by John Boyle, avlwatchdog.org

On a busy day, some 300 people visit the AHOPE day shelter on the western outskirts of downtown Asheville for a free meal, a chance to shower or to collect their mail. They all share the same plight: homelessness.

It’s not unusual for arguments to break out and for conversations to turn delusional and paranoid, because almost all of the people at the gray, two-story AHOPE shelter share something else, local experts say: They have some form of mental illness.

“Ninety-plus percent of our folks have S.P.M.I. [severe persistent mental illness],” said Luc Gay, a manager with Homeward Bound, the nonprofit organization that runs AHOPE.

“And maybe 50% have access to care,” Gay said. “But how often they access it is a whole other question.”

Untreated mental illness is the nexus of many of the problems contributing to a perception that downtown Asheville has become less safe. As Asheville Watchdog previously reported in our series “Down Town,” mental illness often goes hand in hand with drug use — mainly methamphetamine and fentanyl — and meth often causes bizarre and aggressive behavior.

But someone with ongoing mental health needs in Western North Carolina sometimes has to wait weeks or even months for an appointment for treatment, The Watchdog learned.

And because many of the people living on the streets don’t have health insurance, or money for treatment, any treatment they get is often inadequate.

Sometimes, when psychotic episodes play out in public, the only option is jail.

That’s because Asheville’s homeless shelters have entrance restrictions including sobriety — no active drug or alcohol use — and Buncombe County doesn’t have a 24-hour mental health crisis center, a successful response that some cities have adopted.

“The reality is the detention facility is the low-barrier shelter for Buncombe County,” Sheriff’s Office spokesperson Aaron Sarver said on a recent tour of the jail’s medical wing.

According to the North Carolina Department of Health & Human Services, each day hundreds of people in the state wait inside hospital emergency departments for behavioral health care. As Asheville Watchdog reported in Part 4 of this series, that often means nurses in the understaffed emergency department at Mission Hospital struggle to provide care to mentally unstable patients, some of whom get violent.

“I think anyone would tell you we’re kind of in a crisis right now, without enough treatment options,” said Pam Jaillet, executive director of National Alliance on Mental Illness, Western North Carolina. “And it’s a very difficult process to navigate the system. There’s so many hurdles to go past.”

State shift limits options

Two decades ago, North Carolina, like many other states, moved to privatize the treatment of mental health, in the widely shared belief that patients would be better treated in the community, in less restrictive settings than state-run psychiatric hospitals.

But in refusing to expand Medicaid for years, the legislature also failed to provide incentives for the privatization of mental health care, health care experts said. At the same time, state lawmakers did not approve enough money to fund alternative community care options, or to replace the number of beds lost when state hospitals were shuttered.

What was supposed to become a more efficient system that provided care to people in their communities instead of institutions quickly devolved into the opposite: a system where demand for mental health and drug treatment, especially for crisis care, outstripped supply.

One in five adults in North Carolina have a mental illness — some 1.5 million people — and more than half of those are not receiving treatment, according to the report, “2022: The State of Mental Health in America,” by the nonprofit Mental Health America. Nationally, 49.6 million people have a mental illness, the group says.

Nowhere else to go but jail

With treatment options lacking or involving long waits — Jaillet said sometimes it takes three to four months for a person needing mental health care to get an appointment — those in need often end up in the county jail.

“I think since the state system went away from mental health years ago, we started seeing those people here because they had nowhere else to go,” Executive Lt. Alex Allman, a supervisor in the Buncombe County Detention Center, said during a recent tour of the medical wing. “And then they were having interactions on the outside with law enforcement, and that’s how we ended up here.”

The jail typically houses about 400 inmates. Allman estimated that 75% or more of those have a mental health disorder, a drug problem, or a combination of the two, but the official numbers are lower.

Sarah Gayton, Buncombe County Detention Center’s Medical Assisted Treatment program coordinator, said the jail relies on inmates to self-report, and some are reluctant to disclose drug use for fear of more charges, or they have other maladies that they disclose instead.

Still, the official intake data show a significant portion of the jail population has drug and mental health issues. From October 2022 through January 2023, the jail conducted 1,343 interviews with incoming inmates and found:

- 43% reported a history of drug use.

- 56% reported a mental health diagnosis.

- 43% arrived with an acute mental health issue, according to a registered nurse’s assessment.

- 22% reported they would be homeless upon release.

With the number of unhoused people in Asheville — 637 according to the year-old 2022 Point-in-Time census — that translates into more people living on the streets with mental illnesses, addictions or often both.

Nationwide, in 2021 an estimated 14.1 million people aged 18 or older, 5.5% of the adult population, had a serious mental illness, according to the National Institute of Mental Health.

Locally, even those with access to mental health care struggle to get treatment, said Gay of AHOPE and two of his coworkers, outreach case managers Hillary Jones and River Hachet. That’s because people with such serious mental illnesses as schizophrenia often have severe paranoia, and they have trouble maintaining a train of thought long enough to concentrate on catching buses on time, or remembering where treatment offices are, they said.

Jones said the No. 1 barrier to treatment for folks with serious mental illness is insurance. If they have not qualified for federal disability insurance or the state Medicaid program, they’re unlikely to receive meaningful treatment, he said.

“Then the only thing they can really be offered is group therapy,” Jones said. “And for people with serious, persistent mental illness [SPMI], that’s not the adequate treatment.”

‘I’m off my meds right now’

SPMI refers to severe mental disorders that tend to be disabling. They include major depression, bipolar disorders, schizophrenia and borderline personality disorder. Typically, they require pharmaceutical treatment with antipsychotic drugs, but that’s also unlikely without health insurance. Even those who have health insurance sometimes stop taking their medications.

“I need to get my stuff,” said Chris, a tall, lanky 41-year-old man with schizophrenia who had stopped by AHOPE on a recent Monday morning. Asheville Watchdog is using only his first name to protect his privacy.

“I’m off of my meds,” Chris said. “I’m off on my meds right now.”

Having lost his wallet and identification, Chris needed to get to the DMV office on Patton Avenue. With no ID, access to his meds would be problematic. AHOPE staff had a bus pass waiting for him, but Chris seemed confused and wanted to call his sister, his attorney or a friend for a ride.

For many in Asheville going through a psychotic episode, the first stop is Mission Hospital and its 82-bed Copestone Behavioral Health Unit.

Chris said he’s been to Copestone before, and he’s had “both good and bad experiences there.”

“Whenever you take the medications, it seems like it’s all right,” Chris said. “You just sit there and sleep all day. Whenever you don’t want to take the meds, it’s bad.”

Originally from Atlanta, Chris said he’s been in Asheville for about 10 years and receives federal food stamps, disability income and health insurance. His mother died a few years ago, he said, but he still has his sister in the area.

Chris has a tattoo on his chest that honors his mother — the letter “M” in a star.

Previously, he said, he had an apartment, but recently he has been without a place to live. Still bundled up in two coats at 10 a.m., Chris said he spent the weekend sleeping outside.

Asked if it’s hard to stay on his medications, Chris said, “People really don’t do that. Only when they’re at the hospital.”

Navigating a labyrinthine system

Chris Fink, a retired management consultant, chairs the Community Inclusion Committee of the local National Alliance on Mental Illness, Western North Carolina chapter and sits on NAMI’s state board. With a loved one diagnosed with schizophrenia-affective disorder, he’s also navigated the mental health system for 10 years.

Schizophrenia-affective disorder is “marked by a combination of schizophrenia symptoms, such as hallucinations or delusions, and mood disorder symptoms, such as depression or mania,” according to the Mayo Clinic. Fink said his loved one has depressive symptoms.

Fink, who’s lived in Asheville for a decade, said he believes the people downtown behaving erratically are likely dealing with more serious mental illnesses — and with trying to find consistent treatment.

“It becomes a real journey of trying to find care, and finding care that is insurance-covered, or affordable, or the individual over time has become eligible for community health care” typically covered by Medicaid, Fink said. “You could talk to any number of families in and around Asheville who have spent fortunes getting care for their children.”

Fink said he breaks the local treatment system into “columns,” noting that hospitals are in the first column, providing care to people in danger of harming themselves or others, or who are unable to function on their own. Hospitals essentially provide crisis treatment and move patients out in a matter of days, he said.

The next column includes community health providers that typically are eligible for Medicaid reimbursements. As Mental Health America notes, “Medicaid is the largest payer for mental health services in the U.S.”

After the privatization shift two decades ago, North Carolina split the state into seven zones, which was subsequently reduced to six.

“And each zone is run by what’s commonly referred to as an MCO, or managed care organization,” Fink said, noting that the state calls them Local Management Entities. “They are responsible for the dissemination of behavioral health services in the public system, within their operating geography.”

In Western North Carolina, the MCO is Vaya Health. On its website, Vaya Health states it “oversees publicly funded behavioral health and intellectual/developmental disability services across a 31-county region of North Carolina,” managing Medicaid, federal, state and local funding.

Fink, who serves on Vaya Health’s Human Rights Committee, puts it this way: “Anybody around town who is not a private practitioner, they’re in the Vaya system one way or another.”

Fink identified the third column as “everyday people with health insurance, and they’re seeking treatment.” They were helped during COVID because health insurers started to provide more acceptance and a greater level of benefits to people seeking mental health support, but that also put more pressure on providers, he said.

Lastly, the fourth column is what Fink called “concierge care,” or people who are in the private payment system and have health insurance, “but they have the means to pay for personalized mental health services.” This typically involves care at high-end treatment centers.

Physical and mental health connected

Buncombe County, as Fink described it, is “replete with mental health professionals.”

The state Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), which licenses mental health and substance abuse providers, has a breakdown of providers by county, excluding private practice doctors and hospitals. Some facilities provide both services, but in Buncombe County, substance abuse centers vastly outnumber mental health treatment facilities. The state’s website lists seven mental health facilities in Buncombe with a total of 30 beds, compared to 32 substance abuse treatment facilities with 244 beds.

“Substance abuse, alcohol treatment rehab — those services for the past 10 to 15 years have been widely covered by personal health insurance,” Fink said. “That’s why those facilities have cropped up all over the place.”

Experts say illicit drug use often accompanies mental illness as people seek to self-medicate, or to escape their circumstances.

At Vaya Health, spokesperson Allison Inman said, the pandemic “really pulled back the curtain on the connection between mental and physical health, as well as the lack of accessible screenings and services for people seeking mental health care.”

“And although there’s been a noticeable reduction in the stigma, normalizing mental health doesn’t equate to available, accessible treatment,” Inman said. “So, what can — and does — happen is that some individuals seek relief from their mental health conditions through substance use, which can lead to physical health issues and/or substance use disorders.”

Inman said studies have shown an increase in substance use and drug overdose deaths since the pandemic began.

“The surge in demand for behavioral health services has put an immense burden on health care workers in those fields, so there’s been significant burnout and attrition throughout the behavioral health care world,” Inman said.

‘95 percent of the people we see have nobody’

From his own experience, Fink well knows that those with mental illness have vast fluctuations in mood and symptoms. Medication helps but ebbs and flows in effectiveness, he said.

This is often exhausting for families, as it “creates a lot of disruption,” Fink said. And when the money runs out, so, too, do care options because of inadequate insurance.

Complicating matters, Fink said, if a parent helps their grown child pay for rent to fend off eviction, or for a cell phone to keep in touch, that could disqualify them from publicly funded coverage in some cases. He said he feels fortunate that his loved one is living on his own in an Asheville group home.

“What I hear all the time from people is, ‘Oh my gosh, your [loved one] is so lucky, because you’re supporting him,” Fink said. “‘What you don’t understand is that 95% of the people we see have nobody.’”

Families either run out of money and patience, “or they’ve just given up hope,” Fink said.

“Whatever combination, the individual is out here on their own, trying to figure out how to navigate their life and get the services they need in a system which is very complicated to understand,” he said.

At AHOPE, Jones said the “mental health resources we do have are spread very thin,” and providers have very large caseloads. She sees a need for mobile treatment teams on the streets.

Hachet, Jones’s coworker, offered a simple solution, albeit one that may sound like wishful thinking.

“We need 630 housing units,” she said, referring to Asheville’s homeless population and the theory that health care, including mental health care, starts with having a place to live.

One family’s journey

Barnardsville resident Carolyn R., a retired nurse who asked that her last name not be used for privacy reasons, said she feels fortunate that her loved one is being cared for and has a permanent place to live, an assisted living facility in Candler. It has few activities for people like her relative, though, a man in his mid-20s with schizophrenia-affective disorder.

“It’s been a lifetime for him of struggles — and for us just trying to find answers,” Carolyn said. “Just trying to find a cure, really, is what we wanted.”

The disorder is treatable, but it has no cure.

A mountain native, Carolyn and her husband spent 25 years in Florida before returning to Buncombe County eight years ago. She’s 65, a retired nurse who’s active in NAMI, and runs a support group for families.

Their loved one was just 4 years old the first time he told his parents he was hearing a voice telling him to say something he didn’t want to say. Doctors examined the child at 7 but said he had attention deficit disorder.

“In high school, he started dabbling in drugs, and that just exacerbated the problem,” Carolyn said.

As a senior in high school, the young man went to California for mental health treatment. When he returned, he had a number of psychotic episodes, including some that were drug-induced, Carolyn said.

Four months, at $20,000 a month

The family paid for him to stay at a private treatment center in Polk County for four months.

“We used part of our retirement savings for him to stay there,” Carolyn said. “At the time it was about $20,000 a month, so it’s not for people who don’t have any kind of resources.”

They couldn’t afford that long term, she said, and tried about four years ago to get their loved one into the Julian F. Keith Alcohol and Drug Abuse Treatment Center, a state-run facility in Black Mountain. They were unsuccessful and settled on another treatment facility in Waynesville.

While there, their loved one experienced a psychotic episode. The Waynesville center sent him to the Haywood Regional Hospital emergency department. Between 2 a.m. and 3 a.m. that night, the hospital said he was stable, but Carolyn said they were sleep-deprived and asked that he stay the night.

“He started walking to Asheville from Waynesville,” she said. “He got picked up by a police officer who dropped him at the county line.”

A Buncombe County Sheriff’s Office deputy brought him to their apartment.

The couple were able to find him a spot in the RHA Behavioral Health Urgent Care in Asheville, and then in a hospital. He now has an “Assertive Community Team,” which includes a psychiatrist and a counselor.

Their journey has been difficult and included several episodes of violence.

“A couple of years ago, we had him in an apartment — he was doing independent living through VAYA,” Carolyn said. “But he wasn’t taking his meds like he was supposed to.”

While in a car with the couple one day on I-26, she said, their loved one started punching her husband and then her, breaking her nose. They went to the emergency room, and their loved one went to jail.

Still, Carolyn considers her family fortunate. Their loved one is disabled and unable to hold a job but has Medicare and Medicaid insurance, and she said she’s appreciative that he’s not strung out on drugs and living on the streets.

“But these places, they’re not ideal,” she said. “There’s nothing for him to do. For a young person, they just sit around. They smoke. A lot of times, he just lays in bed. It’s kind of a sad existence. On other hand, he’s receiving the highest level of care for his diagnosis and his disability in our area.”

Medicaid expansion coming

In the “2022 State of Mental Health in America,” only seven states had more uninsured adults with mental illness than North Carolina. And more than 300,000 adults in the state admitted they had serious thoughts of suicide.

Nationally, the report concluded that “although adults who did not have insurance coverage were significantly less likely to receive treatment than those who did, 54% of people covered by health insurance still did not receive mental health treatment. Almost a quarter [24.7%] of all adults with a mental illness reported that they were not able to receive the treatment they needed. This number has not declined since 2011.”

For adults with a substance use disorder in the past year, North Carolina ranks number 13, at 7.26%, or 576,000 people.

The MHA report noted that studies have shown, “Medicaid expansion is associated with a significant reduction in the percentage of adults with depression who are uninsured, and in delaying mental health care because of cost. Medicaid expansion is also an issue of mental health equity, as expansion has been found to reduce racial disparities in health coverage.”

North Carolina’s General Assembly voted this year to expand Medicaid and Gov. Roy Cooper signed the bill. It should provide health coverage to more than 600,000 North Carolinians, the governor’s office said in a press release.

“Without Medicaid expansion, North Carolina has missed out on an estimated $521 million each month that could go to improving mental health and helping rural hospitals remain open,” the press release stated.

But Fink pointed out that Medicaid expansion might not be the panacea everyone expects, partly because providers might not be ready for the surge and because of how the system works.

“What people don’t really spend a lot of time talking about is exactly how do you get eligible?” Fink said. “What combination of health care symptoms at large, and income, enable you to get Medicaid services? And if you don’t fall into that group, where do you get your services?”

Gov. Cooper, a Democrat, also has proposed a budget for the upcoming fiscal year that includes $1 billion in behavioral health and substance abuse funding. But the Republican-controlled General Assembly has to pass the state’s budget before Cooper signs it.

Even if it does go through, Fink stressed that much “remedial repair” needs to be done.

Treatment is scarce, demand high

At Sunrise Community for Recovery and Wellness in Asheville, the nonprofit fills “gaps in systems of care” for vulnerable populations. Staff use “their lived experience with mental health and substance use disorders, houselessness or incarceration to help others with their life journey,” according to its website.

Executive Director Sue Polston said they do not offer direct treatment, but rather they help people find their own path to recovery through peer support, resources, and help with employment.

“There’s always been a lack of treatment beds or some type of treatment service,” Polston said. “The need has always outweighed what is available, but since COVID, especially, we’ve seen such an influx of mental health challenges, now it’s off the charts. The number of beds really haven’t increased, or the number of programs — there’s still a huge gap.”

While she said she thinks services have increased in some sectors, Polston said “there’s still a lot of work to be done. And over the last two years, that need has skyrocketed.”

Sunrise opened in 2016, and demand was already strong.

“We had 30,000 peer support interactions in 2016, ’17 and ’18,” Polston said. “Last year, we had 34,000, just in the one year. We doubled our numbers one year to the next.”

Options for the severely ill

Those suffering from a mental health or drug crisis often are referred to Mission Hospital, to the privately run RHA Health Services, or to the state-run Julian F. Keith Alcohol and Drug Abuse Treatment Center.

Often just called “ADATC,” the 54-bed Black Mountain facility is one of two state-operated centers that provides medically monitored detoxification/crisis stabilization, and short-term treatment.

The ADATCs accept Medicaid, Medicare and sliding scale fees, as well as private insurance. Both facility webpages state: “Admission is available to any adult in our region regardless of financial resources or insurance status. Patients pay on a sliding scale according to their income.”

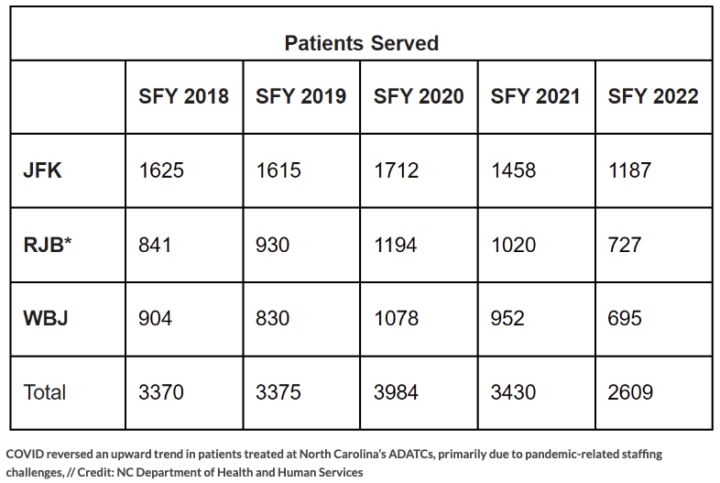

In Black Mountain, the ADATC over the past five fiscal years has consistently treated the highest number of patients of the state’s centers, including 1,187 in the 2022 fiscal year, which ended June 30. The state previously ran three centers, but one closed this year.

The Walter B. Jones Center ADATC (WBJ) is in Greenville, in eastern North Carolina; while the R.J. Blackley center (RJB) was in Butner, serving the middle part of the state. The state announced in December 2022 that the R.J. Blackley center would be repurposed into a 54-bed inpatient psychiatric hospital for children and adolescents, operated by UNC Health.

The Blackley ADATC permanently closed March 1. The counties previously served by the Blackley center were reallocated to the two remaining ADATCs.

North Carolina also operates three psychiatric hospitals that provide longer-term care. Broughton Hospital, located in Morganton in Burke County about 55 miles from Asheville, serves people with mental illness in the westernmost 37 counties of North Carolina, about 35 percent of the state’s total population. Broughton serves youths, adults and geriatric patients, but those in the mental health field in Buncombe County said it’s tough to get patients placed there because of limited space.

Broughton’s website says it serves about 770 patients per year with an average daily cost of $971. It employs approximately 1,200 people and has a $120 million annual operating budget.

Mission’s Copestone Behavioral Health Unit, located on its St. Joseph’s campus, has 82 inpatient beds serving children, adolescents, adult and geriatric patients, Mission spokesperson Nancy Lindell said.

“Most BHU inpatients are admitted from the Mission ER, and we admit patients based on diagnosis regardless of their insurance or ability to pay,” Lindell said.

Mission’s BHU treats patients with a primary diagnosis of mental illness, although patients sometimes have a secondary diagnosis of substance abuse disorders, Lindell said. Mission’s BHU is not licensed as a primary substance use treatment facility.

“Patients with substance use issues do come to the Mission ER and are treated and stabilized as needed,” Lindell said.

Asheville Watchdog requested statistics for the BHU and the ER on mental health caseloads and demand, but Lindell did not provide the data by deadline.

Last resort: Involuntary commitments

Sam Snead, chief public defender for Buncombe County, said Mission Hospital is “somewhat in crisis mode” when it comes to mental health care. The Public Defender’s office handles involuntary commitments in Buncombe for adults, adolescents and children, “so we know who’s been involuntarily committed each week.”

“And the Mission Hospital triage is, I think, about 800 cases a month,” Snead said. “Now, all those cases aren’t all involuntarily committed [at Mission], but they’re referring folks out to other hospitals. We’re getting, on average, probably 50 a week total for involuntary commitment.”

Mission, which is owned by for-profit, Nashville-based HCA Healthcare, agreed to build a new behavioral health hospital as part of its 2019 purchase of the nonprofit Mission Health System. The new 120-bed Sweeten Creek Mental Health and Wellness Center, scheduled to open later this year, “will allow us to expand our ability to provide inpatient care by 37,” Lindell said.

The Copestone Behavioral Health Unit at Mission will close once the new hospital opens. Staff will move over to the new facility, Lindell said.

Fink said the shortage of treatment facilities is not surprising, especially at hospitals, given the compensation model. Medicaid is the dominant payer for mental health care, and as Fink says, “it pays for everything, but way, way, way less than what you can get from private insurance or the public market.”

Hospitals receive higher reimbursements for heart patients and cancer care, he said.

“If someone comes in with behavioral health, the billing is lousy, the duration is limited, and it takes a lot of staff to deliver this care,” Fink said. “[Hospitals will say], ‘This is a crummy piece of business for us.’”

No other options

Meredith Switzer, executive director of All Souls Counseling Service in Asheville, formerly served as executive director of Homeward Bound. All Souls provides counseling for the uninsured and under-insured.

Clients “come to us because they don’t have other options in the community,” Switzer said. “A lot of times, if there are mental health services available in the community, they’re cost-prohibitive. We also found we have a much shorter wait list than a lot of other providers in the community.”

Their average wait time is about two to three weeks, she said. With private insurance, Switzer said, patients can often wait a month to get services, “and the truth is, when you are trying to access services, you’re trying to access them because you need them right away.”

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the existing dearth of treatment services, while it also created a spike in stress. On top of that, Asheville’s housing market is typically the most expensive in the state for renters, adding to anxiety levels, Switzer noted.

Meanwhile, drugs remain plentiful on the streets, and the nation’s suicide rate is up.

“I think when you look at all of these things, it’s just a perfect storm,” Switzer said. “I think that what we’re seeing in the homeless community is, to be truthful, kind of a reflection of how we’re all feeling so stressed, and so pushed to the margins in so many ways and really overwhelmed with a lot of things that are going on in our community.”

Meanwhile, the state’s move toward privatization two decades ago “dramatically reduced services” for those with substance abuse and mental health issues, Switzer said.

“That’s why this organization started in 2000,” Switzer said. “Two psychologists got together and said, ‘What are we going to do? How are we going to fill this gap, now that these major hospitals, these mental health providers, are shuttering?’ And so we started as a nonprofit, to respond to the need for those who desperately needed mental health services and had really no options in the community.”

Mental health and substance abuse problems ultimately affect everyone, Switzer said. She said since the pandemic, their counseling providers have seen more unpredictable behaviors from clients, including more delusions and extreme behavior.

In short, it’s about vulnerability, said Dr. Shuchin Shukla, a family medicine faculty member and opioid educator at MAHEC Family Health Center in Asheville.

“And the vulnerability in Asheville is the most pronounced in the state,” Shukla said. “It’s the highest cost of living, and I think this is pointing to why we have such a problem with substance use, mixed with homelessness, in our community.”

Like Switzer, Shukla said the stress, anxiety and social isolation of the pandemic worsened the mental health crisis. On top of the shortage of mental health and addiction providers and a housing crunch, some support groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous stopped meeting during COVID.

“I think what we’re seeing downtown.” Shukla said, “is a combination of substance use” and “untreated mental health conditions, all exacerbated by a super-vulnerable population that just can’t get food, shelter, transportation, and their medical and behavioral health needs met,” Shukla said.

Watchdog investigative reporter Sally Kestin contributed to this article.

Asheville Watchdog is a nonprofit news team producing stories that matter to Asheville and surrounding communities. John Boyle has been covering western North Carolina since the 20th century. You can reach him at (828) 337-0941, or via email at jboyle@avlwatchdog.org .

City of Asheville and Buncombe County Government omit Citizens with Disabilities from their versions of equity strategy on a daily basis. Just look for mentions of the disabled, disabilities, or the term Citizens with Disabilities… or the more common persons with disabilities.

The Mayor’s Committee on Citizens with Disabilities hasn’t met since the Bellamy Administration. It was Mayor Bellamy who founded the MCCD.

https://www.ashevillenc.gov/government/mayors-committees/

This is a more expansive perspective on CWD issues versus the ADA, Rehabilitation Act, or IDEA Act: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-persons-disabilities

“Untreated mental illness is the nexus of many of the problems contributing to a perception that downtown Asheville has become less safe.” The Mt Xpress staffer who decided to attract attention to John Boyle’s excellent and well researched article posted under Community News on 4/19 almost forced me to steer clear of this article. Why was the word “perception” used to describe what the reality is concerning crime in downtown Asheville? It would have been a shame to have not read his very informative, comprehensive overview of the state of mental health in our area.