To write about nature has always meant to write about humanity’s place in it. The very first clay tablet of the oldest surviving written story, the Epic of Gilgamesh, speaks not only of gazelles eating grass and drinking at a watering hole but of the wild man Enkidu living among the animals and freeing them from a hunter’s snares.

More than 4,000 years later, a fundamental shift in that relationship is redefining the very meaning of the natural world. Greenhouse gas emissions, plastic pollution and nuclear testing have left an indelible global record of humankind’s activity on the earth; indeed, many scientists believe such phenomena signal the start of the next geological epoch: the Anthropocene.

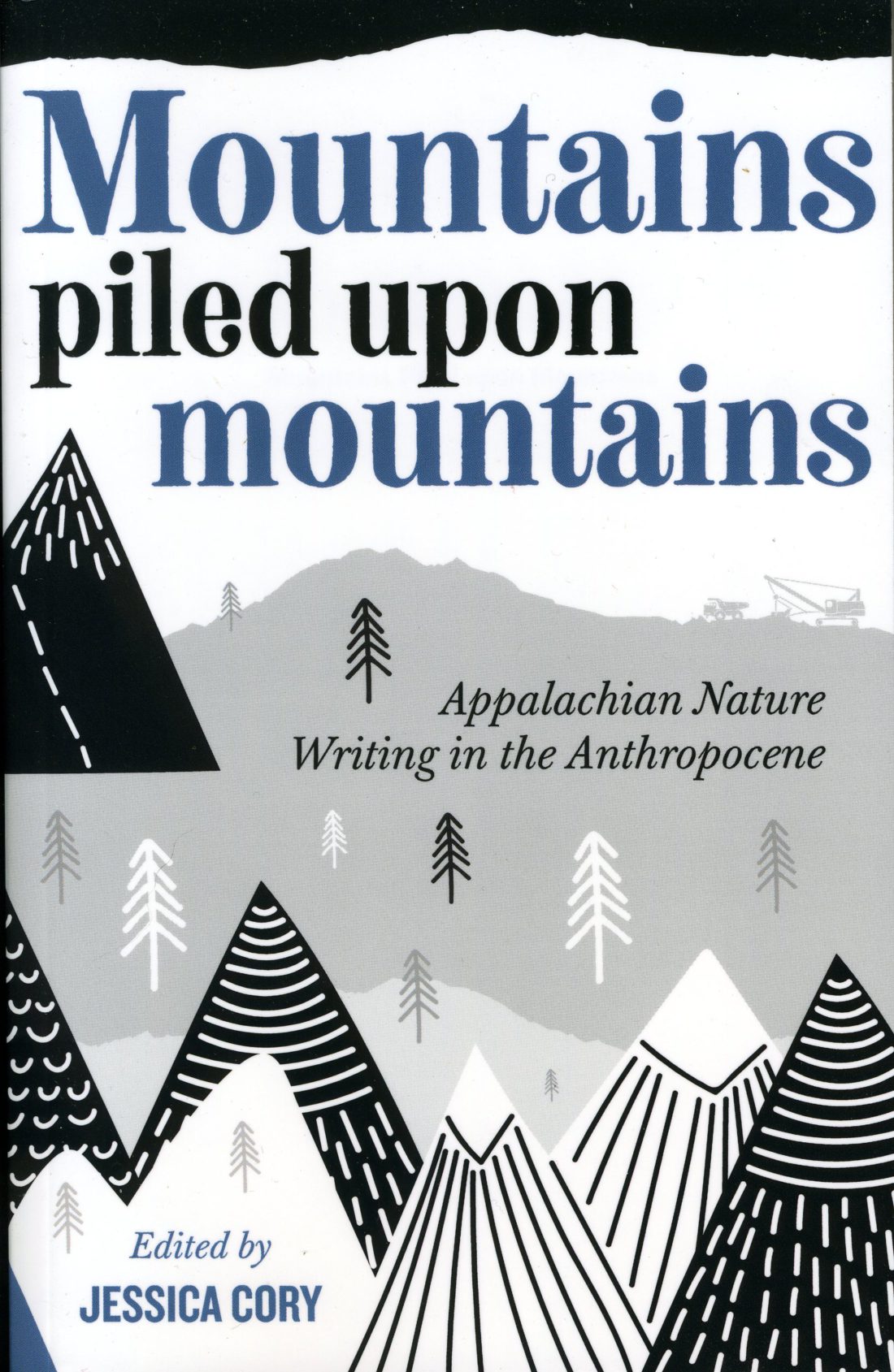

Mountains Piled Upon Mountains: Appalachian Nature Writing in the Anthropocene explores this new reality as it applies to Western North Carolina and the rest of the region. Jessica Cory, who edited the anthology, is a lecturer in the English department at Western Carolina University. She will speak about her work at Malaprop’s Bookstore/Café in downtown Asheville on Thursday, July 25.

The scientific realities of climate breakdown and environmental degradation, says Cory, have caused Appalachia’s literary community to question basic assumptions about this primordial divide. “We have to start looking at what is nature at this point? What is the nonhuman world?” she maintains. “We’ve affected the air, which affects everything else. We’re really getting to the point where we have to look at things a little differently.”

Region at risk

Cory says her focus arose organically as she reviewed the scores of submissions for the anthology. Much of the work touched on the obvious human destruction of the landscape caused by natural gas fracking and mountaintop removal mining for coal, as well as on the growing climate crisis caused by the burning of those fossil fuels.

And while Cory emphasizes that these problems aren’t unique to Appalachia, she says that many writers identify the region “as a sacrifice zone for a lot of the energy conglomerates.” Accordingly, an entire section of the anthology is titled “Destroy.” It includes “Just Before Dawn,” a poem by Kathryn Stripling Byer, the late North Carolina poet laureate, that speaks to the ecological impacts of overdevelopment in the mountains:

“She hears the torrent of oncoming mud / from the neighbors so far uphill / she’s never laid eyes on them,” wrote Byer, who lived in Cullowhee in her later years. “She’d seen the logging trucks clearing / the slope of its timber / the ugly machines come to make way / for dwellings with such pretty names / they sounded like wildflowers / strewn on the hillside around her.”

Mountains Piled Upon Mountains balances that sense of grief with a call for humanity to create a healthier relationship with Appalachia: Other sections are titled “Protect,” “Evolve” and “Celebrate.” Asheville writer Wayne Caldwell’s poem “May Fourteenth,” which appears in the anthology’s “Preserve” section, acknowledges the challenges while maintaining hope in nature’s resilience:

“Redwings is scarce, and when’s / The last time you seen a green snake? / Chestnuts — gone, hemlocks — dyin, / It’s enough to make a strong man cry,” the poet notes. “But still: within a day or two / One side or t’other of the Ides of May / Blinkin yellow flashlights start their twilight glow. / Happened yesterday, right on time, / Though ever year there’s less that come.”

Parts of the whole

The anthology, says Cory, intentionally surveys the broad diversity of Appalachia, with authors based everywhere from New York all the way to Georgia. But writers with ties to WNC are still very well represented: UNC Asheville archivist Gene Hyde, Cowee-based Brent Martin and Asheville native Michael McFee all have work in the collection.

“Despite the fact that it is a book that looks at the entire region, I wanted the authors to be able to give a glimpse into their particular area,” Cory explains. “It provides a very regional look within this macrocosm of the region as a whole.”

Thomas Rain Crowe’s essay “In Praise of Wilderness: Getting What You Give Up,” for example, includes a litany of WNC authors and environmental groups. Crowe, who lives in Little Canada, N.C., says the area’s nature writing is united by a sense of urgency around climate change that lends itself to the anthology’s theme.

“People are thinking, ‘Us humans have really made a mess of things, and it’s all about us: If we don’t correct it, it’s not going to get fixed,’” says Crowe. The term Anthropocene, he says, “is being used by thoughtful people because it does place the blame where it lies. And we need to wake up and acknowledge that and move forward very quickly.”

Crowe also finds a unique spiritual core in WNC’s nature literature that he believes was inspired by the late Thomas Berry, a Catholic priest with a strong environmental focus. The Greensboro native spent much of his retirement writing and teaching in these mountains. Before his death in 2009, Berry advocated for what he called “The Great Work”: transitioning the human presence on the planet from ecologically destructive to mutually beneficial.

“Most of these people either knew Thomas or knew of him and his work,” notes Crowe. “If there is a center post for all of us, it may very well be Thomas Berry.”

Stories to tell

Besides essays and poetry, the anthology also includes numerous works of short fiction. Although Cory admits to feeling most challenged by these pieces — she’s formally trained as a poet and nonfiction writer, not a spinner of tales — she wanted to give readers another point of entry into the Appalachian Anthropocene.

“Not everybody is the weirdo that I am and just reads nonfiction and poetry,” Cory says with a laugh. “I did want to include fiction — even though you don’t think of nature writing as fictional work — because so many people come to the region and come to learn about it through fiction.”

Weaverville native Ellen Perry, who teaches humanities and literature at A-B Tech, represents WNC in this realm. Her piece “Joni and Jesus” uses the region’s seasonal changes as the backdrop for a meditation on aging, in the form of letters exchanged between a fictional sister and brother.

“The whole business with the Anthropocene is humans making an imprint on the land. But my story is about, in Appalachia particularly, the land making an impact on us,” Perry explains. Even a character living in perpetually warm California, she notes, doesn’t want to separate himself from his Appalachian roots and the feeling of fall in the mountains.

Although “Joni and Jesus” doesn’t directly reference humans’ environmental impacts, Perry says the climate crisis and other concerns have colored her creative choices. As an author, she feels increasingly called to base her plots in WNC and give her characters deep histories of interaction with the land.

This approach, she explains, gives her “more of a sense of purpose.” Writing about the region more intentionally “calls attention to the importance of the land and preservation and what it means scientifically, as well as in terms of the human spirit.”

How did Ms. Cory solicit submissions for her anthology? Did she invite the writers to participate?

Cory did invite some of the more well-known authors in the anthology to submit pieces, but there was also an open call for submissions, and much of that unsolicited work did make it into the book. She says she intentionally wanted to include authors with a diversity of experience, from emerging to well-established, in the collection.

Thank you for that information. Very helpful. I appreciate that some new voices were included as well as the more familiar. Were any of the authors people of color or Native Americans?

Yes, a number of the authors were. I didn’t check the whole list (available at https://wvupressonline.com/node/798#2), but PoC/Native contributors included doris diosa davenport and Susan Deer Cloud.

Again, thank you so much. MX writers are so helpful.