Early voting for the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners primary starts April 24 — just two days after Earth Day. The juxtaposition underscores the fundamental link between sustainability and politics.

The county’s 2012 sustainability plan sets few specific targets, contains no enforcement provisions and includes no dedicated funding mechanism (see “Thinking Big”). In other words, unless the commissioners approve a particular initiative and agree to fund it, the plan’s broad language won’t necessarily get translated into concrete action.

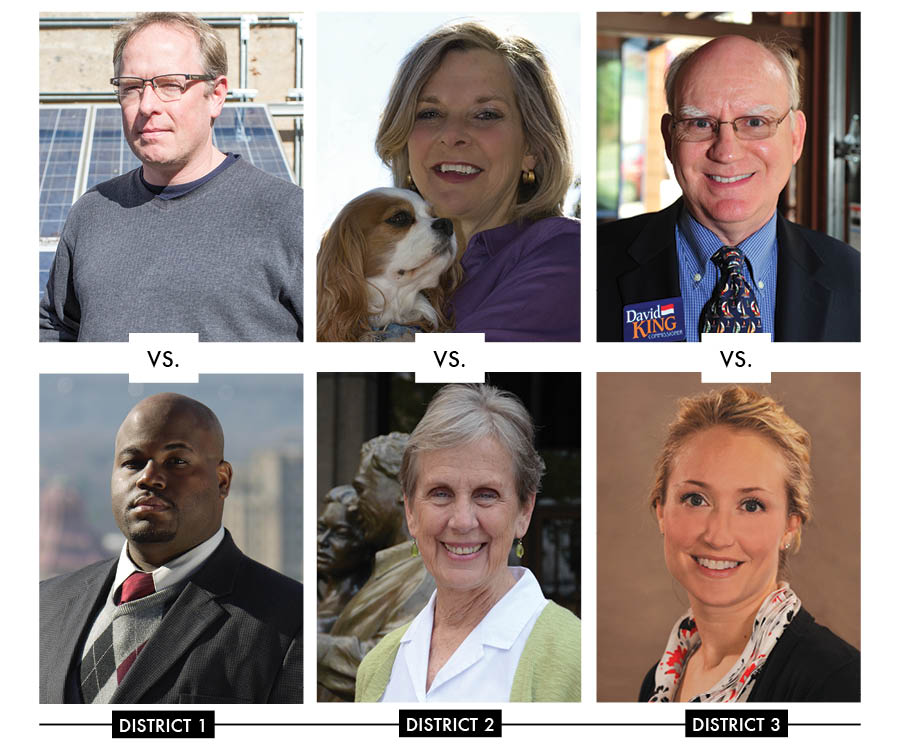

Against that backdrop, the upcoming primary looms large. Although the plan was unanimously approved in 2012, a new district election system that took effect later that year resulted in an expanded and more polarized board whose members may differ sharply when it comes to approving specific measures — and their price tags.

At the same time, several candidates seeking to unseat current commissioners are emphasizing things like affordable housing or cutting taxes rather than environmental issues. And with no Republican candidate in District 1 and no Democrat in District 3, whoever wins the primary in those races will likely be assured a seat on the board. Meanwhile, Republican Christina Merrill, who lost to Ellen Frost in 2012 by a mere 18 votes, looks to mount a strong challenge to whichever Democrat wins the District 2 primary.

Thus, the upcoming election gives local voters a chance to help shape the county’s sustainability policies for years to come.

Differing priorities

Last year, Commissioner Brownie Newman crafted the most significant environmental initiative of the board’s current term. Approved Dec. 3 on a 5-2 vote, it calls for reducing carbon emissions generated by county operations by 2 percent a year until the 2013 levels have been cut by 80 percent. Finding ways to meet that lofty target is now his “No. 1 goal,” says Newman, who represents District 1, the most liberal area of the county.

As a start, the county plans to spend $846,900 over the next five years implementing the recommendations in last year’s environmental audit. According to consultant Shaw Environmental, updating heating systems, lighting and other components of government buildings will save the county an estimated $173,500 annually. The precise impact on carbon reductions has not been determined.

Making the emissions target an even greater challenge is the fact that county operations are continuing to grow even as attempts are made to shrink the carbon footprint. In 2006, for example, county operations produced about 23,400 metric tons of carbon, according to General Services Director Greg Israel. Since then, the county has installed energy-efficient windows in the courthouse and added alternative-fuel vehicles to its fleet, yet due to expanded facilities, last year’s total was roughly 29,600 metric tons, says Israel — a nearly 27 percent increase.

Going forward, notes Newman, “Making sure we allocate the resources so [the plan] can be executed is very important.” To make real progress, he believes the county needs to follow the city’s lead and hire staffers who are “really focused on pursuing these goals.” According to Asheville’s Office of Sustainability, the city has cut its carbon emissions by 17 percent since 2007.

But Democrat Keith Young, who’s challenging Newman in the District 1 primary, says his opponent has spent too much time on environmental issues at the expense of pressing social concerns such as affordable housing. Young, a teacher’s assistant at Asheville City Preschool, says that while he would have voted for the carbon reduction goals, meeting them is “not my focus.”

The educator, who hopes to become the first African-American to serve on the Board of Commissioners, says, “You have people I want to represent that are left out.”

District 1 consists chiefly of the city of Asheville, where 47 percent of renters and 38 percent of homeowners are “cost-burdened” (meaning they spend at least 30 percent of their income on housing), according to a recent report by professor Mai Thi Nguyen of UNC Chapel Hill.

To address that, “The focus needs to be on homeownership” rather than renting, says Young, who also wants to change regulations to empower individuals and reduce the influence of developers. Young said he was preparing a detailed proposal but declined to give specifics.

Slim margin

Asked about her environmental bona fides, Board of Commissioners Vice Chair Ellen Frost points to green cleaning guidelines she drafted recently, as well her support for new energy-efficient school buildings and the carbon reduction goals.

“We know there’s a connection between asthma and using toxic cleaners,” she explains. “So at least we set an example that in county buildings we don’t use toxic cleaners.” Approved Feb. 18, the new guidelines instruct county departments to use “less hazardous products that have positive environmental attributes (biodegradability, low toxicity, low VOC content, reduced packaging, low life-cycle energy use).”

In addition, Frost helped win approval for the $20 million LEED-certified Isaac Dickson Elementary (now under construction) and a planned $40.5 million Asheville Middle School that will also include green building features.

The Democrat is completing her first term representing District 2, which includes Swannanoa, Black Mountain, Fairview and Weaverville. If re-elected, Frost says a top environmental priority will be finding ways to increase recycling, including establishing a drop-off point in east Buncombe.

But after unseating incumbent Carol Peterson in 2012 by only 38 votes, Frost faces a tough rematch in this year’s primary. And Peterson, who previously served eight years on the board, is emphasizing fiscal conservatism rather than any specific new environmental initiatives.

The retired educator, who owns a farm in Fairview, cites the county’s successful farmland preservation efforts as an environmental policy she supported (see “Thinking Big” elsewhere in this issue). Frost has also supported those efforts.

Carl Silverstein of the Southern Appalachian Highlands Conservancy, who helps arrange conservation easements, notes that Buncombe is one of only a handful of counties in the state to fund such deals. And since North Carolina legislators recently eliminated an applicable tax credit, county funding will be even more important as development pressures increase in the mountains, he says.

Chicken or egg?

District 3, the most conservative part of the county, includes Enka-Candler and Sandy Mush. In the Republican primary, Commissioner David King faces a challenge by political newcomer Miranda DeBruhl, a nurse and small-business owner.

In 2013, King was the only Republican who voted for the carbon reduction plan, though he took pains to distance himself from language in it that proved to be a major sticking point for his GOP colleagues: “The American Association for the Advancement of Science has determined, ‘The scientific evidence is clear: Global climate change caused by human activities is occurring now, and it is a growing threat to society.’”

“It’s not my job to pass judgment on whether there’s a worldwide problem,” King said at the time, calling the measure “a compromise” and “a local tax-saving measure.” DeBruhl, however, says she would have voted against the initiative. “The [environmental audit] alone is far too expensive, not to mention the overall cost has not been discussed,” she points out.

King, who serves on the Asheville Area Riverfront Redevelopment Commission, says he wants to see more greenways and multimodal infrastructure in the River Arts District. “All of that I see as an economic structure that helps broaden our tax base, which potentially helps lower the tax rate,” he explains, though he emphasizes that “We’re not going to go out and borrow $50 million and build greenways. Like any other infrastructure, it comes in time.”

DeBruhl, however, says, “When I hear ‘sustainability,’ I think about working to sustain our jobs and the economy. I’d rather see the money either returned to the taxpayers or invested in our schools.”

King, a member of the Economic Development Coalition for Asheville-Buncombe County, says, “It’s like a pyramid we’re trying to build: Without jobs, we can’t grow our economy to sustain our schools and provide infrastructure they need. And if we don’t have the quality of life, we can’t attract the jobs. So it’s like a chicken or the egg thing: We’ve got to have all of this.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.