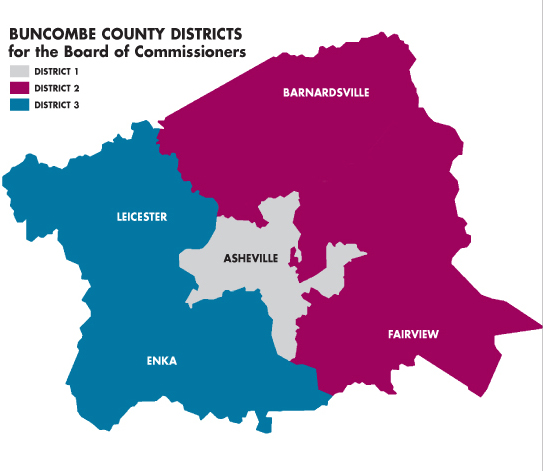

Four candidates are battling for two seats on the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners. In each case, these contenders hold vastly different views on a range of issues, from taxes and spending to growing the economy and protecting the environment. Also at stake is which party holds a voting majority on the board. Here’s a closer look at those races.

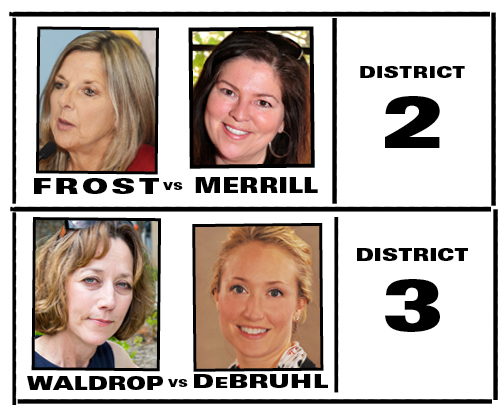

District 2

Republican Christina Merrill has logged a lengthy list of criticisms of Democrat Ellen Frost since losing to her in the 2012 election by a mere 18 votes. After mounting an unsuccessful legal challenge (see the “Ballot Brouhaha” sidebar), Merrill opted to oppose the incumbent in a rematch this year.

Their previous faceoff gave Democrats a 4-3 majority on the board, and this year’s race could have the same impact, potentially steering county government in two very different directions. Both candidates are vying to represent District 2, which encompasses Black Mountain, Fairview and Weaverville and is nearly evenly divided between registered Democratic and Republican voters.

Merrill, a Fairview resident who owns a small marketing business, wants the county to focus on cutting spending. One of Frost’s most egregious moves, her opponent maintains, was her 2013 vote in favor of a budget that increased the property tax rate while giving the commissioners a 1.7 percent pay raise.

“I don’t look at Buncombe County as a big corporation and worry about Buncombe County’s bottom line,” says Merrill. “I worry about the taxpayer’s bottom line and my neighbor’s bottom line.”

In 2013 Frost and all of her colleagues except Republican Mike Fryar voted to approve a budget that raised the tax rate from 52.5 cents to 60.4 cents per $100 of property value. “I don’t like tax increases anymore than anyone, but it was the responsible thing we had to do,” says Frost, arguing that unusual circumstances made the move necessary.

That year, Buncombe County reappraised property values for the first time since 2006 and the subsequent real estate crash. The revaluation, conducted by the county’s Tax Department, slashed total property value by a whopping $2.8 billion. So even though the rate increased, residents whose property dropped in value didn’t necessarily have to pay more to the tax collector, notes Frost.

Merely to generate the same amount of revenue as before, the county would have had to raise the rate to 57.83 cents. The remainder of the increase was mostly to cover unfunded state and federal mandates, she says.

As for the pay raise, Frost calls it a “cost-of-living increase” that benefited all county employees — and, for her, “amounted to $8 a week.” Serving as a commissioner, she maintains, is “more than a full-time job, and I think we need to be careful. If we make the salary nonexistent, we’re probably going to end up with folks who are retired or wealthy.”

Merrill, however, says the county could have kept the tax rate down by cutting spending. “I would’ve found ways to reduce the budget so we would not have to raise taxes,” she asserts. Asked specifically what she would cut if elected, she points to “excess” money given to nonprofits that the county contracts with to provide services beyond what is mandated.

This year, on a 5-2 vote, Frost joined the majority of commissioners in approving $2.3 million worth of community funding grants to a wide range of organizations, up from last year’s $1.88 million but decidedly less than the nearly $4 million requested. The funding, argues Frost, provides a good return to the community while representing less than 1 percent of the county’s nearly $337 million budget.

About 83 percent of that money, notes Frost, funds “core services”: health and human services, education and public safety. Merrill, though, says that’s not enough. She wants “to put our core services back on top of the priority list,” charging that her opponent has “gone off on a tangent of personal projects.”

One example Merrill mentions is Frost’s vote to award $80,000 to Moogfest, a private festival in Asheville held back in April. The county funding was part of its economic incentive program. But, argues Merrill, “If our classrooms are falling short, in my opinion that money should go to the classrooms.”

Frost, meanwhile, cites a report by the Economic Development Coalition for Asheville-Buncombe County, which concluded that the five-day event injected $14 million into the county’s economy, including $696,000 in local and state taxes. Frost calls that “a pretty good return.”

Merrill also faults Frost’s successful push to give Mountain BizWorks $50,000 in economic development money for the nonprofit’s small-business microloan program. “It’s not fair to hand-pick who you give taxpayer money to and not have them go through the same process as every other nonprofit,” she asserts. But Merrill doesn’t stop there. “There’s a conflict of interest when you personally, as a commissioner, have received funds for your business from that nonprofit,” she alleges.

However, Frost, who owns the Bed & Biscuit pet boarding facility in Black Mountain, responds: “I’ve never received money from Mountain BizWorks. We worked with several different groups to see who would be best for the county to partner with, and Mountain BizWorks was by far the best.”

In April the nonprofit leveraged that county money to receive an additional $300,000 in federal funding. “And they’ve been able to help six businesses and create 31 more jobs,” says Frost. “These are truly small loans, but that sometimes makes a difference in whether a business can get started or expand.”

Looking ahead, Frost says her top priority would be “creating living-wage jobs.” Besides providing economic incentives to encourage companies such as GE Aviation to expand their presence here, Frost says she wants to establish a new program to “incentivize” major employers such as Ingles to raise their pay.

“Right now, taxpayers are paying for employees who don’t make a living wage,” says Frost, adding that these workers must often rely on government subsidies to get by. Another top priority is looking for ways to partner with day care facilities to provide around-the-clock service for people working nontraditional hours. “If we can work on those two things, then we can lift people out of poverty,” she says.

Merrill, on the other hand, says she’d “work to make education needs a top priority.” This year, the commissioners increased funding for the Buncombe County and Asheville City school systems by a combined $3.1 million compared with 2013, mostly to help cover teacher raises. But Merrill, responding to the Children First candidate questionnaire, wrote, “The county could do better to prioritize resources so more money can be allocated to classrooms and teacher pay.”

To facilitate job growth, Merrill wants to re-evaluate what she sees as an “abundance of restrictions” in order to make the county “more conducive for potential employers.” As currently written, she maintains, the zoning, outdoor lighting and signage rules are examples of “blanket ordinances that hurt businesses. They need to be more specific.”

And when it comes to using incentives to encourage companies to expand, Merrill says she has mixed feelings. “My tendency is to lean on the side of the taxpayer,” she says. “But that said, I do understand that each circumstance is different. In the case of GE, I understand there were 300 jobs at stake. Each incentive situation is unique, so I can’t give a blanket answer.”

Meanwhile, due to her marketing background, Merrill would also be interested in serving on the board of the Asheville Convention and Visitors Bureau. “Tourism is a great revenue source for our county,” she says. “It’s an area I’d like to see continue to grow.”

District 3

Political newcomers Miranda DeBruhl and Nancy Waldrop are squaring off in District 3, which stretches from Arden to Sandy Mush and includes the most conservative parts of the county. Waldrop is mounting an unaffiliated campaign after DeBruhl defeated incumbent David King, Waldrop’s husband, in this spring’s Republican primary.

To get on the ballot, Waldrop needed to collect 2,300 signatures from registered voters in the district. With the help of over 100 volunteers, Waldrop gathered nearly 4,000 signatures — more than the 2,054 votes DeBruhl received in the primary.

A retired Buncombe County public school teacher and real estate agent, Waldrop says she jumped into the race “to give voters a choice.” Previously a lifelong registered Republican, she switched to unaffiliated this year after witnessing “this huge resistance in the Republican Party to working with people of differing views,” she says. “The letter beside your name doesn’t determine who you are. Your character determines who you are. I got very tired of the polarization.”

In her campaign announcement, Waldrop characterized DeBruhl as an “ultraconservative,” and she worries that her opponent would value political ideology over practical considerations. DeBruhl dismisses those charges as “political rhetoric,” saying, “This is someone who entered the race after her husband lost in May. … I think it’s very hypocritical.”

DeBruhl, a nurse and convenience store owner, says she decided to run for the Board of Commissioners after becoming “extremely concerned when they passed the [2013] budget.”

“The tax increase and the pay raise is when red flags really started going up for me,” she explains. “Commissioners should never allow themselves to be paid extra when they’re putting more of a burden on the taxpayer. Money could’ve been either saved or generated to avoid the tax increase.” If elected, she says, her focus will be on “smart spending” and prioritizing “core services.”

Asked how, specifically, she would generate revenue or cut spending, DeBruhl says she wants the county to scrutinize hiring and sell “unused assets” such as the Busbee Community Center property. “I would look at any unfilled positions that have been vacant for a while. Maybe we don’t really need to fill that position.”

In a move that DeBruhl says she supports, 125 county employees opted this summer to take an early retirement incentive, which County Manager Wanda Greene says will save the county more than $1 million a year.

On her website, DeBruhl says another priority would be “to ensure tax dollars are spent efficiently on items desired by our citizens, not just special interest groups.” Asked for examples of such spending and groups, DeBruhl says she’s “not going to name names.” Instead, she continues, “I want to be guarded … against the appearance of a lot of pet projects or pandering.”

As a former student, DeBruhl says she’d be particularly interested in issues involving A-B Tech. And as a nurse, she’d also focus on health concerns, though she doesn’t have specific changes in mind at this time. “I think it would be presumptuous of me to have a plan and changes that I would like to be implemented,” she says. “I’d start by talking to staff and listening to their recommendations.”

Waldrop, meanwhile, says she thinks the county is going in the right direction overall and wants to stay the course. She cites a long list of moves made in the last couple of years that she supports, from increasing school funding to offering GE Aviation millions in incentives in exchange for expanding its local operations.

Such incentives are often controversial, Waldrop concedes, but she says the county “can’t afford not to do it. Like it or hate it all you want, you can’t not play by those rules if you want jobs for your county.”

Overall, she continues, “What I see happening in Buncombe County is extremely positive: There is growth here.”

And to keep up the progress, Waldrop says a top goal is “increasing community participation.” She says she’ll explore various ways to do that, including holding more community meetings outside of downtown Asheville. “In some form or fashion, I feel like it needs to happen,” says Waldrop.

For her, such participation has already included volunteers from the Sierra Club of Western North Carolina, who helped collect signatures in the write-in campaign that got her on the ballot. Waldrop says she supports a wide range of county environmental policies, including carbon reduction goals, land conservation easements and the dark sky ordinance to limit light pollution.

DeBruhl, however, has been critical of the county’s goal of eventually reducing carbon emissions by 80 percent, saying, “It was passed without the commissioners even knowing the final cost.” As for the other above-mentioned environmental issues, DeBruhl says she’d need to do more research before forming an opinion.

“I will support any environmental proposal that doesn’t harm our economy or our budget or business environment,” DeBruhl declares. “It’s a juggling act. I’m really looking forward to getting in there and digging in and having the staff there to assist me.”

For Waldrop, though, the county’s initial carbon reduction plans — updating heating systems and lighting in county-owned buildings — makes sound financial as well as environmental sense. “I grew up being told to turn off the lights all the time, so I don’t think this is something particularly new,” she points out, adding, “I think it’s vital that we conserve our energy.”

And just as with other county policies, Waldrop says she wants the carbon reduction plan regularly assessed for cost-effectiveness. “If you continually re-evaluate what you’re doing (as you should do, in whatever business you’re in), and you find out it isn’t working, then you make adjustments to it.”

Stay tuned to mountainx.com/news/politics-elections for updates from the campaign trail.

Good article by Jake Frankel.

Thanks Lan.