Allen’s] mountain scene. It gave them something to think about besides their troubles.”

Cute…but does the hospital have high quality medical care, and is it a well designed medical facility? After all, it’s not an art gallery for tourists.

The quality of care and the caring of the staff is very high. The atmosphere of the hospital, including that created by all the art and the brightly lite corridors, is inviting and certainly contributes to the well-being of patients and their families.