Over 30 years with the U.S. Forest Service, a master’s degree in urban forest ecology and arborist certification from the International Society of Arboriculture have taught Ed Macie quite a lot about trees. Yet when the Asheville Tree Commission member is asked to boil down the wisdom gained over his long career, he presents a single sentence of stark truth: “Trees can’t run away from bulldozers.”

Asheville, Macie argues, is living proof of that statement. Over the last decade, the city has been transformed by a construction boom and human population growth of at least 10 percent. At the same time its tree canopy — the area covered by leaves, branches and stems when viewed from above — has decreased by approximately 8 percent.

This canopy is a resource that Asheville can ill afford to ignore, says Stephen Hendricks, chair of the Asheville Tree Commission. “As a city starts to lose its tree canopy, all kind of effects come into play: stormwater problems, heat problems, air pollution. You lose aesthetic appeal and a sense of place as well,” he explains. “The city is developing really rapidly, and we’re a little bit late to the game.”

In January, Hendricks and the members of the Tree Commission submitted a series of goals to help Asheville catch up in protecting its canopy. By adding a dedicated urban forester, crafting an urban forest master plan and strengthening the current municipal tree ordinance, they say, the city can manage its growth in a greener and more climate-resilient way.

“The more hard surface we have, the more green we need to balance it out,” Hendricks says. “When you think about all the great cities of the world, the reason they’re great cities is because they built in green space along with dense development.”

Forester for the trees

Asheville’s government manages all trees on its property and rights of way through the Public Works Department. City Arborist Mark Foster coordinates the care of those trees, but no single city staffer is charged with protecting trees on private property, where the majority of canopy loss and preventable damage occurs. Hendricks says an urban forester would fill that crucial planning gap.

“We have the city arborist, who’s very good, but he has his hands full keeping a crew on board and going around just doing the very basic stuff,” Hendricks says. “The reason we need an urban forester is to put the big picture together.”

Public Works Director Greg Shuler says that the new position will be requested in the next fiscal year’s budget under the Development Services Department, which interacts regularly with private developers. He estimates the upfront cost of adding an urban forester at $104,205, which includes a new vehicle and computer, and the ongoing cost at $70,035.

Shuler agrees that the new role would add expertise that the city does not now possess. “In very general terms, an arborist is trained to focus on the health and well-being of a tree, while an urban forester is more focused on how the trees in a forest interact with one another,” he explains. “[Foster] is an experienced and effective arborist who has the skill set to evaluate a broader perspective than a single tree, but it’s really outside of his formal training.”

Taking such a holistic approach would encourage the city to see its urban forest as valuable “green infrastructure,” says Hendricks. With their deep root systems and extensive water use, he points out, trees help mitigate flooding and erosion from storm events and reduce the need for sewer expansion.

Trees also sequester carbon and reduce energy use by shading buildings, Hendricks adds — functions that support Asheville’s “Climate City” aspirations. “To be climate-resilient like it wants to be, the city is going to have to start valuing its canopy. In other words, it’s going to have to regreen and regain some of that canopy,” he says.

What’s the plan?

In addition to his or her regular duties, the urban forester would help Asheville develop a new urban forest master plan, which would include updates to the city’s existing tree ordinance. Shuler says that next year’s budget contains a one-time request of $250,000 to hire consultants to assess the ordinance and formulate a plan.

It’s a step Macie welcomes, but he expresses some frustration that Asheville has taken so long to create such a document. “The one most important single thing we don’t do that other cities do is protect trees. There’s nothing in our policy,” he says, calling the city “probably 25 years behind” other progressive municipalities across the southern U.S.

Asheville’s tree ordinance, last revised by City Council in 1997, does call for the creation of a master street tree plan as the responsibility of the parks and recreation director, a post held by Roderick Simmons since 2007. Simmons was traveling and could not be reached for comment by Xpress’s press deadline, but Shuler confirmed that, to his knowledge, city staff had not previously requested any funding to fulfill this mandate.

Shuler did not provide any explanation for why Asheville had not yet developed the plan, saying that the tree ordinance predated his time in city administration. “Our city currently has many master plans and ordinances that specify actions and initiatives that aren’t funded. This funding request is a step to fully fund this particular plan,” he said.

Asheville identified the need for an urban forest plan two to three years ago, Shuler continued, and laid its groundwork by conducting an analysis of the city’s tree management programs and a formal canopy study. “With the rate of development being as it is, city staff and the Tree Commission identified this path to get to the realization of the plan identified in the Code of Ordinances,” he said.

A set of 11 recommendations proposed by the Tree Commission outlines key points for the plan. These include a new no-net-loss canopy policy, a “protected” definition for specific trees on both private and public property, minimum canopy standards for different land use types and the inclusion of prohibitions on invasive species in city standards.

Arboreal advocates

At least one member of the Tree Commission, however, isn’t waiting for the city to enact its master plan. “We have certain local circumstances that we need to address, and things are happening at a rate where going through the political system just takes so long — longer than we have,” says commission member and Asheville GreenWorks Executive Director Dawn Chávez.

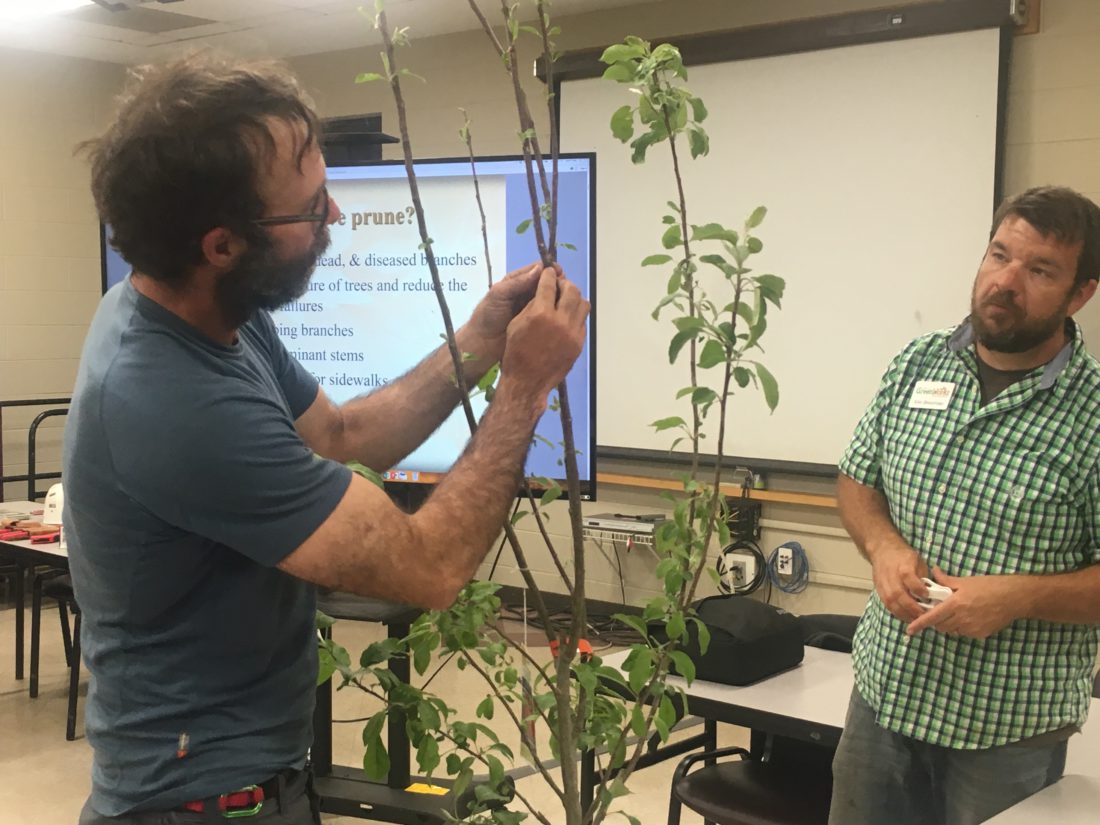

To that end, GreenWorks has launched a series of free weekly workshops aimed at empowering citizens to become grassroots advocates for urban trees. Participants learn skills such as tree planting, pruning, maintenance and protection during construction projects.

“In Asheville, being such a green city that has so many residents concerned about the environment, most people assume that we have tree protection ordinances in place and are surprised to find out that we don’t,” says Chávez. “Short of an ordinance, we figured building public awareness and public will for protecting trees is the best way to go.”

GreenWorks is also certifying those who complete a six-course curriculum as “Neighborhood Tree Keepers.” These community members, Chávez explains, can serve as resources for concerned neighbors and advise property owners about best practices for tree preservation during development. Additionally, they will be eligible for $500 mini-grants from GreenWorks to fund tree-related community projects.

Macie, who is teaching a class about tree protection in Asheville on Tuesday, March 26, says he hopes participants come away from the workshops able “to have intelligent discussions about trees.” Whether they’re talking with a small-scale developer or City Council, he says, informed citizens can help decision-makers understand their options around trees.

Speed of life

Although he remains hopeful about the city’s potential for urban forestry, Hendricks agrees with Chávez on the urgency of the situation. “This is the time for the city to act, because 10 years from now, if we keep acting like we are, it is very hard to go back and retrofit green space and canopy,” he says. “You’ve got to have a policy in place.”

Macie acknowledges that the Tree Commission’s request comes at a time of budgetary stress for City Council. Asheville’s government faces $270 million in unfunded capital projects through fiscal year 2024, and economic growth has placed upward pressure on salaries and contract costs. But for him, preserving the urban canopy is a matter of seeing the bigger picture.

“When you change the character of a community, you might also change the interest of the tourists that are coming. … If we change what the city is in terms of its aesthetic appeal, which is another benefit of trees, we may lose it,” Macie points out. “I think the health and livelihood of the tourism industry is dependent on how the city looks.”

And Hendricks suggests that the green infrastructure benefits of urban trees will pay for themselves over time. “Would you rather see green spaces, or would you rather put your money into pipes in the ground?” he asks. “It’s not that hard a choice.”

Here’s yet another frivolous, $35 per hour, position request from the City. This one will tell you what you can and cannot do with your own trees on your own property. I’d rather the City got off of their current spending spree and focused on providing priority services.

Specifically, I’d rather have workers who will address the backlog of work that’s needed rather than this invented need. I think Mr. Shuler was quoted in an earlier MtnX article that his department had a crazy amount of needs that were pushed out because the City couldn’t afford to address them. Among those needs were a lack of staff to do tree work on City trees.

It’s amazing how long it takes to move the ball on City policy. As Council liaison to the Tree Commission for eight years, and a voting member of the Commission for just over a year, I have been a first-hand witness to the slow pace of regulatory change regarding trees in the City. In part, all cities in NC are limited by prohibition enacted from Raleigh, but resistance has also been local. A glaring example is the City’s “recommended species” list—simply a list of suggestions for property owners and developers as the best options for planting. When arborists on the Tree Commission sifted through the old list and found numerous UNDESIRABLE species, getting those changes into a revamped list was like pulling teeth without novocaine.

I hope our current recommendation will be enacted during this budget cycle. Being one of the first Tree City USA members, we ought to have done more to protect our canopy ages ago.

Thanks for sharing. Its really Informative.