If you’re unfamiliar with the story about the Battle of Blair Mountain — the largest labor uprising in American history that resulted in over 1 million rounds fired as well as bombs dropped on Logan County, West Virginia — well, you’re probably not alone.

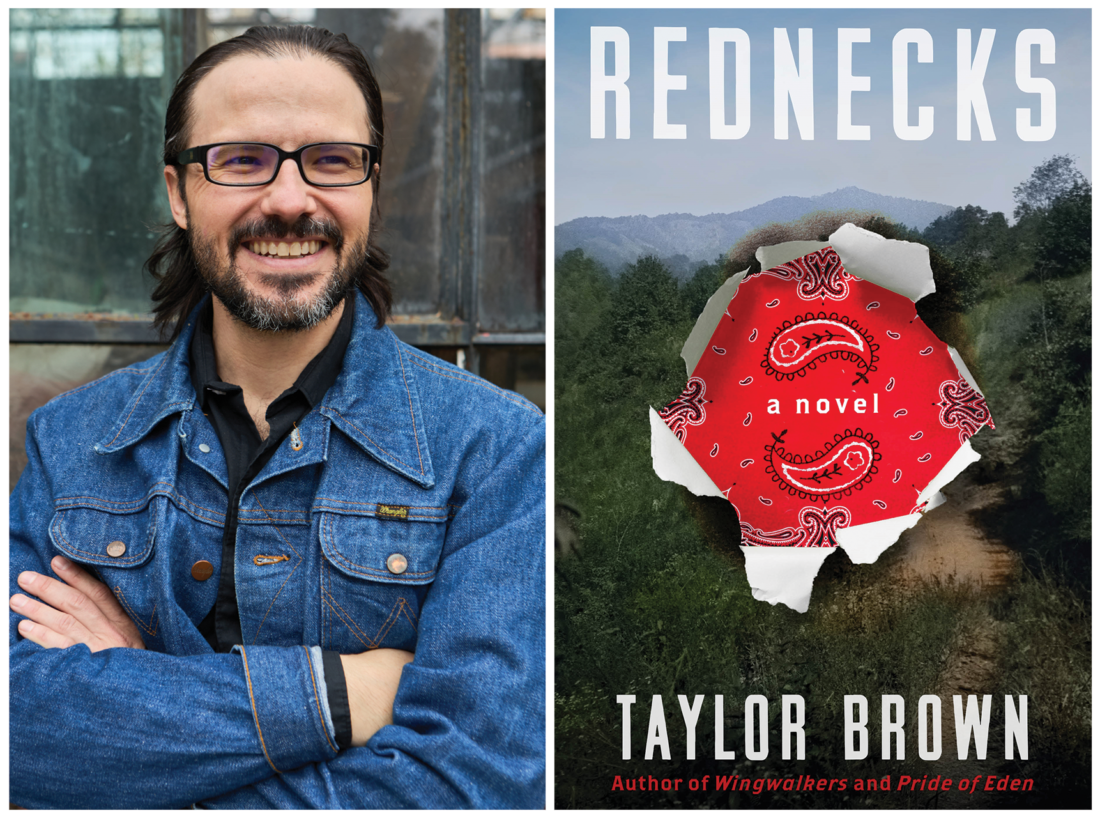

Over the past five years, author Taylor Brown has been researching the topic for his new novel, Rednecks. He says that throughout the process, he shared stories about the conflict with friends, family and fans alike. Typically, no one knew what he was talking about.

Which is fair, the author is quick to note — Brown himself only discovered the story by chance in 2017, when a friend from Logan County happened to mention the battle in casual conversation. That discussion stayed with Brown.

“They are a hundred men at first, then two hundred. Five hundred. One thousand,” the author writers in Rednecks, at the onset of the nearly weeklong battle. “An army of men rising from the earth, clad in blue-bib overalls. They hail from Italy and Poland, the Deep South and Appalachia. One in five is Black. They wear red bandannas knotted around their necks, as if their throats have already been cut.

“People will call them primitives and hillbillies, anarchists and insurrectionists.

“They will call them Rednecks.”

On Thursday, May 23, at 6 p.m., Malaprop’s Bookstore/Cafe will host a hybrid event featuring a conversation between Brown and fellow author Tessa Fontaine. The pair will discuss the battle as well as the author’s desire to introduce readers to this previously forgotten, if not deliberately buried, piece of American history.

‘Blood instead of floodwater’

One of the joys of reading Brown’s latest work of historical fiction is the large cast he creates on the page. While the book’s list of characters edges close to double digits, two of the novel’s central protagonists embody the story’s broader tensions and themes.

Mary Harris “Mother” Jones is one of several historical figures Brown includes in Rednecks. An Irish-born American labor organizer, Jones was once called “The Most Dangerous Woman in America,” the author informs readers early on. Her character, who confronts coal operators and politicians with unwavering moxie, is a megaphone for workers. Her public speeches also provide readers with historical context about the period.

“Now you men who fought in the Great War, you were told it was a war for democracy, were you not?” she asks a crowd of miners early on in the novel. “You saved the world from oppression and came home and found what? More oppression. More autocracy. A new bunch of American kaisers, men who made their fortunes on the war, on coal and steel, arms and machinery, on the blood and muscle of American fighting men, only to abuse those men back here at home, exploiting them in their mines and mills, factories and stockyards and killing floors.”

Whereas Mother Jones is pure political force, the fictitious Dr. Domit “Doc Moo” Muhanna, a Lebanese-American physician inspired by Brown’s own great-grandfather, serves as the novel’s moral compass in an otherwise brutal tale.

Given his profession, he is also one of the book’s few characters able to travel between camps, revealing the deadly cruelty that both sides inflict. And because of his adherence to the Hippocratic oath, as well as his humanitarian lens, his compassion often offers a stark contrast to the violence that surrounds him.

“Sometimes it seems worthless,” he tells one character midway through the book. “All this work and care to stitch people back together, to staunch wounds and set bones and battle infections, and every time I finish one, there are ten more, like holes busting loose in a dam, except it’s blood instead of floodwater.”

“Blood and time,” the other character responds, “those ain’t battles you can win.”

A history of violence

What Brown often conveys through Mother Jones and Doc Moo is the impact that violence has on both the individual and the community. But this violence, Brown emphasizes throughout Rednecks, is not unique to the battle at hand. Many of the book’s characters are recent veterans of World War I. Others have direct links to the Civil War, previously served in the Philippines or exchanged gunfire out west.

“Trauma engenders more trauma,” Brown says, in speaking about the novel’s themes. “When you come from all that violence, it’s easy to get to it again.”

But whereas a less skilled writer might only dwell on the brutality present on battlefields, Brown’s talent is in exploring how political violence infiltrates an entire community.

In one instance, a family outing for ice cream erupts into a physical assault when police officers suspect a citizen of being part of the uprising. In other instances, Brown describes the suffocating nature of occupation.

“People were afraid to go outside; the air was full of death,” he writes. “They’d taken to sleeping in cellars or under beds, their children curled in bathtubs. At night, any light drew a shot.”

The great experiment

Yet, the book never exhausts readers, despite its heavy topics and the large cast of characters to track. In part, Brown succeeds in managing both elements through the story’s structure. Rednecks’ short chapters (some of which are barely a page long), propel readers forward, creating an exhilarating pace.

But it’s also Brown’s language that makes the novel hard to put down. The details he offers are haunting, especially when describing the region’s landscape. Just like the community members who are scarred both emotionally and physically from current and former battles, so too is the land. And so often in the book, the region’s topography is personified.

In one scene, workers dig through “the black veins of West Virginia coal[.]” In another, the writer describes the day’s descending sun and “the shadows growing longer, sharper, the world growing claws.”

But ultimately it’s Doc Moo and his relationship with both the war-torn community and his own family that keeps readers invested. In a world where violence is ubiquitous, the physician gives readers reason for hope, however conflicting his outlook may seem.

“Moo loved America, he did,” Brown writes midway through the novel. “This country had attempted a ‘Great Experiment’ for the promotion of human happiness — a written recognition that all men were created equal, endowed with certain inalienable rights, and the state existed to guarantee those liberties, not to impede them. In practice, those high ideals made it a nation of deep hypocrisy — a country ever on a knife’s edge, ever failing to live up to its own principles. A nation ever in conflict with itself.”

To learn more about the Thursday, May 23, event, visit avl.mx/dot.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.