ASHEVILLE, N.C.— When a longtime member of Nazareth First Missionary Baptist Church gets together with the congregation’s long-serving pastor to discuss the institution’s 150th anniversary this year, the conversation takes a distinctly nostalgic tone.

In Asheville’s historically African-American East End neighborhood during the 1950s, “You knew everyone who belonged to Nazareth, you knew everyone who belonged to Mount Zion,” recalls the Rev. Dr. Charles R. Mosley Sr. “They were the two dominant congregations.” On Sunday mornings, he says, the whole community took to the streets, walking to the different houses of worship.

But in the wake of urban renewal in the 1960s and the more recent threat of gentrification, he continues, “I don’t know of any congregants in the neighborhood now.”

Mosley, who moved to Asheville during middle school and graduated from Stephens-Lee High School, has led the church for 43 years. “I had no idea I would be here this long,” he says.

These days, Nazareth Baptist’s 50 or 60 remaining members drive from other communities around Asheville to attend services and activities. The imposing brick structure topped with a tall copper-clad steeple still resounds with traditional hymns every Sunday morning, but an aging membership and an influx of new residents to the neighborhood point to an uncertain future.

On Friday, Oct. 20, the church will celebrate its 150th anniversary with a banquet that’s already sold out. The keynote address will be delivered by Asheville native James Ferguson, a notable civil rights attorney who now lives in Charlotte. On Sunday, Nov. 12, the church will welcome the public to morning and afternoon services to mark the milestone.

Legacy of slavery

“It started with Miss Mary Patton, who was a white lady,” explains church member Pat Griffin. “It was she and her father that took an interest in the black community. He was … Captain Tom Patton.”

Mary Patton’s Sunday School, Griffin says, began in 1862 with classes in the Pattons’ home in the Beaverdam community. After the end of the Civil War in 1865, the classes moved downtown to the First Baptist Church.

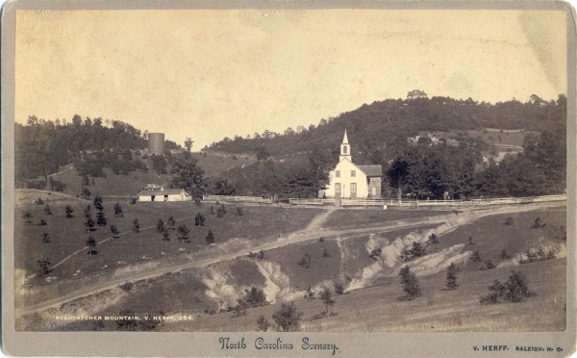

However, by 1867, continues Griffin, “The whites wanted the blacks to have their own church.” Thomas Patton donated land on what was then called “Chinquapin Ridge” to the African-American members of First Baptist. The site lay just uphill from an area where people enslaved by the Patton family had lived for years.

According to an Oct. 1, 1967, article in the Asheville Citizen-Times, congregants of the new church soon began working to construct a log building on the site. “But their first place of worship was an arbor made of brush cut from trees needed in the log structure,” the article states. A church bell hung in a tree. The Rev. Caleb Johnson was the first minister. “Rev. Otis E. Dunn, the one that I succeeded, had the longest tenure, which was 26 years,” says Mosley.

The current church building is only the latest to occupy the site; previous buildings fell victim to fire. “The church prior to this building, it was just beautiful,” Mosley recalls.

Before the fall

In his youth, Mosley says, “The church was the center of the black community. Practically everybody that lived in the neighborhood, you chase their history, and it will go back to Nazareth or Mount Zion [Missionary Baptist Church] or St. James [AME Church].” People sorted themselves by class, he recalls: “The professional blacks, they mostly attended Hopkins Chapel AME Zion Church and Berry Temple [United Methodist Church]. The working class, they went to Mount Zion and Nazareth.”

In the East End, as in other African-American neighborhoods, churches stood alongside family homes. “They would meet each other on the street, walking, from one church to the other,” Mosley remembers.

After graduating from high school in 1957, Mosley left Asheville to continue his education at Shaw University in Raleigh. He returned in 1975 to find the African-American community devastated by urban renewal. “It disintegrated, it just scattered the neighborhoods,” Mosley says of the government’s actions. “They were in the process of tearing down Stephens-Lee when I got home,” he remembers. “I got one of the bricks.”

Many former residents of the East End moved to Shiloh, Arden and West Asheville, Mosley says. “It was black removal, that’s exactly what it was.”

“The black community didn’t know what was happening. It was like we were sleeping, and all of a sudden you woke up and everything was different,” Griffin remembers. “The close community that was in those locations, it wasn’t there anymore.”

Resilience

Despite the trauma and disruption of urban renewal, under Mosley’s leadership, Nazareth continued to thrive. In addition to the church’s strong membership base, Mosley says, “We used to have organizations, and that helped to keep the church knitted. The Progressive Club and the Vineyard Workers were the two major clubs in the church who raised money, who had programs, special projects, and who gave sacrificially.”

In recent years, however, “The church has stood, but many of our people have died or changed locations,” says Mosley. “You don’t have the neighborhood cohesiveness that the older congregation had. Houses change almost weekly or daily.”

Griffin concurs, “Those of us who are there now are driving from different parts of Asheville.”

Nazareth also is dealing with changing cultural expectations and competition from newer churches. While he views himself as a staunch traditionalist, “There are other groups with a different approach to praise and worship who are drawing our young people,” Mosley says.

“See, young people, they go to churches where you can hardly identify it as a church,” Mosley explains. “It’s more like they’re clubbing. But they call it worship. And that’s what attracts them.”

Still, dedicated members like Griffin help to keep church life vibrant. In addition to Sunday services, Nazareth members engage through weekly Bible study classes, choir, Women’s Day and Men’s Day events, a hospitality ministry, a senior care program and ad hoc committees like the group coordinating the church’s anniversary events.

The church’s youth department is working to bring more young people into the fold. That initiative gives Mosley hope, “because reaching young people is where the history will expand and explode and have merit in years to come,” he says.

When asked what he most would like people to know about Nazareth, Mosley says, “We are open to the entire community.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.