by Alli Lindenberg, ednc.org

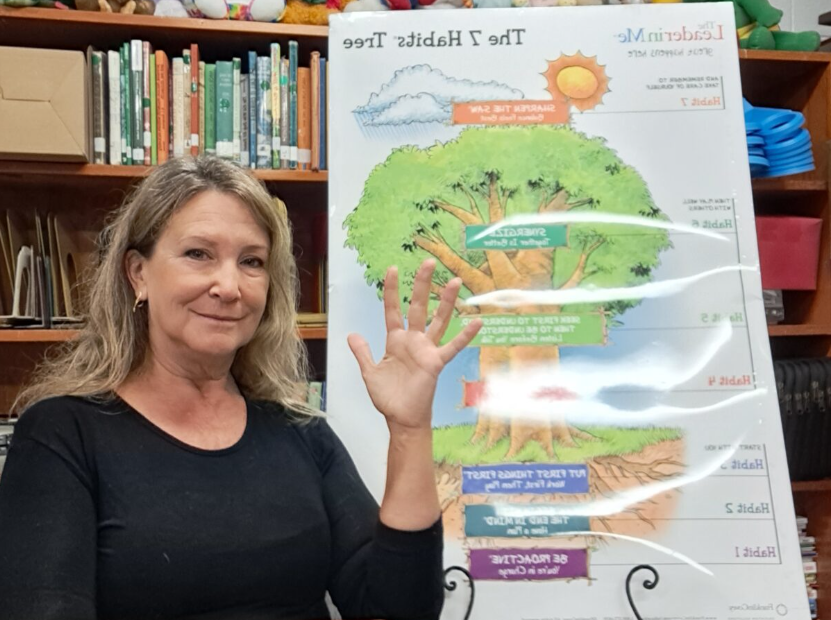

What started out as a curiosity quickly became a passion for sign language interpreter Kim Martin. Over two decades ago, Martin enrolled in a sign language interpreting class at Santa Fe Community College in New Mexico with hopes of learning the language that piqued her interest. Today, she is an award-winning educational sign language interpreter and advocate for deaf and hard-of-hearing students.

Earlier this year, Martin was recognized and presented with an award by N.C. Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. Martin is the lead interpreter for Buncombe County Schools, where she’s worked since 2004, aside from a brief hiatus to work in college interpreting.

“I just fell in love with it and found that education was really kind of my niche. I really like working with kids, especially in our field,” said Martin.

Many of the kids that Martin works with are not only deaf or hard of hearing but also struggle with language deprivation. Language deprivation is when a child is subjected to a lack of full access to language during the critical period of development when language acquisition occurs, typically during a child’s first five years of life. It is estimated that up to 70% of deaf children experience language deprivation, according to the National Association of the Deaf.

“Most deaf kids are born to hearing parents, and there’s usually a lag time of identifying deafness in a baby and often a struggle with accepting that you have a deaf child. There’s a long process in which there can be a lot of language deprivation for children. So for us, that’s a big part of our job, being language role models and teaching,” said Martin.

Martin is part of a larger team made up of an audiologist, two teachers of the deaf, hearing interpreters and a deaf interpreter. Hearing interpreters are interpreters who use hearing to translate language for deaf students. Deaf interpreters are interpreters who are born hard of hearing or deaf. They serve preschool students to seniors in high school. The interpreters typically provide one-on-one support for students throughout the school day. This support extends beyond academic instruction as interpreters provide social support on the playground or in the cafeteria and during extracurricular activities.

This school year, the team started a deaf education playgroup. The playgroup addresses language deprivation by focusing on language acquisition for their youngest students.

“In the past, it’s been the case where they’ll take an interpreter and put them in front of the student and be like, ‘OK, now you have an interpreter,’ but they don’t know the language themselves. It’s very complicated to try to teach someone a language and academics at the same time. You have to learn the language first. That’s what this little playgroup is all about is trying to get these kids language acquisition first, so that then they can learn the academics, but you can’t really do both at the same time,” said Martin.

The team is also working on revitalizing a cluster program that the district used to have where deaf and hard-of-hearing students were bused to the same school, but that program was disbanded about a decade ago, according to Martin.

“We’ve been working really hard to get the cluster back so that the deaf and hard-of-hearing kids can be together. Because, as you can probably imagine, being deaf or hard of hearing is very isolating. When the only person who knows your language is your interpreter, it’s very isolating. It’s really important for the kids to be together so that they can see other deaf people and other people using sign language so they don’t feel so isolated. We’re working on reinvigorating that cluster program right now,” said Martin.

While Martin loves her job, it isn’t without its challenges. Compensation for interpreters is lower in the school system than outside of it. The district struggles to hire long-term employees, and school officials often have to hire contractors to fill the needs they can’t meet with their own staff.

“I think as far as educational interpreters, just the weight of being responsible for teaching someone a language … we’re grossly underpaid. Contract interpreters are paid three times as much as we are,” said Martin.

Martin plans to keep advocating for both more support for her deaf and hard-of-hearing students and better pay for interpreters. With a career spanning over two decades in the field, she hopes her commitment and insights will inspire others to care more about both hard-of-hearing students and their support staff.

“I just have a heart for, you know, these kids. It is my passion, and it’s so important to me that these kids have access to language, to acquiring language and to learning. I do feel like if I wasn’t here, I don’t know who would be doing it, so that keeps me in it,” said Martin.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.