When local businessman Dick Gilbert and folk singer Andy Cohen opened their coffeehouse, Asheville Junction, in 1975, they were looking for talented local musicians to perform for the growing folk music scene. Their search led to Walter Phelps, a then-elderly African-American artist who had been a local celebrity in the 1930s. Phelps and his wife, Ethel, were living in poverty in Asheville’s Valley Street neighborhood.

“I had gone down to the corner behind the County Building and asked around about ‘that old guy who used to play blues around here’ and was directed to May’s Place, where you went to play the numbers,” says Cohen. “[Walter and Ethel] were there having a beer. We talked for a bit, and I asked them to come to the Junction, which was up the hill from there.”

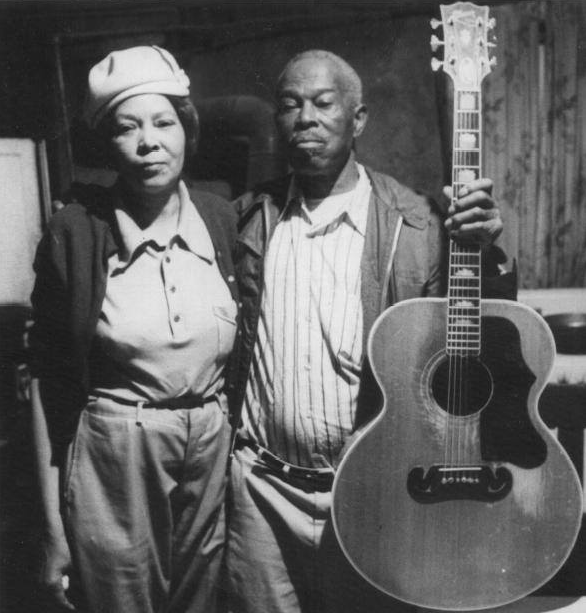

The Phelps duo, it turns out, was a surprise hit. Ethel sang, while Walter played guitar. “There were about 25 or 30 people the night they first played, and we made some money,” Cohen remembers. “I like to think their existence was a bit of a revelation to the people who frequented the place.”

He continues, “Old-time fiddle music is a major export from Asheville, [that although] the town is completely surrounded by blues players in every direction, what few of them lived here didn’t have much of a chance against the fiddles and banjos.”

Walter and Ethel’s blend of gospel, Delta blues and 1920s ragtime captured the imagination of the Asheville folk scene. They became regular performers at the Junction.

Local musician Dan Lewis, who was there that first night in 1975, says he felt an instant connection with the Phelpses’ music and charismatic personalities.

“They were the kind of people who you gravitated to and wanted to hang out with,” says Lewis. “There was something about their music that was spontaneous and energetic — I had to play music with these people. I was a long-haired white kid, and they were old enough to be my grandparents, but we quickly became close friends.” The three began performing together, with Lewis on the bottleneck slide guitar while Walter played rhythm guitar and Ethel sang. Lewis booked them gigs at local coffeehouses and bars, including the Town Pump and McDibb’s in Black Mountain. In 1978, they were the featured performers at the John Henry Festival in Princeton, W.Va., and, in 1980, they performed at Bele Chere.

Lewis played and recorded music with Water and Ethel for 10 years, until Walter’s death in 1985. Ethel died the following year.

According to Edward Kamara’s Encyclopedia of the Blues, Phelps was born in 1896 in Laurens, S.C., and was both a contemporary and acquaintance of bluesmen Pink Anderson and the Rev. Gary Davis. In the 1920s, Phelps first came to Asheville in the employ of Dr. Nonzetta and Chief Thundercloud, a pair of snake oil salesmen who ran a traveling medicine show.

“This was back in the days before the Food and Drug Administration, so [for] these snake oil medicine shows, people would cook up batches of tonic that had sugar and coloring, molasses, white liquor — God knows what else in there — and sell it as medicine,” says Lewis. Nonzetta and Thundercloud would pull up to Pack Square on the back of a flatbed truck. On a makeshift stage, Phelps would, as he phrased it to Lewis, “play music, cut shines and tell lies.” After the performance, Nonzetta and Thundercloud would sell their tonics, and Phelps would wander through the audience peddling moonshine.

Phelps decided to settle in Asheville, and, despite having to contend with systemic racism of the times, he thrived as a performing artist.

“Those times were very segregated,” says Lewis. “And yet Walter, because he was a musician, was able to cross a lot of interesting barriers and be places where there were normally few black faces at all. For example, the old Sky Club … a high-class speakeasy. Rich people would come there for gambling, entertainment and illegal liquor. Despite the ‘whites only’ policy, Walter and his friends would periodically play music there.”

In 1940, Walter and a friend were hired by the segregated Imperial Theater on Patton Avenue to sit on a hay bale and play music to draw crowds to the movie Gone With the Wind. According to Cohen, Walter also claimed to have been a part of a jug band that performed at McCormick Field, playing on the top of the dugout during the seventh-inning stretch. The band consisted of several guitars and a banjo, and an instrument that Phelps called a Kazooxaphone, which was made by attaching a length of garden hose to a kazoo on one end and a funnel in the other. “In exchange for the musical entertainment, Walter said he and his band were allowed to watch the games for free,” says Cohen.

As time passed and musical styles changed, interest faded in the blues that Phelps played. In the 1940s, too old to fight in World War II and no longer making money as a musician, he took a job working on the construction of the Fontana Dam in Swain County. He worked there for several months until a minor injury convinced him that the job was too dangerous. He returned to Valley Street, where he and Ethel were married. Ethel was 20 years Walter’s junior and a gospel singer in a local church choir. The couple lived in relative obscurity on Valley Street until meeting Cohen in the ’70s.

Lewis lives in Weaverville and still performs locally. He continues to play the songs that he learned from Walter and Ethel, and has many recordings of their performances together, including a studio album that has yet to be released. He plans to host a crowdfunding campaign through Kickstarter to raise the funds so that he can continue to share the music of Walter and Ethel Phelps in the 21st century.

“In a way, it’s about culture,” says Lewis. “It’s when people finally get the chance to experience, to be exposed to [another] culture they realize that there are wonderful things we have to share with each other. And until you do, you don’t know.”

Walter and Ethel exposed a lot of people to music that they never would have heard otherwise. “It was like a time machine when you were listening to them,” says Lewis. “You were back in their era.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.