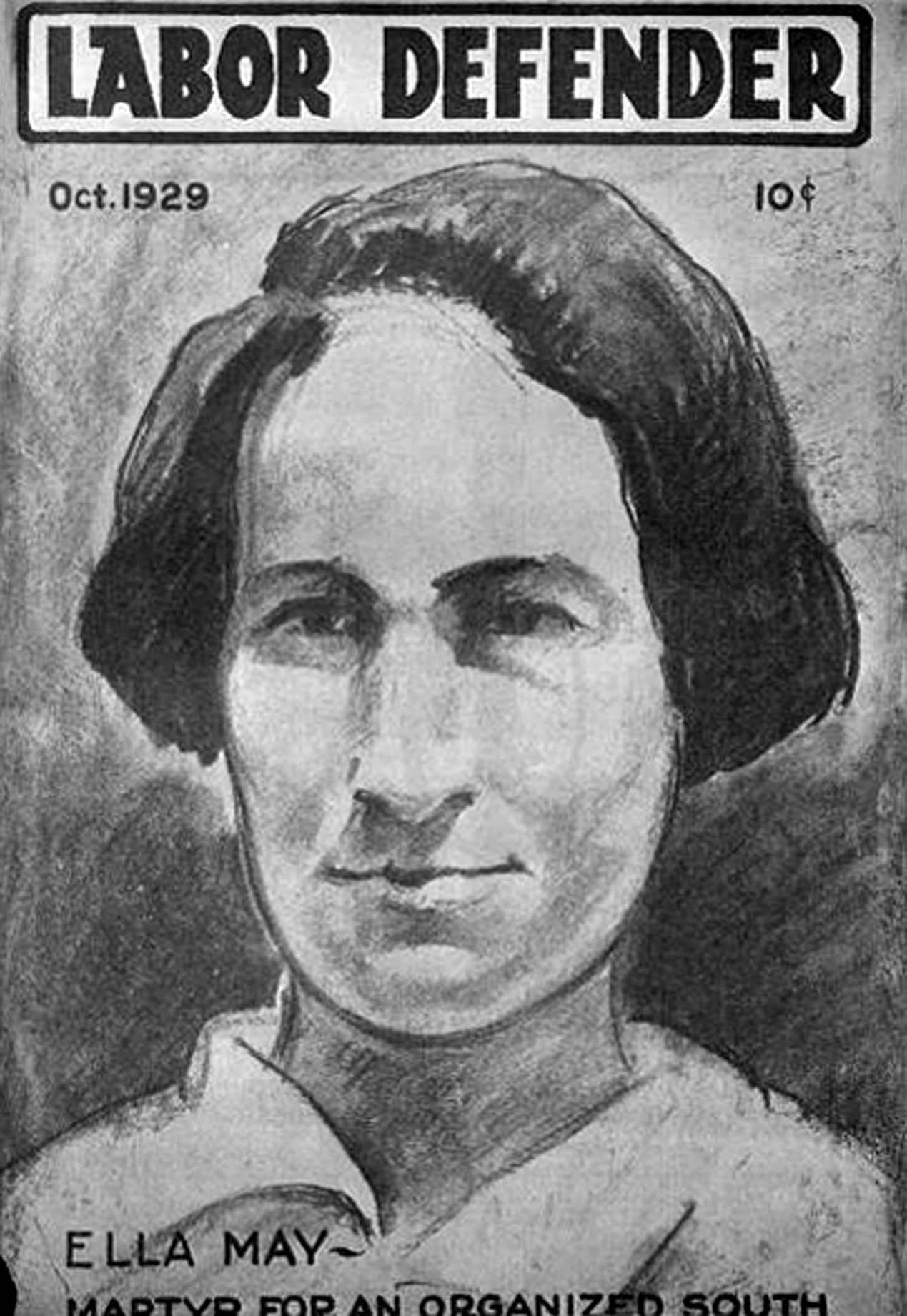

In the spring of 1929, workers at the Loray Mill in Gastonia, the largest textile mill in the world at that time, took to the picket lines to demand better wages and working conditions. Among the strike leaders was Ella May Wiggins, a southern Appalachian native, “mill mother” and balladeer, who defied social norms by organizing black mill workers at the height of Jim Crow.

Her tireless energy, iconic ballads and tragic assassination in broad daylight while driving to a Union meeting in 1929 made international headlines and inspired folk legends like Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie to carry on the fight for worker equality.

In July 2015, local author and teacher Kristina Horton — Wiggins’ great-granddaughter — published Martyr of Loray Mill, a biography of her forebear, with McFarland Publishing.

Xpress spoke with Horton ahead of her reading at Malaprop’s on Sunday, Jan. 17, to discuss Wiggins’ life, the meaning of her struggles and why it remains important to remember Ella May’s sacrifice.

Xpress: How did you first become interested in the story of your great-grandmother?

Horton: Oddly enough, I don’t remember any childhood stories about Ella May. My grandmother Millie passed away when I was 10, so I lost an opportunity there to find out things from her.

I didn’t really start digging until I went to college. My freshman year, we had a writing course where we were asked to write about an ancestor who inspires us. I became more curious in her; as a senior, I wrote a 30-page paper on Ella May.

At that point, I realized there was a really big story here, something that not only I would be interested in, but others would be too.

Was Ella May discussed much within your family growing up?

My grandmother never talked about Ella May much, nor did her sisters and brothers. Ella May was hated by the majority of the community in 1929, and her children lived in fear — I mean, their mother was murdered! They were scared to death.

The last year of Ella May’s life was an extremely violent time. The spring [the family] received their water from was poisoned; Myrtle, Ella May’s eldest child, was raped when she was 11 in front of her sisters and brothers.

After their mother died, the children held onto that fear. They were afraid that by association, their children could be attacked. Even today, when Ella May is seen as a hero, there’s still a discomfort I see in my mother’s generation.

There’s no shame there — it’s just the unknown and the fear their parents had when they talked about her.

What was Ella May’s childhood like? How did growing up in the mountains influence her later work?

She grew up in Sevierville, Tenn., where Dollywood is currently located. In her early years, she lived on a subsistence farm like most mountain families. They lived a very meager existence, but there was pride in being in charge of yourselves, deciding what work you do and how you do it.

From all accounts, she had a happy childhood. She was a bit mischievous: She apparently loved to jump into the water every chance she got, which drove her parents crazy. I was a swimmer in college, so little things like that I really connect to. She’s not just this larger-than-life figure: She’s a mother, grandmother, a human being.

At the age of 13, her family moved around with the logging industry. That’s really where her music started to shine. Anyone that writes about Ella May talks about how she had the type of personality people are drawn to.

I really believe that Ella May being brought up in the mountains influenced the person she was. Mountain culture instills pride, independence and self-determination. Those that live in the mountains are accustomed to being in charge of their lives.

How did she become involved in the textile industry and subsequently the labor movement among Southern mill workers?

Her husband was injured in a logging accident and suddenly found it hard to find employment. At the same time, the logging industry was dwindling, so they decided to move to the Piedmont. The textile industry was one of the few places where women could work at that point in history.

Like many workers, she had high hopes, but found that she really couldn’t make a livable wage. When 1928 came along, she was working for $9 a week. At that point in time, four of her nine children had died. She couldn’t feed them properly or provide proper medical care. Oftentimes, if she stayed home to care for a sick child, she would be fired.

Ella May also had a reputation for speaking her mind, which didn’t go over well with her employers.

When Communist labor organizers came south to the Loray Mill, Ella May joined right away. She was a secretary for the Union. As the strike progressed, she took a more vocal role.

Ella May’s music resonated much more than [the Northern organizers’] speeches did. She didn’t have an especially pretty voice, but her presence moved people deeply. Nothing moves workers more than hearing one of their own speak about their experiences.

Why do you think Ella May was able and willing to organize black mill workers during such a racially charged time?

There were no airs about her. Most whites living in the Piedmont at the time thought of themselves as superior to black workers. But Ella May didn’t grow up in a place were there was much prejudice or even classes. She carried that heritage with her. She saw black workers as her equals.

When she’d go to Union meetings, there’d be a rope dividing whites and blacks. She was the only white person who would go across to the other side. And honestly, she was as poor as them. She lived in a black mill community. She suffered alongside of them. She knew what they were going through, because she was going through it too.

How has writing this book impacted your understanding of her death?

When I started researching this, I wanted to find out who killed Ella May. I was very angry about how she and all these textile workers were treated — the beatings, the rapes — just for trying to make a better life for their families. It was just atrocious.

But as I dove deeper, I realized that at that time, not only the mill owners but entire communities were afraid. The textile industry was the Piedmont’s bread and butter, so to see these Northerners coming down — they felt like their lives were under attack. Of course, fear does not justify violence, but I have a better understanding of why it happened.

Besides the book tour, what other projects are you working on?

I’m part of the Ella May Wiggins Memorial Committee. We’re a nonprofit organization dedicated to getting a life-size statue of Ella May. Just recently we reached the $10,000 mark; we expect it to cost $80,000 in total.

Also, there’s a Mill Mother’s Lament album that North Carolina musicians have put together of Ella May’s songs and ones of a similar nature. I’m selling the CD on my book tour, as well as on our website, ellamaywiggins.org. All the proceeds goes to funding the Ella May statue.

I also really want to work on trying to get a movie made. In the 1980s, my family had an agreement for a movie, but it didn’t end up going through. That was before there was a book, so I’m pretty confident that I’ll be able to get some traction with that. I’m also thinking about writing a children’s book on her, geared to the fourth grade level.

Why is it important to remember Ella May’s legacy today? What can we learn from her story?

I think there’s a great importance for us to understand our ancestors’ struggles, because they went through them for us. There are many lessons to be learned. They made so many sacrifices for the future generations, and it’s our duty to remember them and what they went through. Even more than that, we need to pay it back by giving to the next generation.

I actually used to work at a Union door factory as management. I felt like my job was to drive people to work harder and harder. I wasn’t making their lives better necessarily, whereas, as a teacher, I can have an impact, especially on young children.

I think Ella May’s story isn’t just important for me, it’s important to North Carolina and this nation’s history. I really see her as a champion for the working class. I think we need to have more heroes like that.

Kristina Horton will hold a reading and presentation on Martyr of Loray Mill on Sunday, Jan. 17, beginning 3 p.m., at Malaprop’s Book Store & Cafe, 55 Haywood St., downtown Asheville. To learn more about the Ella May Memorial Committee, donate to the Ella May Statue Fund, or purchase the Mill Mother’s Lament CD, visit ellamaywiggins.org or check them out on Facebook.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.