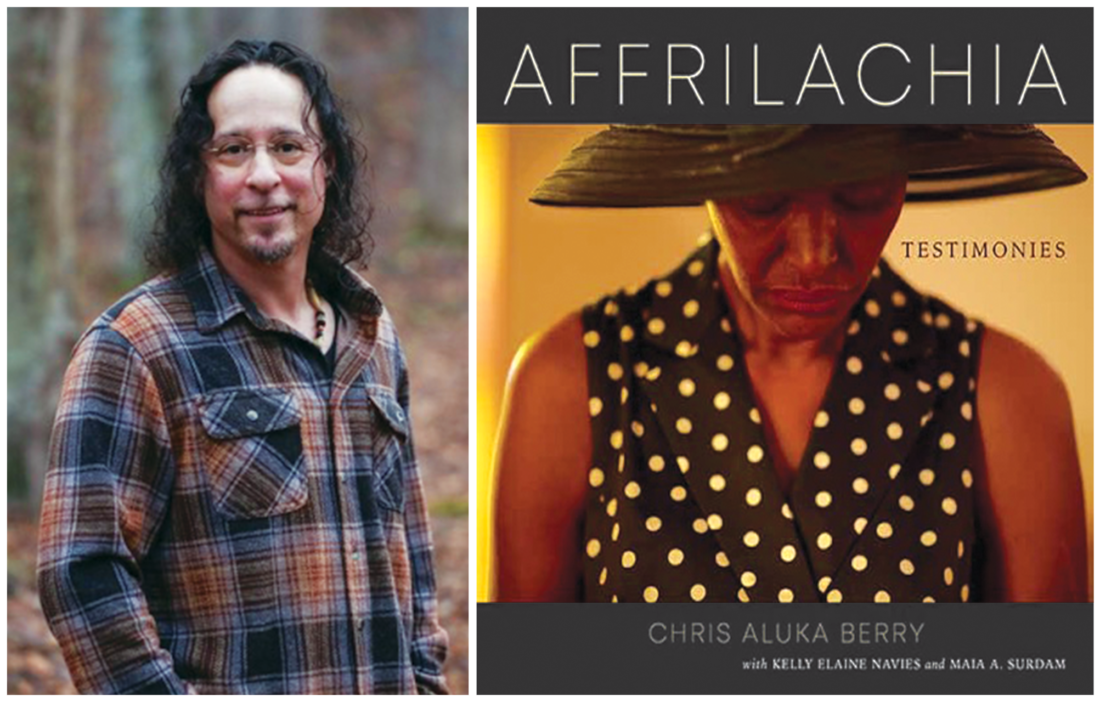

A native of St. Matthews, S.C., Chris Aluka Berry spent many hours hiking and camping in Western North Carolina and other parts of Appalachia growing up.

“But outside of the urban areas like Asheville, I never saw Black folks when I went into the mountains,” says Berry, whose father is Black and mother is white.

So he was surprised when a friend relayed a story that only hinted at the broad spectrum of African American experiences in the region over the centuries. “She had a Black girlfriend whose grandmother was from the north Georgia mountains who would work with different folk remedies, with the plants and different things,” he recalls. “It’s just something I did not know about.”

That conversation spurred Berry, an award-winning freelance photographer, to spend six years visiting Black communities in WNC, northeast Georgia and eastern Tennessee.

“I wasn’t getting paid to do this,” says Berry, who lived outside Atlanta during the six years he was taking the photos. “There were many times I slept in my car or slept at people’s homes. People would call me and invite me to funerals. People would call me and invite me to homecoming events or family gatherings. Every month or two, I was coming up to the mountains.”

The result is Affrilachia: Testimonies, a book of photographs taken at churches, homes, revival services, family gatherings and more. The book also includes oral histories, historic photos and more.

“Affrilachia,” a term coined in 1991 by Kentucky poet Frank X Walker, refers to the cultural contributions of African Americans who live in the region.

Xpress spoke with Berry, who now lives in Marshall, about how the book came together, what communities he visited and why the story of Affrilachia is important.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Xpress: How did you go about finding the communities to write about?

Berry: It was going kind of slow, and then this woman named Marie Cochran, who started the Affrilachian Artist Project, randomly got word that I was trying to document life in the Black communities. She knew folks at Mount Zion AME Church in Cullowhee. She talked to the pastor, asked him if I could come photograph the Easter Sunday service in 2016.

When I showed up that day, very few people attended, and everyone told me, “You’ve got to meet the matriarch, Mae Louise Allen.” I did, and I asked her if I could come back in about a month to do some oral histories and just spend time photographing her life, telling her story, and she said yes. Then I got a phone call about 19 days later that she had passed away. And when I was at the church service, everyone told me, “Oh man, you should have been here 50 years ago. There used to be a thriving Black community here.”

I’m not trying to re-create the past, but I just thought I’ve got to try and preserve these histories while they’re still here. So that really lit a fire under me.

Normally when I went to a new community, I would start at the church. Because in the Black communities, the church historically in the mountains has been a place of refuge. And it’s also like the local community center. I’d always start with the elders and I would interview them.

Tell us a little about the communities you spotlighted.

I focused on three main things in the book. We tell the story of the Rock Springs Camp Meeting in White County, Ga., which has been going on since 1886. We also tell a story in east Tennessee about the Pierce family. And then in North Carolina, we tell the story of Texana [an unincorporated area in Cherokee County].

There was a young girl named Texas McClelland, and the way we understand it through the oral histories and the research that we went through, is that her family was a mixed-race family, Black, Cherokee and Irish. They were living on Cherokee land and were being forced off. We think it was due to racial pressure from the white folks. So Texas and a friend, they scouted a new location for the community to move to. It was this hilltop just outside of Murphy, and it became a pretty self-sufficient community during the Jim Crow era.

Other than Cullowhee and Texana, what WNC communities are in the book?

You have Sylva in Jackson County. There’s a little bit from Waynesville. There used to be a really large Black community in Madison County. I have found some really great historical photographs in Madison County, because the book also includes historical photographs, many of which have never been viewed by the public. These are photos that were hanging on people’s walls or in their photo albums. And there’s a little bit of documentation from the Hillside community in Weaverville.

Why is telling the story of Black people in this region important?

This is something that needs to be preserved. This is a part of history and culture, and I am real big into representation. I’m tired of all the bulls**t of people just representing Black people in the same tired way.

When I started to find out about these Black communities and spend time in them, I was like, “Wow, man, this does not play into any of the stereotypes I’ve ever heard.” This does not play into what a lot of people think of Appalachia, especially if they’ve never been here. They think about the poverty porn, and they think about all of the photos of poor, uneducated white people. Then you start to find out that it’s so much more than that.

This is a time where we need to get past all of this racial stuff and really see each other as people and look past our skin and change those stereotypes. I’m just one little photographer that brought some people together. But the book is a glimpse that can maybe help to change the stereotype of Appalachia.

Berry will discuss the book Wednesday, Feb. 26, 3-4:30 p.m., at Cashiers Community Library and Thursday, Feb. 25, 4-5:30 p.m., at the Madison County Public Library in Marshall. Historian Maia A. Surdam will be at the Marshall event. For more information, go to avl.mx/ejm.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.