By Greg Barnes, North Carolina Health News

Alexis Barbarin isn’t sure why North Carolina is reporting fewer cases of tick-borne diseases this year.

Normally, by this time, hundreds of cases would have been reported, said Barbarin, the state’s public health entomologist, whose job it is to track diseases transmitted by insects. Instead, she said, only 76 confirmed and probable cases of Lyme disease and 74 cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever have been reported.

One would think, in this time of the coronavirus pandemic, that people would be communing more with nature — hiking, having picnics, exploring the great outdoors — in places where ticks love to live.

Figures from the state Division of Parks and Recreation show that to be the case.

The pandemic forced the closure of all but 12 state parks for several weeks in the second quarter of 2020. But visitors to parks shattered last year’s attendance numbers over the Memorial Day and the Fourth of July holidays, and people have flocked to the parks that remained open, the figures show.

“The dramatic increase in visitation in some of our parks have shown us the critical importance of state parks to our citizens, particularly during this difficult time,” division spokeswoman Katie Hall said in an email. “People are seeking outdoor experiences for both relaxation and active recreation as a way to process the big changes and stressors our citizens have faced in their lives due to COVID-19.”

Cases going unreported

So why haven’t there been more reported cases of tick-borne illnesses?

Barbarin said one likely reason is that health care professionals have been so slammed with coronavirus patients that they haven’t had time to regularly log cases of tick-borne infections. Another reason, at least for Rocky Mountain spotted fever, is that the case definition changed in January, increasing the threshold for reporting positive cases, she said.

Another way to get an idea of tick activity is to look at the number of times people have gone to the website Tick-Borne Infections Council of NC, or TIC-NC. In the early months of the coronavirus pandemic, the website got little traffic. That changed in May, when Gov. Roy Cooper lifted his stay-at-home order and traffic spiked and continues to be elevated.

“There’s no way to prove this, but I think it’s pretty safe to assume that the hits increase because people are getting tick bites and have questions,” said Marcia Herman-Giddens, an adjunct University of North Carolina professor and the scientific adviser for TIC-NC.

Some things are certain, though: Ticks are spreading southward in the state, more tick-borne diseases are being discovered, and the problems aren’t going away.

Ticks on the move

In the spring of 2019, state health officials were notified that three children attending a wilderness day camp near Asheville had contracted Lyme disease, a bacterial infection transmitted by the bite of an Ixodes scapularis tick — often referred to as the deer tick or blacklegged tick — that is infected most commonly with the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi. A fourth child had been infected at the camp in 2017.

According to a report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it was the first time a cluster of Lyme disease patients with a common exposure had been found so far south. The report was co-written by Barbarin.

Since then, a resident in Cherokee County submitted a tick Barbarin believes is Ixodes scapularis to the NC Animal Tick Identification Program. Although awaiting national verification, Barbarin said that would be the farthest south and west the species of tick has been found in North Carolina. She said the tick has also been found in Mecklenburg County and many counties to the east.

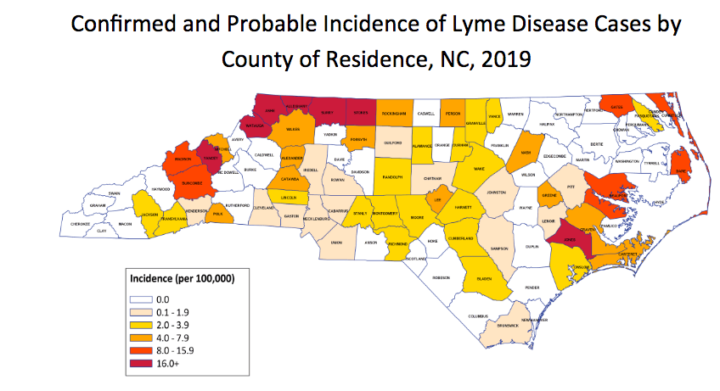

Lyme disease is not particularly prevalent in North Carolina — the incidence rate last year was 3.3 cases per 100,000 people, compared with the national average in 2018 of 7.2 cases per 100,000, according to the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services.

But North Carolina’s incidence rate for Lyme disease has increased over the past five years, led by Ashe, Alleghany, Surry, Stokes, Watauga and Yancey counties in the northwest.

‘A whole different world’

Herman-Giddens said she has been hiking in the woods in Ashe County for 40 years. She owns a cabin there.

In all of those years, she said, she had never been bitten by a tick until last year, when she pulled two blacklegged tick nymphs off her skin.

“It changed everything because it used to be a refuge going to the mountains,” she said. “You could just plow off into the woods and not worry about ticks, but now you do.

“It’s starting to be a whole different world, tick-wise, up in the mountains, sadly.”

Herman-Giddens didn’t contract Lyme disease, but she considers herself lucky. About 25% of the ticks in Ashe County carry the bacteria that causes the disease, she said. The nymphs are so small — about the size of a poppy seed — that most people don’t initially even recognize that they have been bitten, she said.

“Imagine trying to find a poppy seed stuck somewhere on your body, especially if it’s someplace you don’t see, you know, like the back of your neck or under your arm,” she said “That means if it’s on you 24 to 48 hours or more, it’s highly likely to have been transmitted so that means you’d have a one in four chance of getting it. It’s scary.”

The incidence of Lyme disease in Ashe County has skyrocketed since 2016, largely because of the migration of deer — the primary carrier of the blacklegged tick — from Virginia to the north, Herman-Giddens said.

Symptoms of Lyme disease

Lyme disease, like other tick-borne illnesses, can be debilitating. Early signs include fever, chills, headache, fatigue, muscle and joint aches, swollen lymph nodes and a rash resembling a bullseye at the point of the bite that can take up to 30 days to appear.

Untreated, Lyme disease can cause severe headaches and neck stiffness, arthritis with severe joint pain and swelling, particularly in the knees and other large joints, facial palsy, and heart conditions, according to DHHS.

The blacklegged tick is just one species in North Carolina that causes disease. Others include the Lone Star tick, the brown dog tick and the American dog tick. Rocky Mountain spotted fever is the most prevalent tick-borne disease in the state, occurring largely in the central and eastern portions of the state.

But there are other types of ticks, as well, and the state keeps discovering new species and new diseases.

Fierce Asian longhorned tick

North Carolina faces a new threat from the Asian longhorned tick, which was first reported in the United States in 2017.

Last year, the state confirmed that a Surry County farmer lost five cows to the Asian longhorned tick from acute anemia. According to the Southern Farm Network, a young deceased bull was brought into the state’s Northwestern Animal Disease Diagnostic lab with more than 1,000 ticks on it. The owner had lost four other cows under the same circumstances.

Basically, they had all bled to death.

At that time, the Asian longhorned tick had been confirmed in four North Carolina counties; Surrey, Polk, Rutherford and Davidson. Barbarin said the tick has now been found in 10 of the state’s counties. The others are Madison, Alexander, Haywood, Wilkes, Rowan and Macon.

The CDC reports that although no people have fallen ill from an Asian tick bite in the United States — it “appears to be less attracted to human skin” — disease has been spread to humans in other countries. Barbarin said an Asian tick was removed from a person in Davidson County.

“With ongoing testing of (Asian) ticks collected in the United States, it is likely that some ticks will be found to contain germs that can be harmful to people. However, we do not yet know if and how often these ticks are able to pass these germs along to people and make them ill,” the CDC reported.

The CDC says a recent study found that Asian ticks are unlikely to carry the bacteria that causes Lyme disease, but another study found that they can carry the bacteria that causes Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Barbarin said the state Department of Health and Human Services is working with a researcher at N.C. State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine. Whenever an Asian longhorn tick is found, it is sent to the researcher to test for pathogens, Barbarin said.

“So far, she hasn’t found any pathogens in any of the tests that we’ve submitted,” Barbarin said. “But the numbers of ticks that we’re getting, again, is fairly low, so we would need a more robust sample to determine if these ticks are actually infected.”

Other tick-borne diseases

While the Asian longhorned tick becomes a growing concern, researchers are watching out for other tick-borne diseases in the state, including those caused by the Bourbon and Heartland viruses.

The Bourbon virus, or Thogotovirus, Orthomyxoviridae, was first discovered in Kansas when a patient with a history of multiple tick bites died from an unknown infection.

According to the NC Medical Journal, the Bourbon virus has been detected in antibodies of white-tailed deer in North Carolina. The journal reports that the incidence of Bourbon infection in humans in this state is unknown but has likely gone unnoticed or possibly misdiagnosed.

The virus, which is linked to the Lone Star tick, is rare but can be fatal.

The Heartland virus was first discovered in Missouri in 2009, when two farmers with multiple tick bites were hospitalized for 10 to 12 days. One of the farmers fully recovered, but the other reported fatigue and headaches two years later, according to a 2013 report in the National Center for Biotechnology Information. The virus has now been found in seven states, including North Carolina. The virus typically requires hospitalization and can be fatal.

If that’s not enough to make your skin crawl, there is growing evidence that ticks may be responsible for causing an allergic reaction to beef, lamb, pork and other meat. Called Alpha-Gal Syndrome, people have a reaction to the tick bite several weeks after being bitten. Once the infection takes hold, a person will have an allergic reaction typically three to six hours after consuming meat. This delayed reaction often makes it hard for physicians to diagnose the problem.

The allergy is believed to be caused primarily by the Lone Star tick, which bites a person, sensitizing the victim to reacting to a type of carbohydrate found in the flesh of commonly-consumed meats.

Precautions urged

With the increasing prevalence of ticks in North Carolina, Barbarin and Herman-Giddens urge people to take the threat seriously and to take precautions, such as using insect repellent containing Deet, wearing long clothing, treating clothing and gear with permethrin and avoiding wooded or brushy areas with high grass and leaf litter.

After an outing in the woods, people should check their bodies closely for ticks, take a shower and wash their clothes.

The CDC estimates that 30,000 cases of Lyme disease are reported in the United States every year, about 10 times fewer than the number of cases that the agency believes actually occur. The number of reported cases has tripled in the United States since the late 1990s.

Despite those numbers, the N.C. General Assembly in 2011 abolished the Division of Environmental Health, which included the public health pest management section, severely limiting the amount of tick surveillance and public information efforts being done today in the state.

But a new pot of money that aims to improve the federal government’s response to tick-borne diseases became available late last year with the passage of the Kay Hagan Tick Act. The act is named after former U.S. Sen. Kay Hagan, a North Carolinian who died in 2019 after a lengthy battle with a rare tick-borne disease called the Powassan virus.

The act appropriates $150 million that will be used in the battle against ticks “to help expand research, improve testing and treatment and coordinate common efforts across federal agencies,” according to Lymedisease.org

North Carolina Health News is an independent, nonpartisan, not-for-profit, statewide news organization dedicated to covering all things health care in North Carolina. Visit NCHN at www.northcarolinahealthnews.org.

This article first appeared on North Carolina Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.