In the early months of 1964, residents shared their thoughts on the impending civil rights bill. Most who offered their opinions expressed a dire message of inevitable chaos if the measure were to become law.

In the early months of 1964, residents shared their thoughts on the impending civil rights bill. Most who offered their opinions expressed a dire message of inevitable chaos if the measure were to become law.

The route through the Swannanoa Gap — where present-day Old U.S. 70 and Mill Creek Road intersect — was first carved out by Archaic Indians as they came up out of the Appalachian foothills and followed Swannanoa Creek on the way to hunting and gathering opportunities in the mountains. Later, Buncombe County’s first white settlers climbed through the gap as they moved into the area. Historian Dan Pierce shares the gap’s history and culture, as well as suggestions for exploration.

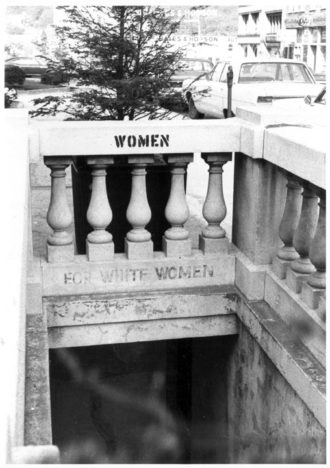

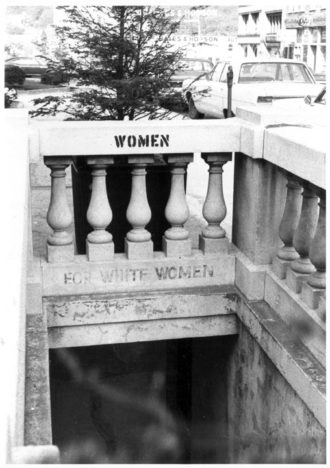

Vance, Patton, Woodfin, Henderson, Weaver, Chunn, Baird — their names are familiar to anyone living in Asheville and Buncombe County today. All were wealthy and influential civic leaders. They were also major slaveholders or slave traders and white supremacists.

The Buncombe County Board of Commissioners remained divided along partisan lines. Chair Brownie Newman and his three Democratic colleagues voted for the removal of Confederate monuments at Pack Square Park and the county courthouse, as well as establishing a task force on the Vance Monument, while Republicans Joe Belcher, Anthony Penland and Robert Pressley voted against those moves.

Originally celebrated almost solely within the African American community, interest in the observance of the end of the institution of slavery in the United States is on the rise, with two events planned in Asheville for June 19.

“Plainly and unequivocally, common sense says keep the slave where he is now — in servitude,” declared Zebulon Vance, in a May 16, 1860 address to the House of Representatives.

In 1948, amid a growing polio outbreak, city residents contributed what they could to the Asheville Orthopedic Home, a local health center that cared for the region’s infected children.

Richie Tipton, Jeff Anders and the late Rocky Lindsley delve into Asheville’s formative rock years with help from fellow musicians who shaped the scene.

Asheville City Council unanimously adopted a joint resolution with Buncombe County to remove two Confederate monuments at the Buncombe County Courthouse and in Pack Square Park. The resolution also convenes a task force to further explore the removal or repurposing of the Vance Monument in downtown Asheville.

In July 1948, as the number of polio cases and related deaths increased in Asheville, the city’s health department began enacting orders to limit social gatherings. Initial ordinances were directed at Asheville’s youth. But by month’s end, the entire city was subjected to new mandates.

In June 1948, four Buncombe County residents were diagnosed with polio. At the time, there was a growing concern about a possible statewide epidemic. Worried parents bombarded Asheville’s health officials with phone calls, convinced that these local experts were underreporting the true number of cases in the city.

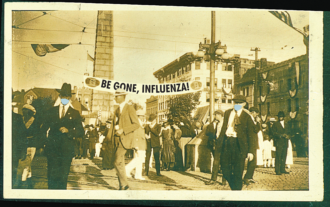

As 1920 began, so too did the city’s latest bout of influenza. An initial six cases quickly skyrocketed to 232. Once again, the city was confronted by a highly contagious virus that needed to be curtailed.

In his latest book, “They Were Soldiers: The Sacrifices and Contributions of Our Vietnam Veterans,” local author Marvin J. Wolf interviews 48 Vietnam veterans, including Oliver Stone and Colin Powell, about their lives after the war.

In January 1919, Buncombe County reported 141 new cases of the influenza over a 72-hour period. In response, Dr. Carl V. Reynolds, the city health officer, announced a new ban on social and fraternal gatherings. Displeased residents spoke out against the latest safety measures.

Recognizing the historic significance of COVID-19, local archivists discuss ways to record the moment for future generations. They also offer guidance for those looking to better organize their family documents during the “stay home, stay safe” mandate.

Throughout November 1918, local health officials and residents continued their efforts to contain the spread of influenza. But as December neared, the city seemed eager to get back to business as usual, despite the risks involved.

In the midst of the 1918 influenza, one local resident attempted to use the health crisis to aid his legal defense.

“All hail to this new movement known as woman’s suffrage!” wrote one enthusiastic Asheville resident in a letter to the editor, published on Nov. 23, 1894.

“Why should North Carolina be behind in forming woman’s suffrage organizations?” asked local Asheville resident Helen Morris Lewis in a Nov. 15, 1894, address to fellow community members.

In a Feb. 3, 1916, editorial, The Asheville Citizen declared: “Public opinion is an irresistible force, and sooner or later it will banish the blight of child labor from American soil.”

In early 1967, the threat of increased property taxes initially delayed the East Riverside Urban Renewal project. By year’s end, the prospect of losing $6.3 million in federal funds led city residents to a change of heart.