Each semester, Tiece Ruffin, the interim director of Africana studies at UNC Asheville, asks her students to raise their hands if they’ve ever heard of Ellis Island. Almost all of them have. Located in New York harbor, it opened as an immigration station in 1892. From then until its closure in 1954, the site processed hundreds of thousands of new arrivals each year, most of them from southern and eastern Europe.

Next, Ruffin asks students to raise their hands if they’ve heard of Angel Island. At most, she says, a few students have; but typically, no hands are raised. Located in San Francisco Bay, the site operated as an immigration station from 1910-40, processing mostly Chinese and Japanese immigrants.

The survey, says Ruffin, drives home to her classes a key point: “We only know about Eurocentric history.” When it comes to America’s past, she says, people of color are often “relegated to the background — not held in a place of prominence; not shared in our K-12 or tertiary institutions.”

Along with several of her UNCA colleagues, Ruffin continues to push for a more inclusive narrative. She’s the lead organizer for 400 Years of African American Resilience, a five-day interdisciplinary series the university will host starting Sunday, Oct. 20. Through musical performances, historical exhibits, a film screening and a keynote address by renowned author and scholar Molefi Kete Asante, the series will honor African Americans’ contributions and struggles as part of a national movement commemorating the landing of the first enslaved Africans in England’s North American colonies in 1619.

In the coming weeks, a number of local individuals and organizations will mark this pivotal anniversary in various ways. Like Ruffin and her colleagues, these groups are looking to the past in order to promote a more equitable future.

The buried past

“As a white woman and historian who is very interested in my own ancestry, I am privileged to be able to trace it back generation after generation,” says UNCA history professor Ellen Holmes Pearson.

But for African Americans, such historical and genealogical road maps are far harder to come by, the historian points out. When their ancestors were stolen from their homelands, transported across the Atlantic, sold into slavery and given new names, entire histories were wiped out. “I can’t even imagine what it’s like to not really know where you’re from,” says Holmes Pearson.

Since the early 2000s, Holmes Pearson has worked alongside several other community members and educators to research and maintain the South Asheville Cemetery. Established in the early 1800s as a slave burial ground, it remained operational until 1943. According to Holmes Pearson, who’s a member of the South Asheville Cemetery Association, there are 2,000 bodies interred on the 2-acre property, the vast majority in unmarked graves. Volunteer groups help maintain the site, but more consistent maintenance is needed.

On Saturday, Oct. 19, from 10 a.m.-noon, DeWayne Barton, the founder of Hood Huggers International and co-founder of the Burton Street Community Peace Gardens, will lead the latest service day at the cemetery.

“They need some help out there,” says the entrepreneur and local historian. Along with removing dead vegetation and leaves, Barton will be trying to organize a regular maintenance program. The cemetery association, he says, is doing the best it can, and meanwhile, “We’re trying to get a more year-round calendar going, not only for cleanups but for people going out there to celebrate.”

For Holmes Pearson, Barton’s call for volunteers is a welcome chance to engage with new members of the community. Ongoing research at the site, the historian points out, could give some residents crucial links to their past. “For us to be able to uncover the history in the cemetery, and for us to be able to perhaps help some people at least find some of their ancestors — that is so important,” she says.

Harvesting history

The lack of documentation is a major research hurdle for the cemetery association. George Avery, a former slave owned by William Wallace McDowell, was the site’s first known caretaker. Born in 1844, he oversaw burials there from 1865 until his death in 1938. He left no known written documents. Much of what’s known about the cemetery’s past has come from oral histories.

Katherine Cutshall of the North Carolina Room at Pack Memorial Library has run into similar roadblocks while researching her 2019 online series, “52 Weeks, 52 Communities: A Journey Through Buncombe County.” As its title suggests, the blog examines the unique history of a different local community each week.

The process, says Cutshall, is a sad reminder of the dearth of documents concerning local African American history. Like Holmes Pearson, Cutshall sees the scarcity as a concrete example of white privilege. “Some of the posts I’ve done have been about my own family, and the information is really easy to find,” she says. “They weren’t particularly well off, my family, but that’s the privilege of being white: Your history is easy to find.”

In an effort to fill in some of the gaps in local African American history, Pack Library will host a pair of Saturday “History Harvests” on Nov. 9 and Nov. 23, from 1-5 p.m. On both days, black Asheville residents are encouraged to bring photographs, letters and other historical items to the library. The material will be scanned and returned to its owners that same day. Community members will also be able to sign up for future oral history projects that will be recorded and preserved in the North Carolina Room.

Rasheeda McDaniels of Community Engagement, an arm of Buncombe County government, is working closely with Cutshall to encourage participation. One of the challenges, McDaniels notes, is allaying distrust within communities of color.

McDaniels, who is African American, grew up in Stumptown, a historically black community near Riverside Cemetery. Many of the homes in the area were razed during urban renewal and never replaced. Her family ties to the region, she says, help her bridge the gap between the city’s African American communities and historically white institutions.

As of this writing, 20 residents have committed to attending the events, she says. Each of these individuals has been encouraged to invite 10 additional people; if they do and all those invitees decide to participate, the library could end up preserving more than 200 individual and family stories for future generations.

“I remember growing up with my granny,” says McDaniels. “And I just wish I could hear her voice again or see pictures. That’s why this is an important project to me: Preserving that history is just a wonderful gift that you can give someone.”

Honoring Johnny Baxter

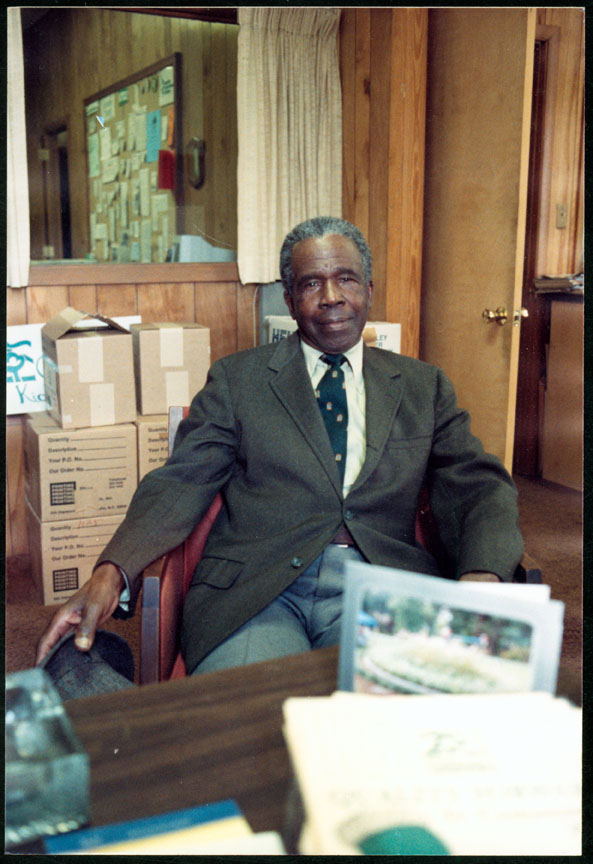

Like Cutshall and McDaniels, the Preservation Society of Asheville and Buncombe County is also in the midst of expanding its outreach. This summer, the organization introduced the Johnny Baxter Award in partnership with UNCA. The annual grant will provide $500-$1,000 to a student who’s doing something to further the study of African American contributions in Asheville and Buncombe County.

Jack Thomson, the Preservation Society’s executive director, says the award was developed to honor founding board member Johnny Baxter, who grew up in Chunns Cove and was the descendant of slaves. In 1977, Baxter played a crucial role in adding the YMI Cultural Center to the National Register of Historic Places; at the time, developers were eagerly pushing to transform the core of Asheville’s downtown into a mall.

UNCA senior Brooke Mundy, a history major, is the award’s inaugural winner. Working with several community partners, she’s gathered information on local African American women. In the summer of 2018, Mundy spent days scouring local historic sites, archives and museums to document pertinent material. She’s currently working on creating a database, summarizing the content and noting where the various items are located. Ultimately, the project will also include a website.

In addition, the Preservation Society recently awarded a $5,000 grant to the South Asheville Cemetery Association to help cover the cost of nominating the cemetery for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places.

“We obviously should have been working on this much harder, much earlier,” says Thomson. “We’re playing catch-up, taking the steps that we can, especially now since the organization has grown.”

Spotlighting institutional racism

On Dec. 21, 2017, the 400 Years of African American History Commission Act cleared Congress. Among other initiatives, the bill encouraged “civic, patriotic, historical, educational, artistic, religious and economic organizations to organize and participate in anniversary activities.”

But even before the bill’s passage, a growing desire for a more inclusive history was evident. Michelle Alexander’s 2010 book The New Jim Crow and Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption in 2014 both became New York Times bestsellers.

Meanwhile, in 2016, ESPN aired the five-part miniseries “O.J.: Made in America.” The special chronicles the life, career and criminal trials of football star O.J. Simpson; the series also explores racial tensions and conflicts that erupted in the United States throughout this period.

Shortly after “O.J.: Made in America” debuted, Netflix aired its original documentary 13th, which analyzes the criminalization of African Americans. The film connects today’s mass incarceration to a clause in the 13th Amendment that prohibits slavery and involuntary servitude “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.”

“The thing about historians is we’re always shaped by what’s going on around us,” says Steven Nash, president of the Mountain History and Culture Group, a nonprofit providing support for the Zebulon B. Vance Birthplace.

In 2013, Black Lives Matter emerged following the death of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed black teenager shot to death by neighborhood watch volunteer George Zimmerman. Zimmerman was found not guilty of second-degree murder. Many local scholars, including Nash, say the grassroots organization has shaped present-day conversations about systemic racism and police brutality. In the process, scholars maintain, the movement has pushed citizens to more closely examine the country’s history of institutional racism, often shifting how we interpret the past.

Identity crisis

In December 2017, vandals painted “Black Lives Matter” on the log cabin at the Vance Birthplace; faint red lettering is still visible. “At this point now, it’s a part of the story of the site,” says site manager Kimberly Floyd.

The vandalism, she says, has empowered her to continue taking the site in a new direction, which she’d been attempting to do since her arrival in June 2016. Today, the historic property’s guided tour focuses primarily on the lives of the Vance family’s slaves and “what life was like among early 1800 plantations in Western North Carolina,” Floyd explains.

But that approach, she notes, sometimes generates pushback. Some visitors arrive unaware that slavery existed in Western North Carolina. Others, who associate plantations with the Deep South, assume that the property’s lack of grand antebellum architecture somehow diminishes the cruelty behind the Vance family’s ownership of 18 human beings. The “benign slave owner” trope is yet another response. And in one case, a schoolteacher called in advance insisting that slavery not be discussed during her class’s upcoming visit; the site didn’t honor the request. Still, most visiting school groups and teachers embrace the site’s full history, stresses Floyd.

“When someone comes here, they may not have reckoned with the fact that Vance was a white supremacist or what that even means,” she explains. “The uncomfortable part for them is questioning their own identity. … So the pushback is coming because we’re sometimes forcing people to reckon with that.”

In a way, the Vance Birthplace and visitors’ mixed responses to it are a microcosm of the country as a whole. As many scholars who spoke with Xpress note, America has yet to truly address the ongoing legacy of slavery.

Resilience and perseverance

For Ruffin, connecting the past to the present is crucial. Speaking about the upcoming 400 Years of African American Resilience commemoration, the UNCA professor says, “One of my goals is that we recognize the past so we can understand the legacies of inequalities today and how race is still central.” Mass incarceration, the school-to-prison pipeline, inequities in housing and disparities in education and health are among the ways our country’s history manifests in the present day, she points out.

Another goal is encouraging activism. “We are not in a post-racial America, therefore we still need people to work as freedom fighters and social justice advocates,” argues Ruffin. Social media posts are not enough, she says: Action is required, and it must begin at the local level.

Darin Waters has a similar take. An assistant professor of history at UNCA, he organizes the annual African Americans in WNC and Southern Appalachia Conference.

Change, maintains Waters, “has to really happen locally first. I think America is kind of structured that way. … And then you kind of create a wave.”

That action can take many forms, notes Ruffin. Engaging with community members, volunteering with organizations that work to dismantle racism or making a donation to a nonprofit that’s working along those lines are three easy ways to get involved, she says.

But above all, Ruffin sees the upcoming interdisciplinary commemoration as a celebration of African American resilience and perseverance in the face of monumental odds and horrific cruelty. “I don’t want people to be sympathetic, but I do want people to see that we are fully human,” she says. “Don’t see African Americans from the deficit perspective, because we have made contributions to this great nation.”

At-large elections are a form of minority suppression…

LOL no they’re not. What it really is that voters aren’t electing minority candidates because for the most part they have nothing to run on. Maybe minority candidates should run on I don’t know, spending less, lowering taxes, and jobs. Instead we get racial blaming, excuses as to why many are becoming unteachable.in school, and simply wanting more money. And guilting others into paying it. Run on something besides divisions. And in fact start calling out the destructive behaviors and lack of parenting participation for the state of certain people . But that would merit said minority candidates shunning from the ones they want to represent. After all what minority would vote in someone that tells them to help themselves before expecting others to help them?

Interesting the Masonic Compass and Square engraved on that tombstone!