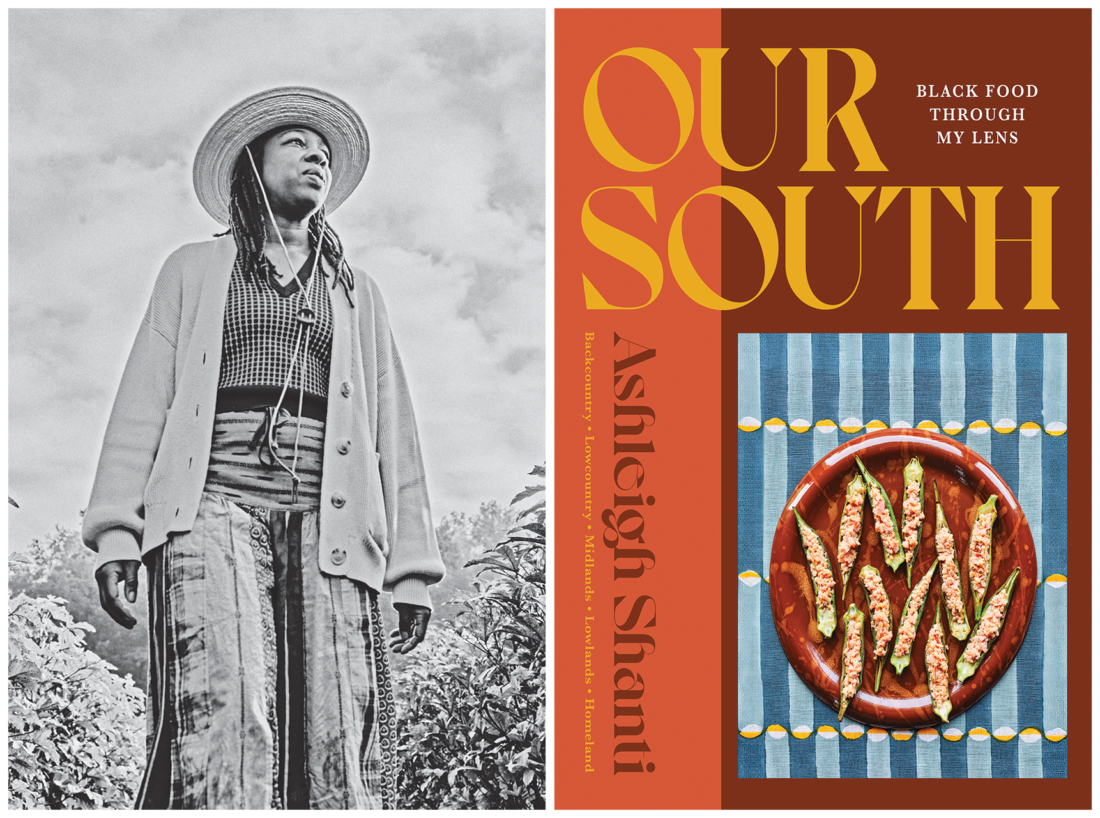

Preceding chef Ashleigh Shanti’s warm, conversational and engaging introduction to her first cookbook, Our South: Black Food Through My Lens, is a short author’s note telling the reader what the book is not.

It is not, she writes, an Appalachian cookbook, a book filled with her family’s soul food recipes, a Southern cookbook or a chef book. As the subtitle says, it is Black food through her lens.

“People probably have expectations when they read the title Our South,” she says, having just finished cooking “snacks” for an event at King BBQ in Charleston, S.C., celebrating the book’s publication. (Only a chef would casually use the term “snacks” for white shrimp in lettuce wraps with mango and plantains, and smoky ham barbecue oysters on the half shell.)

“It’s always gotten under my skin how people identify Southern food as this one thing,” she continues. “As a Black chef, I am influenced by the African diaspora, all the microregions of the South and how incredibly diverse our foodways are. That is how I cook, how my family cooks and how many Black chefs cook.”

Thinking of cookbooks she admires, she realized they all have a genuine sense of place. So she decided it was important for her to write a book that highlights the places meaningful to her and how they shaped her as a chef. “To write the proposal, I essentially moved back to my childhood bedroom in my parent’s house where I grew up and the kitchen where I baked my first cornbread,” she says.

At the time, in the wake of COVID-19, she had recently left Benne on Eagle — where she had received a finalist nod for the James Beard Foundation’s Rising Star Chef of 2020 — and felt that it was a good time to get quiet and write. It was then that she determined the book would flow by the regions, cultures and people that had profoundly impacted her life.

Through recipes, stories and color-drenched photos by Johnny Autry of food, people and places, Shanti’s book travels across the South through sections labeled “Backcountry,” “Lowcountry,” “Midlands,” “Lowlands” and “Homeland.”

“I was doing the regions that shaped me as a chef, and they were easy for me to travel to and see family,” she explains. “I really enjoyed that time, the memories and nostalgia, seeing aunties and uncles I hadn’t seen in years. They told stories and shared traditions and recipes. It was so special.”

That sense of attachment and affection is fully expressed in the introduction to each region. In “Backcountry” — or the Appalachian South, as she knows it — she recalls her great-aunt Hattie Mae and how she taught young Ashleigh the names of the edible things she foraged from the woods. This chapter offers recipes for chow chow, kilt lettuce, apple butter, soup beans, hot-water cornbread and stewed rabbit.

“Lowcountry” refers to the Coastal South; Shanti was unexpectedly born in St. Mary’s, Ga., when her parents were there for a family wedding. They often returned to visit her father’s family there and in Edisto Island, S.C. The smoky ham barbecue oyster and white shrimp in lettuce wraps recipes are in this section.

In “Midlands,” Shanti introduces readers to her great-grandmother Inez Miller of Mayesville, S.C., an area the chef remembers for its bounty of produce. Here dishes celebrate fresh-picked goodness on the table and the time-tested practices of pickling, preserving and putting up fruits and vegetables.

“Lowlands” — specifically Tidewater, Va. — is where Shanti grew up and where she began working in restaurants as a teen. Recipes here, like the savory cabbage and mushroom pancake and the chipped Virginia ham breakfast toast, evoke her mother’s kitchen.

“Homeland,” Shanti says, is where she is now. “Homeland is Asheville; it’s me cooking as a Black, queer, woman chef.”

It is where she opened her first restaurant, Good Hot Fish, in January, a tribute “to the fish-frying women in my family, who would hold up brown paper sacks of cornmeal-dredged fresh, fried fish and shout out, ‘Get your good hot fish here!’” It’s where she and her wife, Meaghan Shanti, bought their first home this summer.

It’s where the tour for Our South was set to kick off on Oct. 15. That plan was scuttled in the wake of Tropical Storm Helene and instead, like so many in Asheville’s restaurant industry, Ashleigh Shanti found a new way to feed her community. “We started doing Sweet Relief pop-ups with what we all [including Neng Jr’s chef/owner Silver Iocovozzi] could salvage from our restaurants and donated product,” she says. “We went into underserved communities, set up cafeteria-style and filled people’s plates with hot food.”

Plans for reopening Good Hot Fish are a work in progress as Asheville still struggles to access potable water. Meanwhile, the chef has taken some of her team on the road to cook for the book’s release tour, which began in Richmond, Va., on Oct. 20 and has wound its way through Charleston and Savannah, Ga., and will stop in New Orleans at Turkey & the Wolf restaurant on Tuesday, Nov. 19.

“I’ve been able to cook for family members who come to the book events — many of them are featured in the book,” Shanti says. “They know the importance of preserving these recipes and traditions and are just incredibly proud.”

Our South: Black Food Through My Lens is available locally at Malaprop’s Bookstore/Café, 55 Haywood St. and avl.mx/e8r. For updates on the reopening of Good Hot Fish, follow the restaurant on Instagram at avl.mx/e8p.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.