Ever since the first humans ventured into the valleys and hollows of what’s now Western North Carolina, they’ve had to contend with the Southern Appalachians’ forbidding terrain and the resulting isolation. Over time, the various groups that inhabited the area learned to subsist on what was available to them in the surrounding wilderness, often drawing on traditions handed down from their ancestors. And as European settlers developed agrarian communities, barn design and usage came to symbolize the evolving efforts to carve out an existence here.

Shelter on the Mountain: Barns and Building Traditions of the Southern Highlands, an exhibit at Mars Hill University’s Rural Heritage Museum, traces the evolution of local building practices. Beginning with the Ani Katuah, or Cherokee, people, it continues through the coming of European settlers and the rise and fall of tobacco as a staple crop. At every step, the show illuminates the ways that barns and other structures have reflected the cultures that produced them.

Madison County alone is home to more than 10,000 barns, many of them facing an uncertain future, and the curators hope this exhibit will shed light on these structures’ place in the relationship between WNC’s inhabitants and the mountains they call home.

Agrarian heritage

“I’ve always loved old barns,” says architect Taylor Barnhill, who moved to Madison County nearly 40 years ago. “When I moved up here, I made a point of learning the culture and the building traditions,” notes Barnhill, the lead researcher for the Appalachian Barn Alliance.

The alliance was formed in 2012 when Ross Young, who heads the Madison County Cooperative Extension office, got together with other residents concerned about documenting and preserving the region’s agrarian heritage. Barnhill was eager to help. “We began talking about a possible exhibit a couple of years ago,” he recalls. “It was just a natural fit for the Rural Heritage Museum.”

Les Reker, the museum’s director, also serves on the alliance’s board. The exhibit, he says, is “about more than just Appalachian barns of the 19th and 20th centuries. We’re telling the story of the built environment in the mountains.”

Native ways

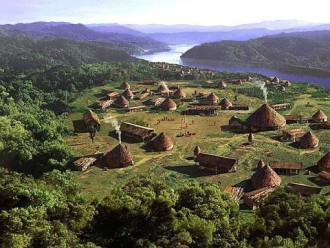

That story begins long before the first Europeans even laid eyes on the Blue Ridge. The precursors of the Ani Katuah lived along the French Broad and Catawba rivers, and Shelter on the Mountain draws on early accounts as well as archaeological evidence to imagine the kinds of structures erected by those first inhabitants.

“These people arranged their environment for themselves for many reasons, whether ceremonial or for living,” says Reker. The early explorers, he continues, found arranged rock formations and pictographs like those at Paint Rock, near Hot Springs, but “No one knows the purpose. The Cherokee don’t know; no one does.”

Ani Katuah “barns” often consisted of poles driven into the ground and walled in with wattle and daub, with roofs of thatch or bark and raised floors to keep rodents and moisture away from the grains stored within. “It’s kind of a universal structure,” notes Barnhill. “You would find those in just about any culture in the world that you look at.”

Those barns are long gone, of course, but archaeologists, he says, “are looking for the stained earth where those posts were set in the ground. That stain stays for hundreds to thousands of years; that’s how they determine where a settlement was.”

The white man cometh

Early European incursions brought new ideas and building designs to the region. In the 16th century, the expeditions of Hernando de Soto and Juan Pardo explored WNC, and Pardo established the area’s first European forts. By the late 18th century, Scots-Irish and English homesteaders had begun carving out settlements, using whatever materials were at hand.

Stone was familiar to many settlers, says Barnhill. “If you look at Scotland, Ireland and England, they had already cut over all their forests, so they built things out of rock. Obviously, there was lots of rock here.”

Evidence of early stonework can still be seen in Madison County. Near Hot Springs, for example, stands a barn with a 2-foot-thick stone foundation; Barnhill believes it may be the original base of William Nielsen’s barn, built in 1800. “You also come across these stone walls — not as many as you see up in New England, but occasionally you see a thick stone wall they used for fencing in animals.”

From forest to farm

By the mid-1800s, however, most mountain structures were made of hewn logs laid on their side and notched in the corners, reducing the need for nails. The abundant ash and chestnut trees were a readily accessible source of building materials for settlers as they cleared land for farming purposes, says Barnhill. Often, the structure’s lower level housed livestock, with hay and grain stored up above.

The logs used for these early barns could be up to 30 feet long and weigh 2,500 pounds, says Reker. “It was like building the pyramids!” he exclaims, “and it’s right here, in the history of this area.”

Settlers had to rely on their neighbors for help, so communities developed their own barn designs. “They’d have regions of the Southern Highlands where a certain kind of barn would appear, and then a couple mountains over, it’d be something else. They all influenced one another,” says Reker.

The exhibit also features the myriad tools — often handcrafted by settlers — used in construction and daily farm work. “You might have blacksmiths do the forging, but people for the most part hewed their own wood” for these tools, he says, adding, “Everything emanated from the forest.”

In the mid-19th century, encroaching outside influences began bringing other building ideas to popular tourist locales like Hot Springs. Grand hostelries such as the Warm Springs and Mountain Park hotels, says Reker, “were independent of the log tradition, though this was being done at the same time as the barns.”

Access to sawmills, bricks and other modern building materials from Tennessee spurred further development and helped make Hot Springs “an oasis for the wealthy in the wilderness” before and after the Civil War. Amenities such as one of the region’s first golf courses drew affluent vacationers and the political elite, notes Reker, “and, of course, folks came for the springs. It was the resort to go to in the Southeast.”

New dimensions

The arrival of the railroad in the late 1800s further opened up the mountains to the outside world and revolutionized both farming and construction in the Southern Appalachians (see “Coming Round the Mountain: Rural Heritage Museum Opens WNC Railroad Exhibit,” July 1, 2015, Xpress).

Portable sawmills created new options for construction. “People would travel around with the sawmills, set up shop, and [residents] would bring their logs there,” Reker explains. It was slow going — producing a few pieces could take an entire day — but dimensional lumber enabled locals to add a little flair to their barn designs.

One example is the emergence of cantilevered barns, which feature an overhanging roof that’s not supported by columns or posts. Some barns, Reker reveals, “were actually cantilevered on both sides. I’ve asked why they did that, and the answer is because they could. It was kind of showing off, in a way.”

Dawn of the golden leaf

The introduction of tobacco cultivation wrought more profound changes. Beginning with a wartime agricultural stimulus program instituted by Abraham Lincoln in 1862, tobacco from Virginia was brought in during Reconstruction to help rebuild the shattered mountain economy.

By the dawn of the 20th century, tobacco had taken hold as the main crop in the mountains. Madison County, for example, became the state’s leading producer of flue-cured tobacco and, later, burley tobacco, says Barnhill.

“They had to have a different type of barn, because it had to be heat-cured,” he explains. “It’s still a log barn, but it has a square footprint: It’s very tall, and the spaces in between the logs were chinked with mud, like log cabins. They would hang the tobacco inside the barn, and afterward would build a rock furnace on the floor and keep a fire going to heat the barn and dry the tobacco.”

The new design and the access to modern building materials led many farmers to opt for gently pitched, metal gambrel roofs rather than the steep, wood-shingled roofs they’d previously used to funnel water and snow off quickly and deter rot, Reker explains.

The introduction of the less-labor-intensive burley tobacco from Kentucky, and the passage of the Agricultural Adjustment Act under President Franklin Roosevelt in the 1930s, cemented tobacco’s role as WNC’s primary economic driver for the rest of the 20th century. (See “Smoke and Mirrors: the Death of Tobacco in WNC,” Feb. 25, 2016, Xpress.)

Honoring the past

The fortunes of many local farms, however, took a drastic turn with the passage of the 2004 Fair and Equitable Tobacco Reform Act, which ended the New Deal-era quota system. And with tobacco now less lucrative, many historic barns across Madison County and WNC began to fall into disrepair.

“We’re losing them all the time to the environment,” says Reker. “It’s the story of farming in America: The people who own that property are usually older couples who aren’t farming anymore, and they don’t have the funds to keep up their barns.”

Thus, he maintains, the efforts of the museum and the Barn Alliance to document these structures are a key to preserving the region’s agrarian and cultural heritage. “The mountains enhanced this idea of individualism and independence, living separate from everything else. That’s why the people here differed from everyone else in terms of their response to the Civil War and a host of other changes in the country.”

Barnhill also hopes that highlighting mountain people’s ingenuity will help dispel negative stereotypes about Appalachian culture. “Mountain culture is all about having the hope that something can eventually be reused, rather than going out and paying good money to buy something new,” he says. “There’s a lot to teach the rest of the country when it comes to taking good care of your tools, your barns, your vehicles.”

Shelter on the Mountain: Barns and Building Traditions of the Southern Highlands will be on display at the Rural Heritage Museum through Sunday, May 28. The museum is open Tuesday through Sunday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Admission is free. For more information, call 828-689-1400, or visit mhu.edu/museum. To learn more about the Appalachian Barn Alliance’s work, including their historic tours, visit appalachianbarns.org.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.