A normally quiet corner of Asheville’s Kenilworth neighborhood has been humming in recent weeks as volunteers wield weed whackers and hammers. Their work is part of the latest effort to rescue Western North Carolina’s oldest known African-American cemetery from the ravages of neglect and obscurity.

Between at least the mid-1800s and 1943, nearly 2,000 human bodies were crammed into the 2-acre patch of land at the end of Dalton Street, adjacent to the St. John “A” Baptist Church. Most of the graves are unmarked; many contain the last remains of slaves and other black citizens whose lives and contributions to the community have been largely unrecognized.

In the decades since its final burial, the cemetery fell victim to the relentless spread of poison ivy, kudzu and briars. George Gibson, who helped bury bodies there as a boy, says that when he revisited the site in 1986, he was disturbed to see it “in a shamble” and vowed “to get it back to how I had seen it: A clean cemetery.”

- Photo by Jake Frankel

- Photo by Jake Frankel

- A small unkept trail leads into the cemetery. Photo by Jake Frankel

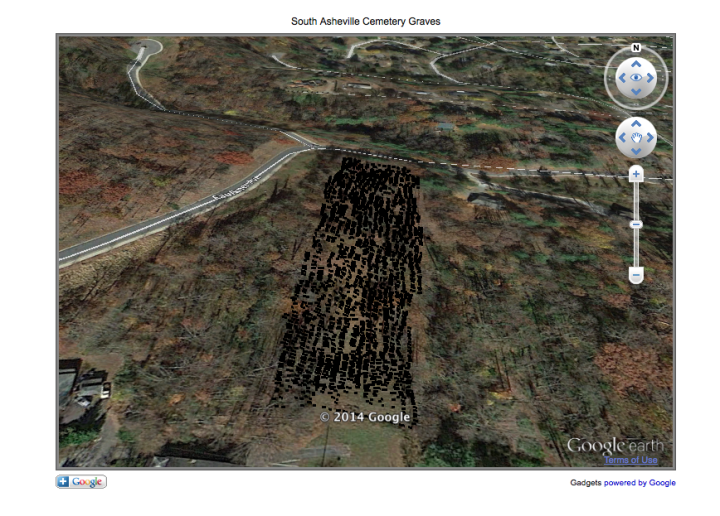

- All but 93 of the cemetery’s 1,963 graves lack tombstones. Photo by Hayley Benton

- George Avery was a former slave who, upon gaining his freedom, served as the cemetery’s primary caretaker until his death in 1940. Photo by Jake Frankel

- Photo by Hayley Benton

It began as a one-man mission: “I came out there with just a hedge clipper, a pair of loppers,” he recalls. Gibson was soon joined by his friend George Taylor, who also grew up nearby. But the property was too far gone by then for two pairs of hands to be able to save it, and though groups of volunteers have since intermittently gotten involved, the results have been mixed. Several times they’ve beaten back the weeds, only to see them reclaim the site soon after (see “If Stones Could Talk,” Sept. 23, 1998, Xpress).

Now 86 and blind, Gibson can no longer help with the hard physical labor of clearing brush, but he’s hopeful that the revived efforts of the all-volunteer South Asheville Cemetery Association will achieve what he’s always dreamed of.

As a child, Gibson worked alongside George Avery, a former slave who, upon gaining his freedom, served as the cemetery’s primary caretaker until his death in 1940 at age 96. And in a development the two of them couldn’t have imagined back when they were burying those dead, a class of Warren Wilson College students recently completed a website that features an interactive map of the cemetery and a digital guide to each of its graves. (To date, 1,963 have been identified — two of them since the map was completed — and it’s possible that a few more might turn up.)

A living memory

The idea behind the website (southashevillecemetery.net) is to “nurture a living memory of African-American history in this region and promote awareness about it,” says global studies professor Jeff Keith, who led the project. “It’s a place of great spiritual and historical value. My goal is to celebrate that. … I’m hoping the website can make it a place that people can access, even if they don’t come to Dalton Street. My hope is that this will result in it being maintained forever.”

Keith’s student team built on the work done by archaeology professor David Moore and his students. Throughout the late ’90s and early 2000s, they probed the ground to discover and catalog the graves, all but 93 of which lacked tombstones. Because the bodies were often buried in pine coffins and wicker baskets, however, they decomposed quickly, leaving measurable cavities in the earth.

The archaeology team pinpointed where the bodies had been placed. But their blueprint remained largely inaccessible to the public until the new website harnessed GIS and Google Earth technology to readily display the map to anyone with computer access. Users can now explore the cemetery digitally, zooming in on each grave and clicking it to see what information archaeologists were able to unearth.

That data, however, is limited: The digital record indicates whether there’s a carved tombstone, a simple unmarked fieldstone or any other noticeable marking. Any information on the headstones is recorded. Some give names as well as birth and death dates; others bear only simple carved hints, such as “mother” or “our darling.” It isn’t known how many of the deceased were slaves.

“I find it fantastic to use the tools of the 21st century to tell stories of the 19th century. It’s also a huge challenge,” says Keith. “This is a unique effort in Western North Carolina. I don’t know of another African-American cemetery that’s being investigated this way.”

Segregated imaginations

Although much of that history has been “lost to time,” notes Keith, “The cemetery offers some clues to what African-Americans have done for Buncombe County.”

A dozen or so stones, for example, are marked with masonic symbols suggesting, he says, “that there were builders there who probably contributed to some of the iconic buildings of downtown Asheville.” And the sheer scale of the burial ground, continues Keith, also goes a long way toward countering the claim that slavery barely existed here. Because WNC lacked the large-scale plantations that popular culture often associates with the institution of bondage, he says, he often encounters people who believe there was no slavery in the mountains.

“I think Appalachia, as a place, is often racialized to be white by media representations. … Sometimes people move here and they don’t have a clear awareness of the tremendous contributions that African-Americans made to this place,” says Keith. “We have segregated imaginations: We think about the past in ways that are limited by our assumptions. But when you really engage with the past, you find all kinds of exciting stories that defy those assumptions.” The cemetery, he adds, “prompts people to ask questions about the past that they might not otherwise consider.”

The new website was inspired by a partnership between Buncombe County and The Center for Diversity Education at UNC Asheville last year, which resulted in the digitization of local slave deeds (see “Bought & Sold: Forgotten Documents Highlight Local Slave History,” April 9, 2013, Xpress). The records attested to the thousands of slaves who toiled in Buncombe County as masons, cooks, farmers, tour guides, maids, blacksmiths, tailors, miners, farmers, road builders and more. They also underscored the fact that many of the prominent names assigned to city streets and buildings are those of some of the area’s biggest slaveholders.

The land encompassing the South Asheville Cemetery once belonged to William McDowell, who also owned Avery and an untold number of other slaves buried there. The Confederate major’s name now graces one of Asheville’s main thoroughfares, and his former mansion, built by slave labor, is now a history museum.

“In Asheville everything’s named after white people, and we don’t have an awareness of the important contributions of slaves. This is what motivated [Register of Deeds] Drew [Reisinger], and it also motivates me,” says Keith. “I hope that the tools of the digital humanities and, in general, use of the Internet will allow us to create greater awareness about the complexities of the past and the many different types of people who’ve contributed to the American story.”

Building community from segregated roots

When David Quinn, president of the South Asheville Cemetery Association, greeted a group of seven AmeriCorps volunteers who came to town last month to help renovate the site, one of the first things he did was take them on a tour of Riverside Cemetery.

Overlooking the French Broad River, the 87 acres of rolling hills in Montford are immaculately maintained by the city of Asheville, the green lawns punctuated by intricately carved headstones and majestic oaks. An air of respect, honor and history reigns at Riverside, the final resting place of many prominent area residents, including author Thomas Wolfe and Gov. Zebulon Vance.

“That’s what we need to eventually get to,” Quinn told the volunteers before they began constructing a wooden fence around the South Asheville Cemetery’s perimeter. “That’s the kind of look and respect we’re going for.”

Owned by the city, Riverside Cemetery also has a cutting-edge website featuring comprehensive records of its inhabitants, photos and interactive GIS maps. Although the facility did start accepting the bodies of African-Americans in 1885, they were limited to a segregated section until 1952. But as Gibson remembers it, the South Asheville Cemetery presented the only affordable burial option most local blacks had for more than 100 years. When he worked there, plots went for $7, $5 of which went to the McDowell family; the other $2 was divided among the gravediggers, he says.

In contrast with Riverside’s well-marked grounds, diggers in South Asheville often had to rely on Avery’s memory to know where previous burials had taken place, sometimes accidentally encountering remains as they dug new holes, Gibson recalls. The Kenilworth site is roughly six times as densely packed with bodies as Riverside. And that fact, says Keith, demonstrates “something about the perceived value of people: We segregated people in the afterlife. It shows how ingrained segregation had become. It invites us to think about inequality.”

The new fence surrounding the South Asheville Cemetery (which the association now owns) and the native grass to be planted there (perhaps this fall) are being funded by $13,000 in donations raised recently from various sources, says Quinn, who’s been working at the site for 16 years. He believes the current efforts will succeed where others failed, because there’s more community interest now than he’s ever seen, with volunteers coming from a wide range of schools and churches. The website project was even featured on National Public Radio.

And though its origins are rooted in segregation, “The cemetery is becoming a vehicle to bring the community together. It’s a community builder,” says Quinn. Still, for the group to maintain the necessary momentum, they’ll need to continue to grow that community of support. Assistance from the city, the National Register of Historic Places and any other organizations or individuals would be very appreciated, says Keith, who’s also an association member.

- AmeriCorps volunteers. Photo by Hayley Benton

- AmeriCorps volunteers. Photo by Hayley Benton

- Caretakers at St. John “A” Baptist. Photo by Hayley Benton

- David Quinn, president of the Cemetery Association. Photo by Hayley Benton

“It’s almost like these are forgotten people, and it’s important that they have a place that’s taken care of, a resting place that’s right,” says Gibson’s daughter, Olivia Metz, who’s also an association member.

Her father, meanwhile, sees the progress as nothing less than a dream come true.

“God is blessing us with volunteers, help. … It was my dream that somebody would come,” says Gibson. “I was taught that God would make a way, and that’s what he’s showing me now: that what I desired to do, to see, is now coming to pass.”

Burying the Dead: Memorial for Slave Cemetery, Asheville, N.C.

(A poem by Glenis Redmond)

In our town

out of sight

past Wyoming Street

up on the hill behind St. John’s Baptist Church

lay aged bricks, rocks and baskets of bones,

where the dead are not truly dead,

their silent mouths far from quiet.

Speaking crow they wrestle the blueness from night

and lift sorrow from its deeply veiled sleep.

Through Kenilworth

runs an Indian trail,

a forested hill

I could call my own.

I don’t.

Not too far from downtown

living beneath the tangled brush

a cemetery of slaves merge with the Cherokee and their trail

unmarked lines carrying both streams of blood

that course unceasingly through my veins.

Both trails have found my heart

intersecting where spirit meets bone

and I have taken to walking the block

putting down feet and prayer

on both foreign and familiar ground.

On this walk I am found,

joined, graced and haunted

by an urgent need quite like death and birth.

Call it a bitter dream I keep reliving

try to pin it on the past

remind myself of the passage,

the dead will bury their own

they haven’t so the crow flies,

pecks and caws on my forgetfulness

calls to me through shutters tilted open.

I rise from my couch of restless sleep.

I rise from my doing

from the mundane task of washing clothes.

I rise because I cannot wash my hands of this

these spirit bodies hovering

souls littered across the land

calling to open skies,

open hearts,

any vessel open

as to how they have not rested in life or death;

how they have not claimed this land

or purchased a stone to mark

their passing.

Lost

on a hill

behind a church

in a town

in these mountains.

This cry is not made of “i”

it is made of a glorious tormented collective

of a blueblack and red “we.”

Spirits torn

into a cry so bitterly ruined

of broken wings, cracked bones and splintered dreams.

Screaming the woes of heavy air

and the pain it takes to turn gospel into blues;

a weight only crows can carry

on their blueblack backs

singing the harsh call to be heard

the call of crows

chanting through unpleasant beaks

the unsingable to us,

we who are on earth walking

are indeed

the dead

in need

of waking.

Wonderful story about the South Asheville Cemetery. Since starting a search for my own ancestors it has been heartbreaking to find cemeteries over taken and uncared for. Many are on private property so you don’t know if you are allowed to visit or do any cleaning of the graves. So happy to see people coming together to honor those who have gone before us.

What a great story! This embodies the best ideals that the founders of Warren Wilson College envisioned as a community of students and scholars contributing to the Community they are in the midst of.

This is genuine work study into the history and future of our African American community in Western North Carolina. Good story Mountain Express!