What were once green and lush lands have now turned into dry and dead fields. Orchards that have been passed down to farmers from generation to generation are being torn down because there is not enough water to keep them alive. Lakes, rivers and streams have shriveled away to cracked ground, shattered like broken glass.

This is the grim reality that California faces entering its fourth year of an extreme drought. In January 2014, Gov. Jerry Brown declared a state of emergency that included mandatory water usage reductions, some of which will remain in effect until at least May 2016. According to an economic analysis by an economist at the University of California Davis, the state’s 564,000 inactive acres of farmland will cause farm revenue losses of around $1.8 billion and economywide revenue losses of around $2.7 billion.

But what does a drought in California have to do with Western North Carolina? With California providing two-thirds of the nation’s produce and 80 percent of the world’s almonds, the drought has the potential to increase retail food prices throughout the country, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Local experts say the situation also holds lessons for food systems in WNC.

“California is a good cautionary tale of what happens when we concentrate a lot of agriculture in a small place on extremely large farms,” says Charlie Jackson, executive director of Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project. “The lesson of California is that a big centralized place where we’re growing most of the food for most of the country is extremely vulnerable and leaves us all very vulnerable.”

According to Marjorie McGuirk, founder of climate and weather consulting firm CASE Consultants International, much of the nation’s food production used to be in the Southeast. McGuirk explains that subsidies for irrigation, fewer native insect pests and improvements in irrigation techniques led to the shift from a distributed agricultural system to much of the nation’s agriculture being concentrated in the west.

The consequence of that change is an agricultural system where weather disruptions such as drought impact the entire national foodshed, says Laura Lengnick, a local author and former Warren Wilson College professor who works with the climate resilience consulting firm Fernleaf Solutions.

“When you have so much concentrated production in one area, you open yourself up to disturbances,” Lengnick explains. “It’s not a resilient system because if something happens in that one area, the entire U.S. food supply is affected.”

In addition to the more immediate impact at the grocery store, the drought in California may also be a harbinger of more food system disruptions. According to Lengnick, who recently wrote Resilient Agriculture: Cultivating Food Systems for a Changing Climate, this isn’t the last time we should expect to see climate change have an impact on national agriculture or local food production in WNC.

“[As] in most places in the country, climate change in this area is bringing more variable weather, such as warmer winters and more frequent and warmer heat waves and cold waves,” she notes. “The nights are getting hotter and interfering with fertilization of fruits like green peppers and tomatoes and squash, especially in the squash family. If nights are too hot, they stop producing female flowers and start producing male flowers, and male flowers won’t give you any fruit.”

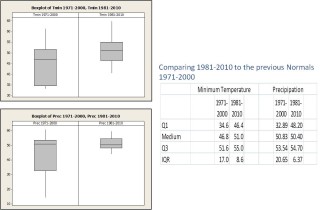

McGuirk agrees, saying data collected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is also showing changes in WNC’s temperatures.

“One of the stronger signals of climate change in WNC is nighttime temperatures,” she explains. “It’s not so much that we are warming up — though we are — it’s more that we’re not cooling off at night. The minimum temperatures are rising.”

While McGuirk notes that the different in high and low temperatures is slight, she adds that it doesn’t take much temperature change to begin to notice the effects. Rainfall has also changed — not so much in amount, but in severity. “It’s raining about as much as before, but it rains in bursts — ‘when it rains it pours,’” she says, explaining that we’re seeing less of the steady day after day rainfall WNC is used to having and more heavy rainfall.

The total amount of precipitation is about the same, but heavy rain has increased.

According to a report from N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources published in June, North Carolina may also experience the effects of a drought.

Lack of adequate rainfall and hot temperatures have pushed 20 N.C. counties in the central and western parts of the state into a moderate drought, and 51 other counties are abnormally dry — meaning they will be in a drought if dry conditions continue.

So how does a foodshed brace for the effects of climate change? Jackson says it may not be possible to predict the next instance of drought, flood or other extreme weather, but supporting a diverse local food network does create a more resilient system. Jackson explains that produce grown in many different places and different climates — where the plants are more adaptable because they are specific to that particular region — creates a system where “we’ll be stronger because we won’t have all our eggs in one basket.”

For WNC in particular, ASAP estimates that local farmers could produce as much as 40 percent of the fruits and vegetables the local community consumes, providing some protection from disruption caused by extreme weather in other parts of the country.

“Having farms in more diverse places, diverse climates, diverse sizes — that’s a resilience,” Jackson adds. “The work that we have been doing here in Western North Carolina is really happening all over the world, which is looking at having more diversity.”

According to Jackson, building resilience in agriculture has the cascading effect of building economic resilience as well. Consumers who support that network of local farms are also supporting local businesses and keeping more money in their own communities. It’s also often the case that those local farms tend to be smaller, independently operated and have direct ties to their consumers. A small local farm is more likely to respond to a community’s calls for increased wages or sustainable waste management, Jackson says, because the farm and its operators live and work within the community.

“Our consumption matters in that we make a choice on the kind of food system we want — large, centralized and vulnerable or decentralized, resilient and supportive of our values?” Jackson says. “By keeping food local and regional, we, as consumers and citizens, can create the food system we want, that responds to our values and beliefs — be they environmental, economic, social or all of the above.”

This isn’t to say that consumers should not support a national food system. Lengnick adds that the issue is more complex than simply buying local products and that consumers should try to strike a balance. “Farmers in California are hurting from the impacts of this drought,” she says. “I wouldn’t want to say stop buying California products because that’s the system we’re in and those farmers are depending on sales.”

But Lengnick says she believes consumers can drive a transition to more a resilient food system by using their own dollars to develop regional food systems and by advocating with politicians and the government to make policy changes that support those systems.

“A resilient U.S. food system would be made up of strong, diverse, local and regional agricultural economies,” Lengnick says. “There are some good ideas in resilience science for how to transform the system, but they’re mostly theories. I would say we want to proceed carefully, but we need to start working now to start transforming our system to be more resilient to climate risk.”

Lengnick adds that federal farm subsidies could be restructured to support small-scale, sustainable agriculture instead of industrial production of specific crops. In her book, she suggests this could include accounting for income and ability when distributing financial support so as to give more aid to new and developing farmers instead of encouraging the expansion of large, investor-owned agricultural operations. She adds that changes to the 2014 Farm Bill, including crop insurance options for organic growers and increased subsidies for beginning farmers, are noteworthy steps.

McGuirk notes that there’s another reason we should be thinking about our local food system: The slight increase in temperatures in the region, coupled with the reduced availability of water in California, may mean more large-scale production will be shifting back to the Southeast. “I see the biggest, long-term effect of climate change here as being a return to major food production in the Southeast, rivaling that of the West Coast,” McGuirk explains. “It will take investment in infrastructure, research in pest control and, most of all, adequate clean water. The Clean Water Act has been our friend in that regard.

“But, the way I see it, agriculture is ripe for further growth in WNC and elsewhere in the Southeast,” she continues. She points to research by University of Alabama climatologists that found that water in the West is overvalued relative to what can equally be derived from agriculture in the East. That research suggests the California drought could be an opportunity for under-irrigated states such as Alabama and other Southeastern states.

“If you’re going to irrigate a crop, you might as well irrigate it in the Southeast, where there’s water, rather than the Southwest, where’s there’s not,” McGuirk adds.

Jackson adds that part of localizing a food system is having consumers get in touch with the people who grow their food to let them know what kind of food they want to see produced in the region. It’s also a way to help people to gain a deeper understanding of the origins of the food that they purchase.

“[Food] is not just something that just shows up in a grocery store with no past or no real connections,” Jackson explains. “It’s something that’s very intimate and connected.”

Fantastic article. Over relience on California is a set up for trouble in the food supply. Local food has a lower cabin footprint and also boosts local economies. this was well presented.

Carbon footprint.

As we ARE in Appalachia, I think you had it right the first time.