With deadlines looming to sign up for or renew coverage under President Obama’s controversial health care law, much confusion remains about what the 2010 law does and how well it’s working. And though more Buncombe County residents now have health insurance than ever before, many of the poorest are still falling through the cracks.

Nationwide, the number of uninsured citizens has plummeted. Between 2008 and 2013, 13 to 14 percent of Americans lacked health insurance, census figures show. Last year, when many of the law’s provisions kicked in, that number dropped to 10.4 percent — a difference of nearly 9 million people.

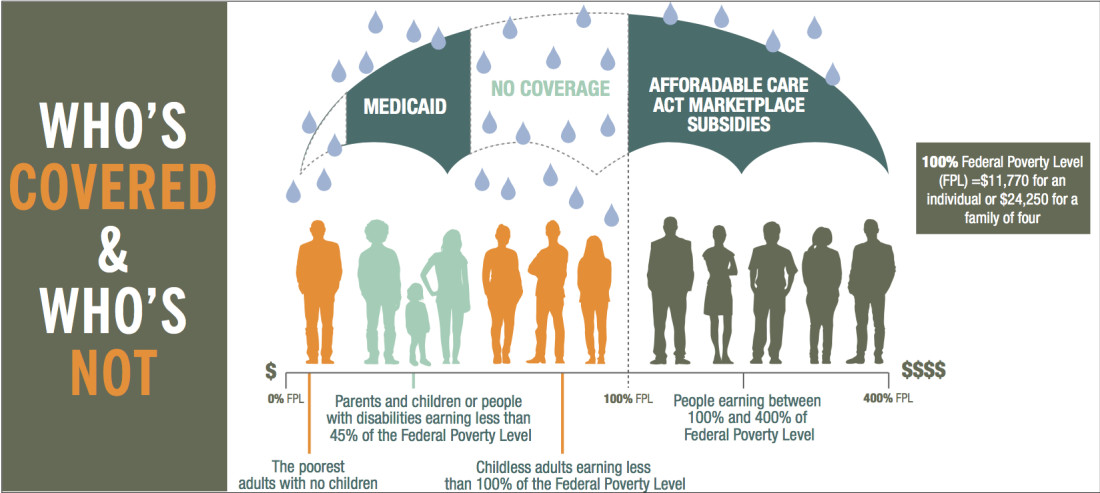

Meanwhile, 19 percent of Buncombe County residents lacked health insurance in the fall of 2013, when people first began logging on to healthcare.gov to explore their options for coverage that would start Jan. 1, 2014. Today, that number stands at 14 percent, and more folks will undoubtedly enroll in the coming weeks. But when it comes to getting people insured, the South as a whole is still lagging behind. And one big reason is that most Southern states, including North Carolina, have chosen not to accept a key component of the law: a federally funded expansion of Medicaid designed to cover those too poor to qualify for tax credits under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

Help is available

Roughly one-third of those Americans who do have health insurance get it via government programs (such as Medicare, Medicaid, state health plans and military health benefits); the rest are insured by private companies, typically through their work. The big change in 2014 was due to individuals directly purchasing private insurance through the state and federal marketplaces set up under the health care law, as well as new Medicaid enrollment.

But figuring out the best way to get affordable coverage (which the law defines as costing less than 9.5 percent of yearly household income) isn’t always easy.

“We understand that it can be confusing and intimidating,” says Evie White, communications manager for Pisgah Legal Services. “But one of the best resources for people feeling lost are the advisers known as ‘navigators.’ Many people will research or attempt to sign up for insurance on their own but need assistance to complete the process. Our navigators are trained to provide that help, and it’s absolutely free. Without it, hundreds of people would fall through the cracks and would not be given the fair and unbiased information they need to enroll in health insurance.”

Staff and volunteers at local nonprofits such as Pisgah Legal, the Council on Aging, the Western Carolina Medical Society and WNC Community Health Services (which operates the Minnie Jones Health Center) have put in thousands of hours helping folks sign up for coverage through the federal marketplace (see box, “Finding Help”). Thanks in part to these efforts, Buncombe County’s uninsured rate declined by 1 percent this past year. That means about 2,400 local people (and over 10,000 since 2013) have insurance who didn’t before. Although Buncombe is the state’s seventh-most populous county, it ranks fourth in terms of Affordable Care Act enrollment.

But it’s not just for new enrollees. These groups also help folks who’ve lost their health insurance and need to find an alternative, as well as current enrollees who need help renewing their coverage. After Black Mountain resident Melissa Dix lost her job and, consequently, her health insurance, she was worried about getting penalized for not having insurance when she paid her income taxes. This year, the fine will increase to a minimum of $695 per adult (plus half that for each child) up to a maximum of 2.5 percent of household income. Dix’s new job is seasonal and doesn’t offer an insurance plan, so she sat down recently with one of Pisgah Legal’s more than 50 navigators (40 of whom are volunteers). “It went well, actually,” says Dix. “I was surprised at how easy it was.” After about two hours, she was enrolled in a plan through United Healthcare for which, after the tax credits she’ll receive based on her income, Dix will pay just $7.41 per month.

Out in the cold

Misinformation is one of the biggest hurdles to lowering the local uninsured rate.

“In one recent appointment, a man came in saying, ‘I’m only here because the penalty is going up, and I don’t want to pay it,’” navigator Noele Aabye recalls. “But when we helped him examine his options, we discovered that he and his spouse qualified for more than $900 in tax credits. He was relieved to finally get health care coverage after years of being without it, and he was frustrated that he paid the penalty last year and got nothing in return.” Tax credits are available for household incomes of up to 400 percent of the federal poverty line ($47,080 for individuals, $97,000 for a family of four). This year’s open enrollment period runs through Jan. 31, 2016; the deadline for coverage that starts Jan. 1 is Dec. 15.

In Buncombe County, growing numbers of folks now have private insurance, while government insurance is holding fairly steady. “Right now, we’ve got 46,484 people here in Buncombe County on [various government insurance programs],” says Tim Rhodes, a planner/evaluator at the Department of Health and Human Services. That number, however, does not include Medicare (52,876 people as of 2012), because people sign up for that directly, without HHS involvement.

“Our primary focus is ensuring that we do everything we can to get citizens who are eligible for Medicaid, Health Choice or any of the subsidized health care programs enrolled. And if they’re not eligible, or if they get terminated from one of those programs, we’ve also put a lot of work into ensuring that they get connected to another source, be that the Affordable Care Act or a local, federally qualified health center like WNC Community Health Services. The one real gap that we’re still seeing is those folks that are able-bodied, have no children, and are under 100 percent of poverty ($11,770 for a singe adult) that just can’t qualify for Medicaid or the Affordable Care Act. Those folks are still sort of out in the cold.”

Medicaid matters

Buncombe County is somewhat comparable to Fayette County, Ky., which includes the city of Lexington. Buncombe covers a much larger area; Fayette has a somewhat larger and more diverse population. But the high school graduation rate, the median household income and the poverty rate are similar, and Obama won both counties in 2008 and 2012 while his opponents carried all the surrounding counties.

There is one big difference, though: Since 2013, Fayette County has seen its uninsured rate drop almost twice as much as Buncombe’s. And that’s where Medicaid enters the picture.

A provision in the health care law calls for expanding Medicaid to include anyone earning less than 138 percent of the federal poverty level ($16,243 for individuals, $33,465 for a family of four). Federal funding would initially cover the entire cost of the expansion and most of it after that. But the individual states administer Medicaid, and in 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that each state government could choose whether to accept the health law’s offer to expand its program. To date, only two Southern states — Kentucky and Arkansas — have agreed to do so. The rest of the Old South, as well as several other states, have rejected the offer, arguing that it would be too expensive once states have to start assuming a small percentage of the cost. These are the same states where health insurance coverage is lagging; all of them have either a Republican-controlled legislature, a Republican governor or both.

“North Carolina is one of 19 states that hasn’t expanded its Medicaid program under the Affordable Care Act to close the coverage gap and cover our lowest-income adults and families,” says Jaclyn Kiger, an attorney at Pisgah Legal Services. “Medicaid only covers about 30 percent of the poor in North Carolina as the law stands today. This is because of the strict eligibility criteria: You have to be poor and fit into one of the eligibility categories. This means that, in our state, half a million poor people are left out of the Medicaid system because they don’t fall into the right category to qualify and they’re too poor to qualify for financial assistance through the ACA.”

Last year, Pisgah Legal navigators helped more than 1,000 people sort out their health insurance options. At least 14 percent of those folks had incomes below the federal poverty line but didn’t qualify for Medicaid. The nonprofit law firm expects similar numbers this year, except that anywhere from one-third to half of those being helped will probably be re-enrolling.

Other Western North Carolina counties, most of which have a higher percentage of residents below the poverty line than Buncombe, are also struggling to reduce the number of uninsured.

Last fall, The New York Times partnered with Enroll America and Civis Analytics to project, county by county, uninsured rates if the Supreme Court hadn’t made Medicaid expansion optional. The analysis predicted a 10.9 percent rate for Buncombe and 10.1 percent for Swain, which currently has the highest uninsured rate in WNC.

Resistance in Raleigh

In early August, as the N.C. Senate debated a bill to reform the state’s Medicaid program, Sen. Terry Van Duyn of Buncombe County proposed an amendment that would have made North Carolinians with incomes under 133 percent of the federal poverty level eligible for Medicaid. The broader expansion offered by the federal law, notes Rhodes, would benefit anywhere from 8,500 to over 10,000 Buncombe County residents.

Some Republicans, including Gov. Pat McCrory, have shown an interest in expanding Medicaid but said that controlling costs in the existing system should come first. The bill in question, which was signed into law in September, aims to do exactly that.

Republican Sen. Tom Apodaca defended his vote against Van Duyn’s amendment. “I’ve said all along on the expansion of Medicaid that I can’t support it until we fix our current Medicaid system. We did take strong measures toward that goal in the General Assembly this year, and we’d like to get those up and running and see if that gives us some stability in the cost of Medicaid, and then we’d be more than happy to look at expansion and tying it together.” The retiring seven-term state senator represents Henderson and Transylvania counties and a small portion of Buncombe.

North Carolina’s Medicaid reform relies on provider networks (including private managed care organizations) to coordinate care; the law anticipates significant savings, because the state caps how much it spends on the program, putting third parties on the hook for any additional costs. Proponents of the change say the existing system rewards more, but not necessarily better, care. The reform aims to reward outcomes.

But Van Duyn, who’s served as a volunteer navigator and formerly chaired Pisgah Legal Services’ board, fears the Medicaid reform “will exacerbate the problem.”

“If providers have to compete on price to be included in a managed care organization’s network, will they be able to take uninsured patients?” she asks. “For that matter, will they be able to afford being part of an MCO network at all? In North Carolina, 90 percent of our health care providers take Medicaid. In Florida, under managed care, that number is 54 percent.”

Mission Health has joined a group of 10 other health-care providers in the state in order to explore becoming a Medicaid managed care company. The 11 hospital systems announced collaboration as a provider-led and patient-centered care corporation that will compete to become one of three to contract with North Carolina to provide services for Medicaid beneficiaries throughout the state.

Other options

If you’re too young for Medicare and don’t qualify for either the Affordable Care Act or Medicaid, your prospects for finding affordable health insurance may seem bleak. But there are still ways to avoid falling through the cracks, says Jim Barrett, Pisgah Legal’s longtime executive director.

“They might consider doing what it takes to become eligible [for tax credits] based on income. Sometimes they’re just a little bit below the cutoff. We’ve seen people who just needed to keep track of their baby-sitting money or other part-time work to become eligible.” In Barrett’s view, adding a little to your tax bill is a small price to pay for making sure you have insurance coverage. “Your health is important, and you might need ongoing treatment,” he points out.

And if that doesn’t work, there are other options.

“We can refer people to the clinics, such as Minnie Jones or the new MAHEC clinic coming online for homeless people,” notes Barrett. Asheville Buncombe Community Christian Ministry’s clinic offers primary care and medication assistance. And Project Access, a program of the Western Carolina Medical Society, helps some indigent patients obtain more extensive or specialized care.

Mission Hospital also treats many uninsured people each year, and Larry E. Hill, vice president of finance, says his organization’s “experience with the Affordable Care Act seems to be in line with what many of our nation’s hospitals are seeing.” Comparing the first fiscal year under the law with the previous year, he reports, “Mission Hospital saw approximately 20 percent less uninsured patients. In addition, the cost to provide charity care declined by about 32 percent.”

Nonetheless, he continues, “Mission Hospital’s community benefit for FY15 was $132 million, up $2 million from FY14.” Much of that money was in the form of grants to local organizations.

Minimal impact

Over at WNC Community Health Services, however, the health care law’s “impact on our organization has been minimal,” says Scott Parker, director of development and collaboration. “The average patient here is at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty level. … Among that group, we can have folks who are uninsured, underinsured or have Medicare or Medicaid. Right now, about 60 percent of our patients are uninsured, which is a high percentage for a community health center [in this state]. In Buncombe County, we’re pretty well considered the primary safety net agency.

“What has impacted us the most,” continues Parker, “is the failure to expand Medicaid in North Carolina, because several thousand of our patients who are currently uninsured … would have a source of payment, which would help us see more uninsured people here.”

Can’t find out who, but someone from the North Carolina legislature went to Scottsdale AZ this past weekend, for an ALEC (American Legislative Exchange Council) conference. They went specifically to brag about the new Medicaid “reform” bill: “ALEC Workshop: North Carolina Medicaid Reform: Here’s What We Did”

http://www.alec.org/snps-agenda/

ALEC tweeted immediately after the anonymous presentation: “North Carolina successfully reformed #Medicaid despite #ObamaCare. Great example of what real #healthcare reform looks like.”

Somebody touted NC’s Medicaid law at ALEC, and ALEC appears to love it. So why is no one taking credit for having given the presentation? Repeated queries to Rep. Chuck McGrady have gone unanswered. BTW, who’s that standing next to the Governor as he signs the bill (which the News & Observer calls by it’s proper name)?:

McCrory signs Medicaid privatization bill

http://www.newsobserver.com/news/politics-government/politics-columns-blogs/under-the-dome/article36309216.html

Why was Chuck McGrady not interviewed for this article, given that he was clearly a central player in the privatization of North Carolina’s Medicaid program?

Clearly Mr. McGrady, is an important player in the Medicaid reform part of this story, but the focus here is on the failure to expand Medicaid and the action item on that was in the senate. There is still room to explore the nature of this state’s chosen version of reform. I hope to have the chance to look at how it is being implemented over the coming years. I will have a question or two for the representative of the 117th district.

Thanks Able – great article.

I’m in that hole. and I’m glad the state didn’t cooperate with the feds because medicaid pays for fertility treatments, maternity care, infant care and lots of stuff that is enabling environmental damage from overpopulation, I would far rather do without than destroy the planet. Mcrory’s outrage was covering parents.