When Asheville Mayor Esther Manheimer visits local elementary schools, wide-eyed little girls sometimes ask: “You’re the mayor? You’re so pretty!”

“I call it the ‘princess mayor effect,’” says Manheimer, laughing. But underneath the humor lurks a more serious issue: Those young girls, she says, “don’t yet know that it’s possible” for them to be running the show. “It’s this thing that’s unattainable.”

And while the number of women in politics has definitely grown over the last few decades, “Politics is still a gendered space,” says Debbie Walsh, director of the Center for American Women and Politics. “Women see these institutions and don’t see a lot of people that look like them in charge, and that may lead to a reluctance to run for office.”

Electing women, says Walsh, “matters for a number of reasons. First, 51 percent of the population is female, but at any level of office, women make up no more than 25 percent of those elected officials. Women are half the population, and they’re not represented in our government.”

Of the 100 biggest U.S. cities, 17 currently have a female mayor, and in cities with populations over 30,000, only 18.4 percent are headed by a woman, according to the New Jersey-based organization, an arm of the Eagleton Institute of Politics at Rutgers University.

“I never thought that I would be mayor,” Manheimer admits. “I thought that’s something only other people are capable of, not me. I used to have this idea in my mind of people who could play these leadership roles. They were generally men, they went to Harvard, they were the most brilliant people on earth, and everyone recognized them as being so. I just remember, one day, realizing that they are people too.”

Politicians, doctors, lawyers — “All of these people are just people,” she says. “This is something you can do because you’re a person too. It just dawned on me that it wasn’t this distant thing: It was achievable for someone like me.”

And though women are still a small minority in U.S. politics, three women have served as Asheville’s mayor during 14 of the last 18 years.

“I think it says that Asheville believes leadership can be in anyone,” notes Terry Bellamy, the city’s first African-American mayor. “And I think it says that our community is open to good leaders, regardless of who they are, as long as that person has a vision and can cast that vision.”

That kind of political track record is significant, says Walsh. “You don’t have many places with that kind of continuity of women leadership. Asheville has a history now of electing women to top executive positions, and that’s not typical of what we see around the country.”

Overcoming mindsets

“Asheville’s always been cutting-edge,” says Manheimer. “We have our first female police chief, and there are very few places in the country that have female police chiefs. I don’t feel like [gender] has even been a factor for people.”

But Bellamy, the second woman to hold Asheville’s top elective office, has a somewhat different memory. “After I won my position as mayor [in 2005], a reporter … called and asked me how I would be able to balance my family life, my work life and my political life. My response to him was, ‘If I was a man, would you have asked me that question?’

Buncombe County Commissioner Holly Jones reports similar experiences. “I’ve been in this 14 years now, and I’ve never observed … males [getting asked], ‘How are you going to balance family and elected service?’ That has been a weird differentiation, you know, because a lot of times the guys also have families. So why is life balance not also a challenge for them?”

Bellamy, meanwhile, says, “People’s mindsets were one of the main things I had to overcome, not because I couldn’t do the job, but the limitations that were placed upon me: I had to make sure I was well-read, well-versed and stronger than anyone else in the room.”

Bellamy says she felt she needed to prove herself to her city and her constituents: “I didn’t want anyone to look at me and think, ‘Oh, she doesn’t know what she’s talking about.’ It challenged me.” But at the same time, she reveals, “It made me feel empowered and just as good as anyone else in this room, and I’m going to prove it!”

Yet there’s more than self-esteem at stake, says Walsh. “Women and men have different life experiences: Our elected officials should represent our perspectives and our needs. And it’s important to have a full range of the experiences that citizens have as part of the conversation.”

A different image

Asheville’s first woman mayor, Leni Sitnick, says she didn’t experience “too much gender prejudice — not from staff and not from the community.”

“Obviously I can’t compare what it’s like to be a man running for mayor,” she says. “But I ran against [Charles Worley], a native Ashevillean, very popular and very well-liked.”

And gender aside, Sitnick was “this different-looking person: I had a head of curly hair, and I wore jeans. My boys had dreadlocks down to their knees and sang in a reggae band. I was dubbed the ‘hippie-granola-Birkenstock candidate.’ We were different.”

Sitnick’s 1997 victory, she says, “was the beginning of the beginning. It was a time when Asheville was really coming into its own.”

These days, she continues, “More and more women are taking positions of leadership in business, industry and politics — and I say, ‘Yea!’ There was a time in this country — the ‘Betty Crocker years,’ they’re called — when women were expected to assume certain roles. The men go to work, and the women stay home and take care of the household.

“That’s all changed,” says Sitnick. “That’s not part of the modern world, and children are exposed to that today. They see women in different roles, and of course that inspires them” to pursue different paths as well. “The more it happens, the more it’s going to happen.”

As mayor, Sitnick took her mentoring role seriously, visiting schools and speaking in auditoriums. “I was always asked what was it like to be mayor, and I would always tell the story of when I was a child,” she recalls. “My parents told me, ‘If you study and you work hard, listen to your teachers and believe in yourself, you could be anything you want to be.’”

And now, “I have young adults come up to me and say, ‘You came to my school when I was in fourth grade, and I remember what you said.’ And they’ll tell me how it inspired them and made them feel confident.”

Getting more women elected

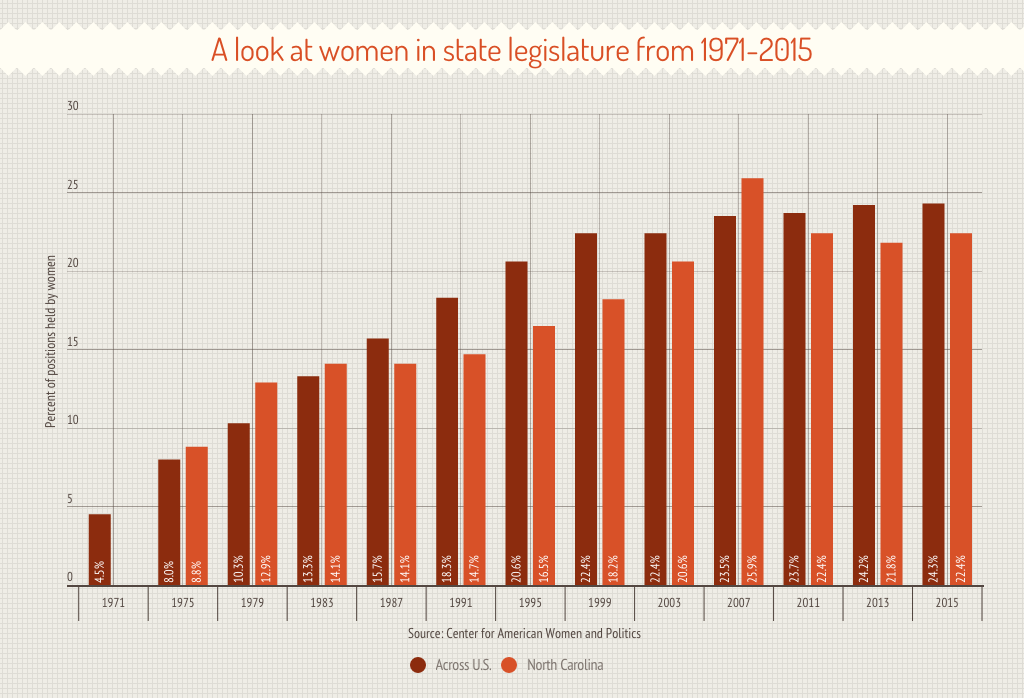

In 1975, a mere 8.8 percent of state legislators in North Carolina were women; today, that figure is 22.4 percent, according to the Center for American Women and Politics. More recently, however, the progress has stalled.

Nationally, says Walsh, “We’ve actually seen kind of a flat line since about 1999 or so. It’s not that women are running and losing: When women run, they win at about the same rate as men do. But we haven’t seen enough of an increase in the number of women running for office.”

In politics, notes Walsh, Democrats are usually more concerned with issues affecting women, children and families. “You’d see it more as a partisan split,” she says. But with women voters, “We’ve found that it cuts across party lines. While Democratic women are most likely to vote for women, Republican women are more likely than both Republican and Democratic men.”

So how do we encourage more women to run?

“The No. 1 reason why people get involved is when people ask them to,” says Jones. “We need to directly encourage talented women right out of the gate: That kind of begins the wheels turning.”

Still, cautions Walsh, “It’s not a simple answer. There’s a lot that goes into that. One of the reasons is that women have more complex lives than men.”

Because women are more likely to be taking care of children, they “tend to run for office when they’re older. And if you don’t start until your 40s or 50s, you may not work yourself up the political ladder.”

Gender differences, notes Walsh, also affect candidates’ reasons for seeking public office. “Women are more likely to say they ran because of a policy issue, while men are more likely to say they have a long-standing interest in politics. Men are much more likely to wake up one morning and say, ‘I would be the best policymaker they’ve ever seen!’”

Another complicating factor, she says, is that women interested in promoting change are more likely to go into nonprofit work than into politics.

Catch-22

Once they’re elected, however, studies have shown that “women are more likely to work across party lines to get something done,” says Walsh, so getting more women involved in politics could help address the current political gridlock. “What we’ve found is that it’s not the impact that women make: It’s the difference they bring to the table.”

But because women tend to be less confrontational than men, “it becomes a bit of a Catch-22: I see this gridlock, and I don’t want to engage in that. But if I don’t run for office, then I won’t see more women who’ll be willing to reach across party lines.’”

Pat Deck, membership chair for the local League of Women Voters chapter, says: “There are a lot of women’s issues that need to be addressed, and who better understands them than women?”

Things like health care, education and sexual harassment, she points out, “are issues that affect young women, and I think women representatives understand that. The decisions that are made for us are made by men, usually, and they don’t get it sometimes. I don’t mean to be flippant, but they really don’t.”

Traditional gender roles create additional challenges, says Manheimer. “You can talk about women’s liberation all day long, but if you’re a wife or have children, it’s still very hard to overcome the traditional allocation of tasks. … I have many friends who work full time, and I cannot tell you how many times, over glasses of wine, it’s like, ‘Yes, we handle all the child care. I’m the one that monitors the homework and picks up groceries.’ I’m not saying there aren’t men out there that do these things, but the traditional role, no matter how liberated you are, is always going to be there.”

The key to increasing women’s representation, says Deck, is “talking to young women about taking on a role in public service, helping ensure equal access to jobs, to education.” Not so long, ago, she notes, women were “fighting for the right to vote. I think we have to honor that and encourage people to be involved — and not just involved, but actively involved.”

But getting involved in politics, notes Manheimer, “requires time and attention. … I have so many friends that are smart and capable, but they can’t or don’t want to situate their lives in a way that dedicates that much time to something like that.” Government leadership “is an incredible burden — of joy,” she adds, correcting herself with a laugh. “An incredible burden of joy.”

Great article, Hayley!

http://postimg.org/image/vxckxb8zx/

Maybe if women stopped harping just about women and made it about everyone…

We have some wonderful women at the state level, why were they not included in this article? Elizabeth Dole for one, Kay Hagan, Patsy Keever is Chair of the Democratic Party.