Three-letter acronyms are commonplace in modern English parlance, signifying anything from an airport destination to a sports team or a figure of speech. But for folks living near Mills Gap Road in South Asheville, the letters “CTS” might evoke any number of things: grief, frustration, suspicion or even hope.

For the better part of three decades, neighbors, activists, local media, scientists and government officials have been embroiled in a heated debate over what to do about the dangerous levels of trichloroethylene, or TCE, emanating from the CTS of Asheville Superfund site — and who’s to blame for letting it go unaddressed for so long.

In one sense, the community’s ongoing struggle is a model of grassroots civic engagement, as residents with varied backgrounds banded together to push for cleanup and accountability. Yet it’s also a cautionary tale of how a toxic mix of hazardous chemicals, government bureaucracy and differing priorities can tear a neighborhood apart.

With the Environmental Protection Agency finally taking steps aimed at eventually eradicating the source of the contamination, some key players hope the deep social divisions created by the CTS saga can finally begin to heal. Others, however, say the scars left by this divisive history will remain until justice is served for those who have suffered the most.

“Something wasn’t right”

It began with a phone call. In 1990, Dave Ogren noticed that his friend and neighbor Larry Rice Sr. had missed several meetings of a community zoning committee they both served on.

“I ran into [Larry] one morning at the gas station,” Ogren recalled in a 2016 interview with Xpress. “He said he’d been sick, that something wasn’t right. He said he thought it was their water, but he had no idea.”

Ogren’s concern deepened when, soon afterward, he was having some work done at Arden Electroplating (which operated out of the former CTS facility) and glanced out the back door.

“There were all these barrels — countless barrels — and this big pond that was blue-green in color and shimmering, no weeds growing through it,” remembered Ogren. “I got to the edge, where there was a fence between CTS and the property down the hill, and said, ‘By God, that’s Larry’s house down there.’ That was his problem!”

Ogren did what any concerned citizen might do: He called county, state and federal environmental authorities.

“I knew the place was for sale at the time and wanted to make sure that the old owner or somebody was going to clean it up before it got sold, and that would fix up Larry,” Ogren explained. “I thought, OK, problem solved: Everybody will show up and clean it up.”

Poisoning the well

Most of the 57-acre site had been sold to a local partnership several years earlier. But despite Ogren’s efforts and subsequent tests that showed dangerously high levels of TCE and other contaminants in and around the CTS property, neither the EPA nor the state notified the Rices or other nearby residents about the contaminants they were consuming, bathing in and letting their children play in.

Fast-forward to 1999, when the Rices called the EPA to report a foul smell emanating from the spring that supplied their drinking water. Testing revealed TCE concentrations of 21,000 parts per billion — thousands of times higher than the limit considered safe.

Becky Robinson, a neighbor, tells a similar story. “The way it came to our attention was EPA came by, knocked on our door and told us they needed to sample our well,” she recalls. “They came back a couple days later and told us that our water was contaminated, that we couldn’t use it for bathing, drinking, washing clothes or anything. They had found the contamination years before but just assumed everybody in this area was on city water.”

While the two families were quickly hooked up to city water lines, nothing was done to address the contaminants seeping from the former CTS property into the groundwater. And meanwhile, the local partnership had sold about 45 acres in 1997 to a developer who built the Southside Village subdivision.

Watershed moment

For years after that, little was done to address the groundwater contamination. The EPA did install a vapor extraction system in 2006, but it only addressed pollutants near the soil surface. The following year, however, Larry Rice’s cousin, Weaverville resident John Payne, reached out to a neighbor for help.

“He knew I had a chemistry background, so he asked me to go check out where his cousin lived,” says Barry Durand, a central figure in the early community response to CTS. Durand took several samples from surrounding streams to the Environmental Quality Institute at UNC Asheville for testing; 10 different known or suspected carcinogens were found, including TCE.

Like Ogren before him, Durand sought help from the State Bureau of Investigation, but the SBI’s interest in the case quickly waned. “Basically, they said they couldn’t do anything, because the statute of limitations had probably gone too far,” says Durand. SBI investigators did have a suggestion, however: “It was their recommendation that I get it published somewhere.”

So, in the spring of 2007, Durand contacted Mountain Xpress and began working with reporter Rebecca Bowe. In July, Xpress published a lengthy story titled “Fail-Safe?” that explored the contamination issues around the site, the lack of government oversight and the subsequent development of Southside Village.

Durand calls the article a “watershed moment” in the long-running fight, galvanizing the community and sending environmental regulators scurrying to address the problem.

E pluribus unum

Despite the EPA’s continuing assurances that the situation was under control, Durand and others say little was being done to address groundwater contamination or hold CTS accountable for the mess. So in 2007, frustrated community members came together to begin monitoring the federal agency’s activities and demand a cleanup.

It was a heterogeneous group. Aaron Penland’s family had worked at the CTS plant for years prior to its closing in 1986; many of them later suffered from cancers he believes are linked to TCE exposure. Bob and Judy Selz, homeowners in Southside Estates (another nearby development), were appalled by the lack of information available about the contamination issues. Tate MacQueen, who would subsequently become a driving force in the group’s efforts, found out about the issue via a flyer left in his mailbox.

“We had a diverse background,” MacQueen recalls. “We had staunch conservatives who care about the environment; we had aggressive progressives; we had males and females, old and young.”

The common bond, adds Durand, was simple: “We’re all interested in our neighbors’ well-being.”

The politics of action

The community’s calls for action and frustration with the EPA’s slow response soon caught the ears of legislators across the political spectrum, from the local level all the way to Washington.

“We’ve had consistent involvement from Sen. [Richard] Burr, [Rep.] Heath Shuler’s office; [Sen.] Kay Hagan’s office, [Rep.] Mark Meadows,” says MacQueen, rattling off the names of past and present lawmakers like items on a dinner menu.

Pressuring elected officials is a key strategy for communities trying to get hazardous waste sites cleaned up, says hydrologist Frank Anastasi, who’s served as a technical adviser/community liaison for a host of Superfund sites, including CTS.

“It takes citizens almost embarrassing elected officials into seeing that the bureaucrats aren’t doing what they’re supposed to,” Anastasi maintains. “When elected officials see that their constituents aren’t being treated or protected like they’re supposed to, they make the bureaucrats shape up.”

For former state Rep. and former Buncombe County Commissioner Tim Moffitt, the CTS issue literally hit close to home. “I’m in the 1-mile perimeter of the site,” says Moffitt, who, along with other former county commissioners and former county manager Wanda Greene, was instrumental in getting Buncombe County to install city water lines for residents within a mile of the CTS property, despite opposition from EPA officials, CTS and even some community members, who favored installing water filtration systems.

Alongside state Rep. Susan Fisher, a Democrat, the Republican Moffitt also spearheaded a select committee to investigate federal and state agencies’ handling of the site, catching the attention of national media outlets and further publicizing the issue.

By 2012, the EPA had officially added CTS of Asheville to its list of the most contaminated hazardous waste sites in the country. Moffitt credits community members with bringing the issue to the forefront, saying, “I was pleased to play a role in that, but it was a community effort, by far.”

Shining a spotlight

Local media have also played a crucial role by providing consistent coverage of the issue, notes MacQueen. In addition to reports by Xpress, the Asheville Citizen-Times and WLOS, the CTS site was the subject of the 2014 documentary My Toxic Backyard, by local filmmaker Katie Damien. But it was the residents, she stresses, who “just never quit. They never stopped trying to get the word out, trying to get people talking and thinking about it.”

Former WLOS investigative reporter Mike Mason, who produced an hourlong special in 2013 titled Buried Secrets, says the story was “one of the most important and troubling” of his 18-year career.

“This issue was like the movie Erin Brockovich on a smaller scale, but with the added government-corruption angle,” he says. As part of its investigation, WLOS leveraged the Freedom of Information Act to obtain 62,922 pages of documents, which Mason says “exposed major issues” in the EPA’s handling of the site.

The combination of well-timed media reports and dogged activism also prevented the site from being placed in the brownfields program, notes Durand, which would have capped the total amount that all responsible parties could be required to spend on a cleanup at $5 million. In addition, the move would have indemnified those companies from responsibility for any future issues related to the contamination.

“CTS’ name would be disconnected,” he says. “It’d be this nondescript Mills Gap Groundwater Contamination site,” and the responsibility for further remediation “would be put on the neighbors next door. But the original site wouldn’t be cleaned up, and we’d still be breathing this stuff.”

Who watches the watchmen?

MacQueen, Durand and others see the EPA’s defensiveness and lack of transparency as nothing less than a criminal attempt to cover up past misdeeds.

“They have not held anyone accountable,” says MacQueen. “No demotions, no firings, no accountability or criminal charges. At the end of the day, this is an environmental justice issue: It’s part of what we fought for, and that remains without conclusion.”

Damien, meanwhile, says that while making her film, she saw an agency hamstrung by fiscal constraints and other legislative obstacles. Until 1995, the Superfund program was financed by taxes on petroleum products, hazardous chemicals and corporations that produced waste, according to the EPA’s website. Those moneys were used to remediate sites and go after polluters in court.

But in 1996, Congress rescinded the tax, choosing to support the program through allocations from the general revenue fund. The EPA has repeatedly asked Congress to reinstate the Superfund tax, but lobbyists for industrial interests have vehemently opposed the idea.

And whatever the reasons for the EPA’s lack of response, it fostered deep mistrust among residents, says Damien.

“What do you do as a citizen when you’ve said you’re worried about this thing and someone comes out, tests it and says, ‘You’re fine.’ You’ve already gone to the federal government — who else are you supposed to turn to?”

A fractured front

Meanwhile, even as official investigations into the handling of the site were underway and residents were gearing up to battle CTS in court, cracks were beginning to show in the community’s united front.

“The vibe several years ago was tense,” remembers Mason, the former WLOS reporter. “The two [community action groups] were at odds. … Most Southside Village residents wanted to hear nothing negative. Many residents felt like they had entered a rabbit hole that was 6 feet deep.”

According to MacQueen, “There were two fractures that left three pieces. The first fracture was instigated and implemented by the EPA talking to the [Southside Village] residents about what would happen to their property values if they were folded into the Superfund site.” Up until then, says MacQueen, those residents had mostly sided with the Mills Gap Road activists. Since then, they’ve tended to take a more hands-off approach, citing a 2015 letter from Region 4 Superfund Director Franklin Hill and periodic test results to bolster their contention that their neighborhood is safe and property values are holding steady.

The second fracture, several residents say, occurred when members of the original community advisory group split off and formed a separate entity called Protecting Our Water and Environmental Resources. Durand maintains that POWER’s softer stance toward the EPA weakened the original group’s ability to hold the federal agency’s feet to the fire. POWER co-founder Lee Ann Smith says her group was formed in order to approach the CTS issues with a fresh outlook that has paid dividends on a number of fronts.

Jeff Wilcox, an associate professor of hydrology at UNCA who began regularly taking his classes out to study the CTS site in 2008, says he initially viewed the creation of a second group optimistically. “I thought, What’s the problem with the two groups trying two different tactics? Let’s surround them!”

But that optimism quickly dissipated. “It ended up — because of the personality conflicts between the two groups and, maybe, the tactics used by both sides — becoming a pretty toxic thing in itself,” says Wilcox, who serves as a technical adviser to the residents, regardless of which group they’re affiliated with.

TAG or gag?

A persistent sore spot between the two groups has been POWER’s acceptance of a $50,000 EPA technical assistance grant. Funded by what the agency calls “potentially responsible parties,” these grants enable communities to get help with interpreting site data and communicating with agency officials.

Members of the original community group say they turned down the technical assistance grant because of clauses that would have restricted their ability to question the EPA’s actions. POWER, however, used the TAG money to hire Anastasi, who, like countless others involved with the CTS site, was puzzled by the EPA’s lack of action to address contaminants.

“We were told that we can’t push CTS too hard, because we only have a limited amount of money, and if we push them too hard, they might not agree to do anything,” Anastasi recalls. “When we looked and said, ‘What are they actually doing that you’re afraid they’ll stop doing?’ there wasn’t a very good answer.”

Still, Anastasi says he was surprised by the depth of animosity between the two community groups. “This is the only community I’m aware of where you had two sets of people that are kind of pitted against each other,” he says. “It’s almost like the Hatfields and McCoys. I understand it at CTS, though: It’s not a great situation for anybody.”

For his part, Anastasi says he’s here to help residents, regardless of which group they’re affiliated with. “I don’t have a personal stake — I’m not a Hatfield or a McCoy. Anyone who wants to contact me and ask me anything about the site, I’ll be glad to give them my perspective and try to answer their questions.”

Simmering tensions

Relations among the various community factions have remained strained at best, fueled at times by outside instigation and sniping by community members.

“I think that everybody who’s been involved, including me, would do some things differently if given a chance,” says Wilcox. “It’s not been helpful to have a community group splinter and attack each other.”

In the ensuing years, the two groups have clashed over various issues, ranging from personal grievances to differing interpretations of the EPA’s remediation proposals. In 2013, the acrimony had become so bitter that MacQueen and Smith resorted to a legal agreement that prohibits communication between them or any members of their respective families. Both sides declined to discuss the issue, saying they have moved on.

Last winter, however, tensions bubbled to the surface when the North Carolina Wildlife Federation honored Smith with its Water Conservationist of the Year award. In its initial press release, the federation credited Smith with discovering the contamination and conducting the research on the site, with no mention of the work other community members had done.

Smith says she didn’t know she was getting an award, had nothing to do with the press release, and acknowledged in her acceptance speech that it was a community effort. The federation has since amended its description of Smith’s involvement, but Wilcox says the initial misattribution revived old grudges and distracted community members from the deeper issues they should be focusing on.

“Rather than ‘Hey, there’s finally going to be a cleanup; we just need to hash out access agreements,’ all anybody could talk about was this damn award,” says Wilcox. “That really was a disservice to the community, to give an award based on false pretenses.

“I almost want to tell somebody who’s new to this not to get involved,” Wilcox adds. “It’s too convoluted; it’s too intense.”

Good news, bad news

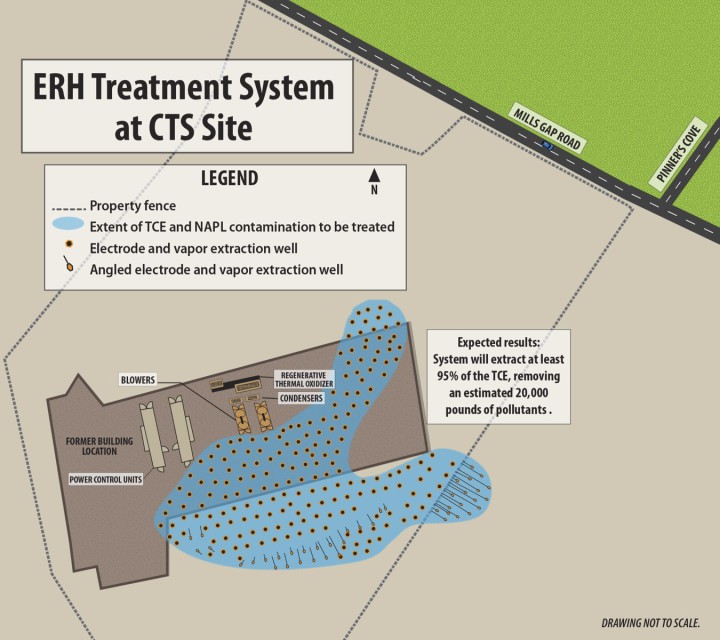

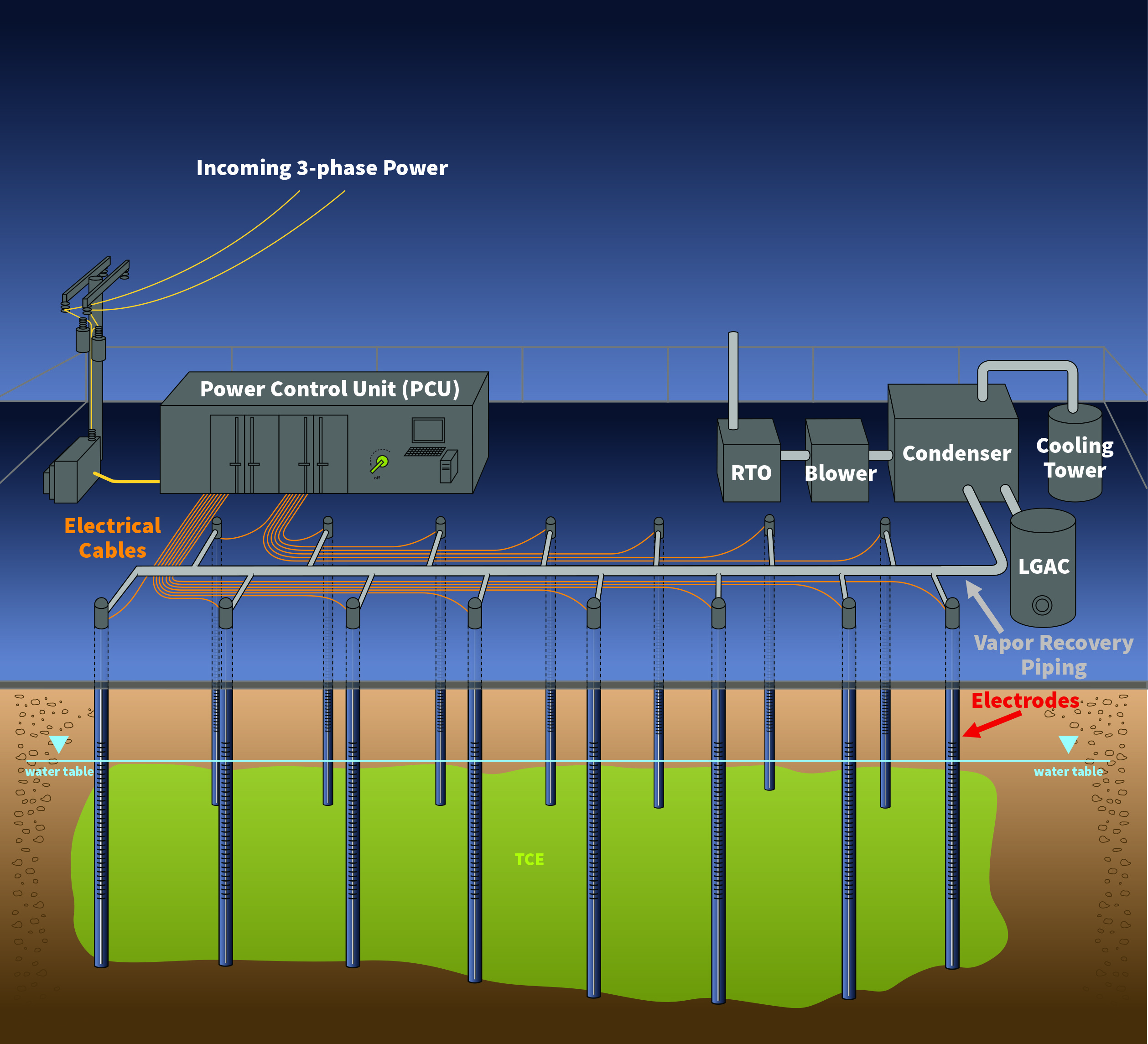

Despite continuing community dissension, cleanup efforts have proceeded since the EPA and CTS agreed on an interim remedial strategy in 2016. Contractors are currently installing an electrical resistance heating system that, beginning in May, will treat a roughly 1-acre area identified as the source of the contamination. Treatment is expected to take 90-120 days. Next year, the EPA will employ a different technology — in situ chemical oxidation — on an additional 1.9 acres at the site (see “In Situ Remediation Could Revitalize Hazardous Waste Sites,” Feb. 23, 2017, Xpress).

EPA officials say the scope of the current cleanup efforts and the safeguards being put in place reflect community concerns and feedback. “Specifically, [that] hand-held vapor meters will be used to screen the air for volatile organic compounds, including TCE, around the drill rigs and the soil roll-off bins, as well as around an outer perimeter of the work zone, during installation … and operation of the system,” Davina Marraccini, EPA public affairs specialist for Region 4 said in an email to Xpress.

Once these interim strategies have been completed and further testing is conducted, the EPA will explore a full remedial plan to address TCE that has leached into the fractured bedrock, agency officials say.

But however successful those efforts prove to be, residents suffering from serious health issues say the damage has already been done. Larry Rice Sr. has a brain tumor; his wife, Dot, their children and grandchildren have all dealt with various cancers and other maladies, as have members of the Robinson family and other community members (see “Toxic Legacy: CTS Site Breeds Heartache For Residents,” June 1, 2016, Xpress). Despite residents’ suspicions that these health maladies were caused by exposure to the CTS site contamination, “proving such causality is extremely difficult,” wrote Lenny Siegel, Executive Director of the Center for Public Environmental Oversight, in a 2009 report on the CTS of Asheville site.

“It’s awesome that they’re going to pull out or mitigate the contamination that’s sitting above that bedrock, but there’s nothing they’re ever going to be able to do to bring back what’s been released,” says MacQueen. “It’s like saying, after a football game, ‘We lost, but we gained four yards! Go, team.’”

Lessons learned

What lessons have community members drawn from this long, complicated history? As with so much else surrounding the CTS site, the answer depends on whom you ask.

The EPA says its experiences with the site informed revisions to the agency’s public-engagement policies. “These guidelines have greatly improved EPA’s communication with property owners/tenants throughout the Southeast whose homes are sampled as part of the Superfund investigation process,” Marraccini wrote.

Over the years, there have been several investigations by the EPA’s Office of Inspector General that criticized the agency’s handling of the case, cited progress in some areas and pointed out where improvement was still needed. According to MacQueen, the inspector general launched a criminal investigation in April 2012 that was still ongoing when he met with investigators in 2013 and again in 2015. Asked about the current status, Jennifer Kaplan, deputy assistant inspector general for congressional and public affairs, said the investigation was officially closed in March 2017. She was unable to provide any further information.

For his part, Wilcox feels that educating your community and continuing to speak up are keys to getting regulators to act. “If you have a community meeting and it’s standing room only, and people are pissed and asking questions all night long, it gets people’s attention,” he notes, adding, “That doesn’t happen if it’s just one person.”

Durand sees the battle over the site as emblematic of a bigger issue: the need for communities to actively demand a cleanup rather than just trusting that government agencies will take care of things. “Communities can be affected; I think we’re the model for it,” he says. “Yes, you have interpersonal things that happen, but you have to work around them.”

Smith, meanwhile, says she hopes CTS of Asheville will serve as a warning to other communities “so one day pollution will cease, and no one will get sick from drinking their water or playing in their own backyard.”

And despite all the setbacks, infighting and frustrations, stresses MacQueen, one key factor has remained central to his group’s continuing struggle. “The victims who are actually impacted have been the source of our inspiration, our strength, our energy and dedication,” he points out. “With Dot Rice and her family, and now Becky and her family — we’ve been there for each other.”

This is a great piece, Max, and it reminds us of the journalists who did the hard work on this story over the past decade — and why local journalism matters.

This is, once again, a story about externalities: Northrop Grumman and CTS might not have known about the long term effects of dumping carcinogens into the groundwater where people relied on wells, but they certainly didn’t care enough to find out, and whatever happened in the future would be somebody else’s problem. In addition, as we’ve seen over the past year and a bit, the EPA can too easily be turned into a polluters’ plaything.