By Clarissa Donnelly-DeRoven, North Carolina Health News

This is the second story in a series examining how NC Medicaid’s Healthy Opportunities Pilot is going

What would it mean for a health care program to actually pay for the things that help people be healthy, instead of just paying for care once they get sick?

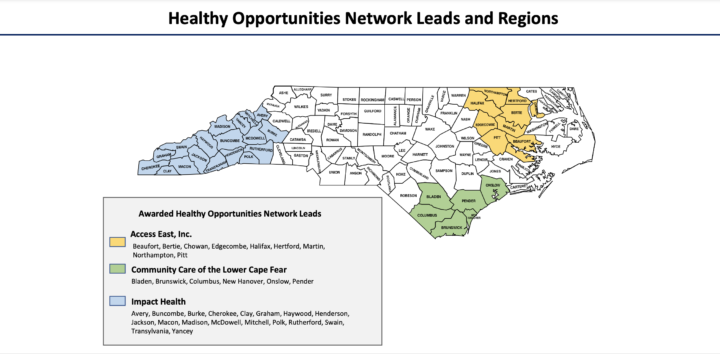

That’s what North Carolina’s Medicaid office started trying this past March when the program launched a first-of-its-kind program: the Healthy Opportunities Pilot, or HOP for short.

HOP’s aim is to see if the state can improve the health of patients on Medicaid by paying for non-medical things that might prevent them from getting sick — fresh produce, or first month’s rent, for example. These things are often called social determinants, or social drivers, of health.

“The last five years or so people and institutions, including national health policy and government bodies, are starting to recognize that social determinants of health actually play probably a larger role in health outcomes than than just medical care,” said John Purakal, an emergency medicine doctor at Duke who oversees a program that screens patients in the ER for unmet social needs and connects them to resources.

The care patients get in a doctor’s office obviously does impact them, but multiple studies show that what happens to patients outside of that medical visit — where they live, what they eat, who they spend time with — has a far greater impact on their health.

While some social problems, such as domestic violence, impact people across class lines, others are inextricably tied to and exacerbated by factors such as income or access to transportation.

That’s partly why offering these services to the low-income people on Medicaid holds such potential.

Since the program is the first of its kind in the country, some bumps and growing pains were expected. And to be sure, those participating in the pilot have documented plenty.

They argue that these issues shouldn’t cause panic, but also that revisions need to happen as quickly as possible, both so HOP can prove its worth and so people can get access to the care that they’re entitled to.

How does it actually work?

Case managers who work at one of the five insurance companies responsible for the majority of Medicaid beneficiaries act as the program’s gatekeepers. They identify someone with Medicaid who is “high cost,” meaning they’re using expensive services – such as the emergency room – a lot.

The care manager reaches out to that person and sees if they have one or more chronic health conditions (diabetes, substance use disorder, chronic heart disease, etc.) and one or more unmet social needs: Do they struggle to afford groceries? Are they having trouble paying rent? Are they afraid of somebody they live with?

If they answer yes to questions in both sets, they’re eligible for services provided under the HOP pilot. The care manager then refers that person to a nonprofit in their area, called a Human Service Organization, that offers resources to deal with whatever issue they have.

Unlike insurance companies, most of these local organizations have deep roots in their communities.

After the local organization has worked with that Medicaid patient, they submit an invoice to the insurer — as a health care provider would — to be reimbursed for services provided.

That’s the simplified version.

In reality, it’s a complicated web of entities with many steps and handoffs. Sometimes it works like a well-oiled machine, and other times it’s like there’s no machine at all, just a series of gears grinding against each other.

Money waiting for a client

Perhaps the most significant problem area, according to multiple human service organizations, is the referral process.

That’s the case in Madison County where there’s an affordable housing crisis, much like most of western North Carolina. The Community Housing Coalition of Madison County, a human service organization in the HOP program, conducts preoccupancy home inspections. They can also help pay for pest and mold removal, along with other critical repairs.

But, they haven’t gotten any client referrals.

“We have gotten a couple attempts at referrals, I guess, if you want to call them that,” said Leigh Waters, the client services coordinator at the organization, during the first week of August. They had to reject these referrals because although the people had Medicaid, they didn’t actually qualify for the HOP pilot.

“I definitely see the need,” she said, “and I also see on the other hand these funds that HOP does have and so it’s frustrating to know there’s money there that’s not being spent.”

Amy Upham, the executive director of Eleanor Health Foundation in Buncombe County, said her organization is seeing the same thing. The organization works with people who have substance use disorder and other mental illnesses and connects them with transportation, housing, affordable medications, employment and more. During their regular work each month, they get about 100 applications requesting various kinds of financial assistance.

Many of those folks are on Medicaid, and therefore eligible.

“We could potentially be serving 30, 40, maybe even 50 people a month who are on Medicaid, and we’re getting three referrals a week,” she said.

‘Passing the buck’

Waters explained that she’s met with a couple of people who seemed like they would be eligible for the HOP pilot, but she can’t actually enroll anyone in the pilot.

“Right now, the best that we can do is tell a client that we think may be a fit for the referral to call the number on the back of their Medicaid card, and hopefully get referred that way,” Waters explained.

“That itself is not the best way because we are dealing with the elderly population,” she said. Sometimes those clients can’t read the tiny writing on the back of their card — if they even know where their card is.

“If they have to be on a phone call for 30 minutes to an hour just to get to something, I think it’s probably hard for them to see the incentive in that phone call,” she said.

That chain of referral also touches on something else for Charam Miller, the director of the Macon Program for Progress.

“It feels like you’re turning somebody away when you say ‘please go ahead and call the number on the back of your card,’” she said. “It kind of feels like we’re passing the buck, and if somebody’s hungry or if somebody’s in need of services, I want to see that need met.”

Waters and leaders at other organizations said that sometimes when clients do call the number on their Medicaid cards, the person on the other end (who works for the Medicaid managed care organization) doesn’t know what HOP is, and sends the caller away.

“People have called their Medicaid line and they don’t know what they’re talking about at all,” Waters said. “And then [our clients] are like, ‘Why did you tell me to do this?’”

In a statement, Peter Daniel, executive director of the NC Association of Health Plans, which represents the Medicaid managed care companies at the legislature, said that all of the insurers worked closely with the state health department “to build processes and prepare their teams to generate and accept referral for HOP services.”

“Care managers and many other member-facing associates at the [Medicaid health care organizations] have been well-trained to identify members who meet the eligibility criteria,” Daniel said. “We recognize the opportunity for continued engagement with our delegated care management entities … in the education process so that they can better support our members in getting the services they need.”

Making the process smoother

Multiple leaders suggested that if the pool of people who could issue referrals expanded, the process might work better. If, for example, the process worked similar to the way it does at a doctor’s office: somebody comes looking for care, the organization determines that person is likely eligible for program coverage, the organization provides the needed service, and then the organization submits a request for reimbursement.

The state health department, which oversees the program, said they’re aware of these issues. But, they said their hands are tied because of the way the referral process was authorized in its federal Medicaid waiver — the document that enables the state to receive funding for the program.

“We are trying to implement a ‘no wrong door’ entry approach,” said Amanda Van Vleet, the associate director of innovation at NC Medicaid, who oversees the pilot. “What we’re really working on is getting [human service organization] providers in the pilot regions to really understand how to assess if that person may be eligible for the pilot, and then basically they connect [the client] to their care manager directly, since the care manager is really the entry point.”

All services through the HOP program require patients to be pre-approved for eligibility.

“And so it makes it hard for us to have a [human service organization] just give the services directly without getting that approval,” Van Vleet said. “Our understanding is that our waiver doesn’t really allow for that.”

She added that when somebody does manage to get a referral, the rest of the process goes pretty quickly.

“I think our most recent data shows that about 98 percent of enrollment and authorization requests are happening in under a day,” Van Vleet said.

Though the pilot requires a pre-authorization of services, the insurance company doesn’t have the same financial incentive to delay or deny care as it might in other circumstances.

“They don’t get to keep any service dollars that they don’t spend,” explained Julia Lerche, the chief strategy officer and chief actuary for NC Medicaid. That’s because the state distributes an allocation to each managed care organization monthly that they can only use to pay for services through the pilot. Any money they don’t spend can roll over into the next period, but at the end of the pilot they’d have to return any surplus.

Can brochures and flyers make the difference?

Another major issue, according to a handful of participating organizations, is that many people on Medicaid don’t know the pilot exists.

Van Vleet said the state has relied primarily on the health plans to market the program.

“Some of them are doing more proactive outreach to members through some additional channels, but that’s dependent on the health plan,” Van Vleet said.

Van Vleet said the state is brainstorming better approaches. One promising idea is to connect with primary care providers in pilot regions and tell them about HOP since those are likely trusted messengers.

In practice, much of the marketing of the HOP program falls to the human service organizations themselves.

The Macon Program for Progress, for example, has taken to putting up flyers on buses, libraries and in senior centers. Caja Solidaria, an organization in Henderson and Transylvania counties that delivers fresh produce, distributes brochures that describe the different services available in the counties, as well as the numbers patients can call to be enrolled.

Other organizations are giving presentations to local county or social service organizations, which also come into contact with potentially eligible people.

“I’m meeting with the health department in different capacities,” said Waters, from the Madison county organization that hasn’t gotten any referrals. “Hopefully reaching out to local organizations that way will get the word out more.”

A nearly 100-page document describes how the HOP program’s effectiveness will be analyzed, and some have expressed concern that if the program doesn’t get enough participants, the sample size will be too small for there to be an effective evaluation.

“Given the estimates that we have on the potential number of enrollees in the pilots and what we would need for the evaluation, we should have enough enrollment,” Van Vleet explained.

“That said, we’re keeping an eye on it closely.”

This article first appeared on North Carolina Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.![]()

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.