Executive Order 80, enacted by Gov. Roy Cooper in October, was meant to announce a major shift for North Carolina. As the only executive order that Cooper “has personally and publicly signed,” according to the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality’s Sushma Masemore, the document signaled the governor’s particular urgency in transitioning the state to a clean energy economy and addressing climate change. Its objectives include reducing North Carolina’s greenhouse gas emissions to 40 percent below 2005 levels, registering at least 80,000 zero-emission vehicles and cutting energy use by 40 percent in state buildings by 2025.

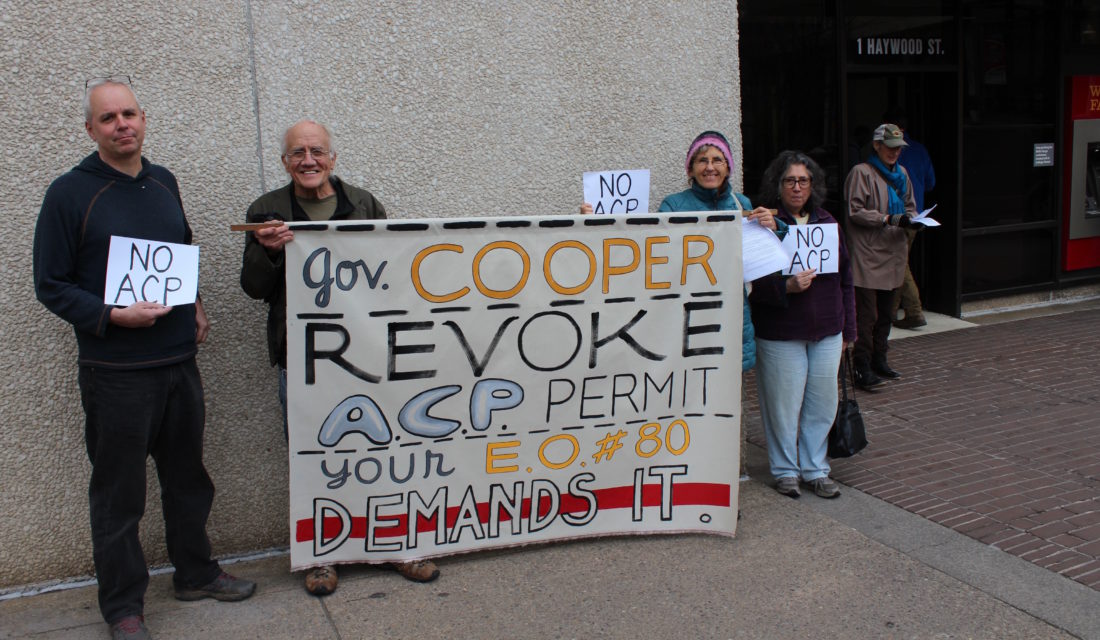

But during a March 14 listening session at The Collider in downtown Asheville about the DEQ’s Clean Energy Plan, a key provision of Cooper’s order, many of the roughly 70 Western North Carolina residents in attendance expressed frustration that the state wasn’t doing enough. Before the conversation even began, protesters with the Mars Hill-based Alliance to Protect Our People and the Places We Live unfurled a banner calling for Cooper to revoke a state permit issued under his administration for the Atlantic Coast Pipeline.

The ACP, which is not mentioned in the executive order, would create a new route for an estimated 1.5 billion daily cubic feet of natural gas from West Virginia through eastern Virginia and North Carolina. Activist Steve Norris said that the project would increase annual global greenhouse gas emissions by more than 12 times the savings projected to result from EO80.

Other commenters raised concerns about the basic assumptions of the executive order, which Masemore said will consider “market drivers” and the economic feasibility of clean energy alongside environmental and climate concerns. Ned Ryan Doyle, Technology Working Group co-chair for the joint Duke Energy/Asheville/Buncombe County Energy Innovation Task Force, said “the mentality that only short-term profits matter” is a major hurdle to progress.

“There’s no full-cycle accounting for the actual costs and benefits of clean energy versus the way the system is right now. It’s very broken up; it’s just not the right way to do the math,” Doyle said. “When that is how all of this is worked out — how [utility companies] are going to make a return on their investment, without full-cycle accounting — that’s a barrier to moving forward.”

Masemore said her team would relay the crowd’s concerns back to Raleigh but encouraged them to “think about pragmatic and practical solutions” for clean energy. “If you want a dramatic change overnight … all the things that need to line up in order to make that effect will take time,” she said.

Phoning it in

The clearest expressions of the audience’s displeasure with the status quo came through a series of live polls conducted via text message. Nearly three-quarters of those in attendance, for example, disagreed that the state’s current electricity system “supports the procurement of clean energy from a regulatory/utility business model perspective.” Only 9 percent strongly agreed with that statement.

“The ways that we have procured our energy up to now have not been clean for people who live next to coal ash plants or who live near smokestacks. The business model has not taken those externalized costs into consideration,” explained one attendee about her vote. “The regulatory agency that is supposed to look into the business model of our public utilities has consistently failed to do that in a rigorous way.”

Only 3 percent of attendees strongly agreed that the state gives customers “options for controlling their energy use and the source of their energy,” while 76 percent disagreed, with one commenter remarking that the question unfairly combined two topics. Asked if North Carolina’s electricity system “suitably addresses equity concerns,” 82 percent responded that it does not.

“From the fracking fields that feed the gas plants to the mountaintop removal sites that feed the coal plants, [the system] disproportionately impacts low-income folks and communities of color,” commented an attendee.

DEQ employees responded that the Asheville crowd was not alone in its critiques. “What we’re seeing so far is very similar values across the state,” Masemore said about previous community input sessions in Charlotte, Hickory and Raleigh. Climate and equity, she noted, were “at the top” of citizen concerns.

However, Masemore added that the legislation regulating the state’s power system specifies “adequate, reliable and economical” service — not environmental protection — as the goal of public utilities. Larger shifts of the system’s priorities, she said, would likely require legislative action by the General Assembly.

Value propositions

Compounding the challenge, Masemore explained, is North Carolina’s outsized appetite for power. Although ranked eighth in the nation in terms of electricity generation, she said, the state must import additional power equal to 10 percent of its own production to meet its needs.

That demand, Masemore said, means additional burning of gas or coal. While the continuing development of utility-scale solar and wind will make clean options more viable, she continued, “we don’t have an ability to bring in internal energy resources to generate our own power” at the current time.

Pauline Hannemann, co-founder and principal consultant at Aasha Advisors, suggested that the conversation about economic feasibility was rooted in the priorities of utility companies and their investors. Several audience members applauded when she called the DEQ’s input session “still stuck in the old thought process” and urged those in attendance to ask new questions.

“We have to put social first: our community, our safety, our health,” Hannemann continued. “Those things have to come first, or 30 years from now people will be wondering, ‘What the heck did they do?’”

Masemore noted that the DEQ has discussed the role of environmental benefits with the N.C. Utilities Commission as the body regulates power production in the state. However, she added, “it’s a continuing dialogue in their interpretation of the statute.”

Pace of progress

The Clean Energy Plan itself will come together on a relatively fast timeline. Masemore explained that most other states take two to three years to develop similar plans, but Cooper’s executive order calls for receiving a final version in October.

Public input opportunities will continue through July, with another Asheville listening session scheduled at The Collider on Wednesday, June 5, from 1-3:30 p.m. Individuals and organizations can apply to participate in facilitated workshops about the plan in Raleigh, and all North Carolina residents can provide public comment on the DEQ website (avl.mx/5tv) through July 31.

“We can’t tell you exactly how we’re going to use this at this time,” acknowledged Lori Collins, a consultant working with the DEQ, about the public input. “This is a guidance to help us understand where our constituencies are coming from, what’s going to bubble to the top.”

Near the end of the discussion, one commenter suggested that North Carolina’s legislators should be listening to the clean energy demand just as closely as its regulators. “I think we have a majority of people in this country who want a paradigm shift, and they want a paradigm shift rapidly,” she said. “We have to have democracy and money out of politics and people in power who represent those of us who want this.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.