Editor’s note: Names of the homeless individuals quoted in this story have been changed to protect them from discrimination by potential or current employers.

On a frost-laden December morning, groups of homeless folks huddle outside the AHOPE Day Center on North Ann Street. Some engage in lively conversation; others wrap Christmas presents on a picnic table outside the facility. Still others sit off to one side, silently enjoying a cup of coffee and maybe a cigarette as they try to shake the previous evening’s cold from their bones.

“Darnell” came to Asheville two months ago to escape harassment by the authorities in Greenville, S.C., where he was living in his tent. “They like to round you up and kick you out into the county,” he says. “They’ll give you a few weeks, and if you’re not gone, you’re going to jail.”

Darnell is a jack-of-all-trades. “Carpentry, flooring, landscaping — I’ll do it all,” he says, adding that he’d like to find a steady job rather than working through temp agencies. “Anything that requires me to travel far won’t work: There’s no transportation.”

Rules at shelters vary, but many limit how long a person can stay. And when no shelter space is available, homeless folks must fend for themselves, staying with friends, camping out in tents or simply bundling up against the elements as best they can.

In 2005, the city adopted “Looking Homeward: The 10-year Plan to End Homelessness in Asheville and Buncombe County.” Through a cooperative effort involving local nonprofits as well as city and county governments, the plan aimed to effectively end “chronic homelessness” by 2015, drastically reduce reliance on emergency shelters to care for those living on the streets and streamline support services to get people into permanent housing faster.

Ten years later, questions linger concerning the program’s results. Although chronic homelessness has been curtailed substantially, the combination of a severe economic downturn, an acute shortage of affordable housing and the rising cost of living has hindered the overall progress. Despite those setbacks, however, partners in the project are forging ahead with new initiatives to combat housing insecurity and ensure that those in need of shelter get it.

Great expectations

As of 2005, an estimated 2,000 people were experiencing homelessness in Asheville and Buncombe County at some point during the year, according to the 10-year plan. And with appropriate support, most of them (80 percent) were considered likely to find housing and get back on their feet in a matter of months.

Meanwhile, the chronically homeless — about 10 percent of the homeless population — accounted for more than 50 percent of the resources used, consuming hundreds of thousands of taxpayer dollars annually to cover things like emergency room visits, jail time and emergency shelter sojourns.

To create a streamlined path from the streets into permanent housing, the Homeless Coalition, comprising city and county officials, business owners and representatives of local nonprofits, devised the 10-year plan in 2004.

It outlined several goals: reducing the number of people becoming homeless; expanding permanent housing options for the currently homeless; decreasing the amount of time people had no home; and implementing pre-emptive services to prevent future cases of housing insecurity. More transitional housing and day programs would be established to replace emergency services, access to support services would be streamlined, and the overall cost of serving the homeless population would shrink.

Perhaps the largest and most radical component was a shift from making mental, physical and financial issues the No. 1 priority to a “housing first” model. Citing numerous studies conducted across the country, the plan’s developers believed providing housing first was a better way to help people in need.

The idea was to facilitate self-sufficiency while also ensuring that clients’ medical and social needs were met. More importantly, the homeless would be involved in the process, having a say in both where they were placed and how long they remained there.

Making headway

Ten years later, partner organizations say they’ve achieved several important victories. “We’ve seen a dramatic reduction in chronic homelessness,” says Brian Alexander, executive director of Homeward Bound of WNC. The nonprofit provides basic support services through AHOPE while helping place individuals in permanent housing.

Overall, Buncombe County’s homeless population has declined by almost 25 percent since the ten year plan was implemented, says Alexander. “First, we’ve seen best practices such as housing first, supportive housing and coordinated assessment embraced by the community as the most effective and humane ways to serve individuals and families experiencing homelessness; second, the community has created a system of care, working together on this issue rather than working separately as individual programs.”

A key starting point for these efforts is AHOPE. Besides the baseline services provided there — a hot shower, storage for belongings, phone and mail access, food and shelter from the elements — the day center also serves as a point of entry for those seeking housing assistance, says Beth Russo, Homeward Bound’s director of communication and annual campaign.

“After people qualify for our housing services — usually some form of financial assistance, such as rent and utility deposits and rental assistance, as well as case management services — we work to get them into permanent, affordable housing,” she explains. “That’s a real challenge in our community, but we’ve been able to move over 1,300 people into permanent housing since we adopted the housing first model and have an 89 percent retention rate — meaning 89 percent of the people we’ve moved into housing have stayed there,” Russo reports.

Other project partners also cite major strides in several key areas. “In 2003, we averaged nearly 700 homeless persons” on any given day, says the Rev. Scott Rogers, executive director of the Asheville Buncombe Community Christian Ministry. Since then, he says, ABCCM and its affiliates have added a significant number of both emergency and transitional beds to their facilities.

Rogers credits improved collaboration among agencies with effectively reducing the number of chronically homeless individuals — a model he says has been held up as a standard for communities across the country. “Different organizations have tried to do what they do best. ABCCM has focused specifically on housing about 220 veterans a day through a multipronged approach.” This involves both finding affordable permanent housing for clients in transitional housing and “providing the kind of employment training and services that lead to living-wage jobs.”

The new normal

“Paulie” introduces himself as “the new breed of homeless people.” Before the Great Recession, he owned his own flooring business. “A lot of people who used to be considered middle class are living on the streets now,” he observes. “I’m not what people expect: I work hard; I have knowledge about things and plans.”

An Asheville resident for several months, Paulie has a regular job. But he says past employers have treated him differently when they found out he lived in a shelter.

At the same time, Paulie criticizes the indolence he sees in some members of the homeless community. “People have been docilized,” he says, gesturing toward the breakfast station. “They’re taught to go try to get on disability at a young age. Even here, people grab up their doughnuts and processed sugar. It’ll keep you alive, but it doesn’t give your body what it needs.”

While we talk, another AHOPE client approaches. “You reporters come down here asking questions about what it’s like,” he says, laughing sarcastically. “You can ask him or me or whoever all the questions you want, but you can’t explain it to someone who hasn’t lived it.”

The man saunters off, but not before offering one last piece of advice: “Go camp outside in 20-degree weather for a week, and then ask yourself those questions. You’ll see what it’s like then.”

Paulie shrugs his shoulders. “That guy’s just mad,” he says apologetically. “The cold weather gets people on edge.”

The best laid plans…

“Attempting to ‘count’ homeless folks is notoriously slippery,” notes the Rev. Amy Cantrell, a member of the Be Loved Community who’s worked extensively with homeless people in Asheville and other cities. “Often the counts are done where folks access services, so if someone chooses not to utilize AHOPE or a shelter, they may not be counted. It’s done on one particular day, so transience plays a role. And then there are whole segments of folks ‘doubled up’ with friends, relatives, etc., who are often not counted and are one of the more invisible segments of the homeless population.”

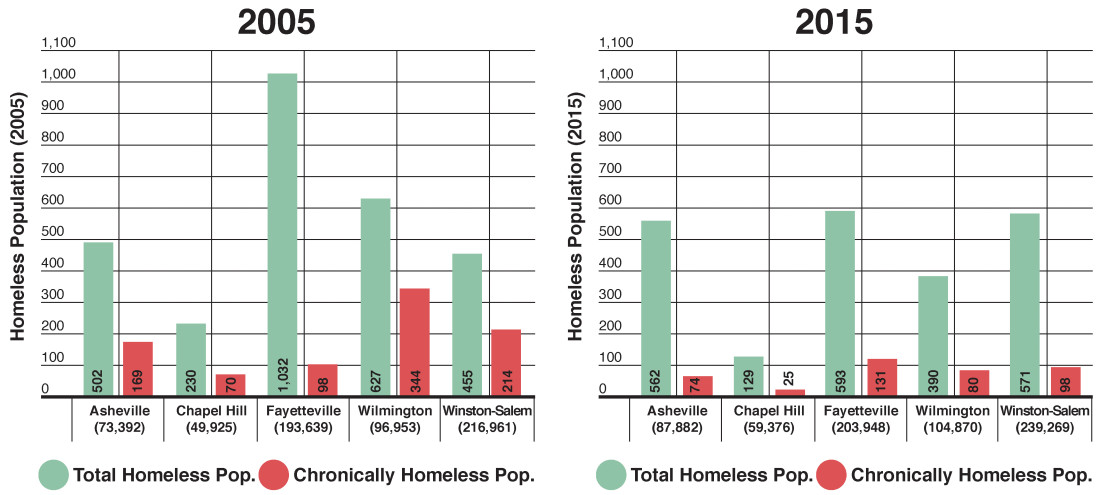

Judging by the annual point-in-time counts, however, the average local homeless population has dropped from 689 in April 2004 to 562 as of last January, including those folks in shelters or transitional housing. But that actually represents an increase over the 2014 figure (533), notes Christiana Glenn Tugman, the city’s homelessness coordinator. Meanwhile, the number of chronically homeless has fallen from 169 in 2005 to 74 today, a 56 percent drop.

“In many ways, the 10-year plan, with its housing first model, was working well,” says Cantrell. “I saw a great decrease in the number of folks on the street, particularly those who where considered chronically homeless.”

But the 2008 recession dealt the plan a major blow, she notes, sending many residents who’d been living “paycheck to paycheck” into a housing crisis. “I met nurses and truck drivers and folks who worked for the airlines and other professionals” living on the streets, she reports.

The significant decrease in chronic homelessness over the last decade, she says, has been offset by the rising numbers of people in emergency shelters and transitional housing. Among that population, the underlying causes of homelessness — mental illness, domestic violence and substance abuse — remain core factors.

“I’ve seen chronically homeless people return to the streets because they didn’t have enough community support,” says Cantrell, whose group places a premium on strengthening the connections between the homeless and community support services.

Meanwhile, she continues, “We face almost all the progress of our 10-year plan being wiped away due to a serious affordable housing crisis. It’s difficult to do the housing first model when you have no houses to move people into.”

To illustrate this, Cantrell cites a chilling statistic: 50 percent of the local homeless folks found dead last year due to exposure had a housing voucher on their person. “This is shameful,” she exclaims. “We are currently over 5,000 affordable housing units shy of what we need to meet the need for housing, according to the Bowen report.” The 2014 housing needs assessment by consultant Patrick Bowen covered Buncombe, Henderson, Madison and Transylvania counties.

Alexander concurs. “While there is some cause for celebration, we have some important issues to address.” In the past 10 years, he says, the number of veterans among the total homeless population has risen from 126 in 2005 to 209 in 2015. Most are currently in transitional housing. “Buncombe County has the region’s only VA Medical Center for veterans in crisis,” Alexander points out. “The community also has the nation’s third-largest transitional housing program for homeless veterans, which draws people from all over the country.”

Rogers, however, says help is on the way — and soon. ABCCM, he reports, is working with Homeward Bound, the city and the VA to reach “functional zero” on veteran homelessness by January. “Every veteran in our community and the county — we know who they are, they have a place to be, and they can be housed.” Functional zero means that when people become homeless, there’s a system in place that quickly gets them back into some form of housing.

But for local nonprofits, program funding and the associated administrative costs, notes Alexander, remain constant concerns. “There’s a real disconnect among funders between what they’re willing to fund — usually direct program activities — and what it takes to actually operate the most effective services for this population.”

Last year, for example, “Homeward Bound spent less than 10 percent [of its total budget] on administration,” he says. “Unfortunately, for us to continue innovating and helping as many individuals and families, we must have our administrative capacity grow alongside our program capacity. No one wants to pay for administration, but it’s how we operate the programs that most funders want to invest in.”

What’s next?

Although the 10-year plan may not have accomplished everything it set out to do, its successes and shortcomings alike spotlight what needs to happen next, says Tugman.

“The Homeless Initiative Advisory Committee is developing a five-year strategic plan now that the 10-year Plan to End Homelessness has come to an end,” she reports, adding that the new plan will include “an annual review and benchmarks.” The city, says Tugman, is studying local data and national trends to help it plot the best way forward.

“Some of the large brush strokes we can all agree on,” Rogers explains, “are increasing funds for affordable housing, encouraging developers to set aside some units or as much as they can, and looking at how we really support efforts on multiple levels.”

Increasing the supply of affordable housing has become most of these agencies’ central focus. But with a vacancy rate of less than 1 percent for multifamily rental housing in Buncombe County and the median rent for a one-bedroom apartment over $800, according to the Bowen report, this will require some creative thinking on the part of city and county officials as well as developers.

“At its most basic, homelessness is caused by a lack of [available] housing,” says Cantrell. The Be Loved Community, she explains, “spent a week on the streets in September for our Festival of Shelters to raise awareness about this crisis, and we’re continuing to advocate for creative solutions and new laws and policies.”

Mandatory inclusionary zoning within neighborhoods, Cantrell maintains, could help; she’d also like to see some of the proceeds from the hotel occupancy tax used to fund affordable housing. “We need to make sweeping law and policy changes that will create more affordable housing now and in the near future,” she asserts. Possible approaches, notes Cantrell, include “more funds in the Housing Trust Fund, utilizing land banking to create housing, offering supports to landlords, and flexible zoning laws or nondiscrimination laws that safeguard those who have vouchers.”

Meanwhile, Cantrell and the Be Loved Community are working to establish more places homeless people can go during the day, as well as more transitional housing.

“We also hope to continue to support folks who are on the streets to raise their voices and advocate for the changes they believe are needed to respond to this housing crisis and end homelessness in Asheville.”

If you build it…

Other local organizations are also working to expand their facilities. ABCCM, says Rogers, is focusing its efforts on “the shortage of very low-income affordable housing units” for people “at or below 30 to 50 percent of the median income.”

Using donated land, he explains, “We have a Veterans Village project scheduled for groundbreaking in 90 days” near the nonprofit’s Veterans Restoration Quarters on Tunnel Road. Also in the works is Transformation Village, which will be near Interstate 26 and a bus line.

“Our goal is to create 50 beds for emergency shelter, 50 beds for transitional housing and 200 for permanent, supportive housing,” Rogers says proudly. “The big dream now is to raise $5.5 million to build these larger facilities that will double our capacity.” The nonprofit has about $3.5 million in pledges so far, and in the meantime, the projected rents are expected to cover the financing costs for Veterans Village.

Meanwhile, Homeward Bound is working to expand AHOPE’s role as the first stop on the road to permanent housing. The existing facility, says Alexander, will become “the primary point of entry in the community for coordinated assessment. Much like the emergency room at our local hospital, coordinated assessment ranks these individuals in order of vulnerability, so we permanently house those most at risk first.”

In general, he continues, “We need to make the transition to a permanent housing model of care, rather than a crisis-driven model dependent on temporary housing.”

This, notes Russo, may mean that Homeward Bound’s retention rate takes a hit, but that’s beside the point. “Statistics don’t really matter to us as much as making sure people are safe and sheltered and working toward being housed. That’s our job.”

A fresh start

“Deangelo” is a soft-spoken 27-year-old from Wisconsin. There are several dollar bills pinned to his jacket, which elicits confused queries from some of the other folks at AHOPE. “It’s something we used to do in high school on somebody’s birthday,” Deangelo explains; today is his birthday.

He says he came to Asheville on the advice of a friend in Virginia, where he was stranded after being fired from his job as a sales marketer. “Someone stole my wallet and all of my licenses and cards,” he reports. Deangelo is working with AHOPE staff to get copies of his birth certificate and other documentation; in the meantime, his lack of identification has hampered efforts to find a job here.

“I did some work for a social bar a couple weeks ago,” he reports. “The lady there said she’d try and give me a regular job once I get my paperwork back.”

Deangelo’s situation is typical of the kinds of barriers that stand between the homeless and stability. Partners in the 10-year plan, says Russo, need to provide clients with access to both jobs that pay a living wage and transportation to and from the worksite. “At any given time, between 10 and 15 percent of our homeless clients have a job that’s challenging for them to get to, because of the limitations of public transportation; they frequently spend an hour and a half on either end of their commute, besides a full workday. That’s exhausting to maintain.”

Russo also hopes public perceptions of the homeless will continue to shift. “Most people who are homeless have had a normal life crisis — a job loss, a mental illness, a divorce or a medical illness — but didn’t have the support they needed to stay in housing,” she explains. “That’s why Homeward Bound exists, to give people — our neighbors — the help they need in a time of crisis.”

To that end, says Tugman, “The city of Asheville, the advisory committee and key stakeholders will continue to endeavor to make awareness and discussion of the issues surrounding homelessness … part of the discourse of our community.”

Meanwhile, Deangelo says he’s hoping to stay in the area and eventually find steady employment. “I’d like to start working as soon as I can. I want to get back on my feet and feel independent again.”

One way bus tickets to another city with a signed pledge not to return to AVL without a job is a solution, but local ‘leaders’ will

never consider the obvious…

That’s not really a solution, Mr. Caudle. In fact, it’s part of the reason we have so many homeless people here in the first place. It’s called “Greyhound Therapy.” We get homeless people shipped in from Atlanta, Florida, Charlotte, and the like, while we send ours to Milwaukee and California, among other places.

Bus tickets help snowbirding so they are win win, but pledges would obviously be ignored, as they should be. They also help the intercity bus system reach critical mass.

When I see anecdotes of people moving here from Greenville and Wisconsin looking for opportunity, I cannot help but ask the question “Why Asheville?” This is a small city with very little in the way of employment outside of healthcare (which requires advanced education) and hospitality (which pays minimum wage or less). Could it be that our “progressive” city government has developed a reputation (largely un-earned) as place that shelters the less fortunate and encourages welfare seekers?

That is a good question, Big Al, and one I’ve wondered about myself. I participated in a semester-long Housing Insecurity service project/workshop while studying at Warren Wilson College, where we worked pretty closely with several of the local agencies and the homeless population. From what we gathered during that process, Asheville does indeed seem to have a regional reputation for the quality and extent of services offered to those in need.

In fact, I’ve heard (anecdotally) from several folks living on the street that in the past, other cities in the region have issued homeless people with one-way bus tickets to Asheville in order to pass the buck, essentially. However, I can’t substantiate such claims, so I don’t know how common that practice was or is.

But I think you bring up a very good point: Asheville is a small city that already struggles with job diversity, and is only capable of providing so many resources. I can’t say why so many folks experiencing a housing crisis choose to come here, other than perhaps Asheville is viewed as a friendlier, more accepting place to seek help and support. Being known as a tourist town may also play a factor.

Ultimately, I believe it would be beneficial down the road to increase collaboration among various cities in the Southeast and nationally, so that those in need of assistance and help getting back on their feet don’t have to leave their home to seek support in Asheville or elsewhere.

I believe there are TWO things going on here:

1) Asheville’s “progressive” (but not really) government makes lots of noise about being generous to its’ homeless, which draws more homeless from other places to become “Ashevillians” and take advantage of the (alleged) generosity.

2) Asheville is a tourist town with a very walkable downtown, which means lots of people on foot with expendable income for out-of-town homeless to prey on.

What needs to happen is for city government, local hotels and businesses to advertise to visitors “don’t feed the bears” with cash, and instead offer vouchers to local homeless resources instead. Durham’s Ninth Street district was plagued with panhandlers until they took such measures. When pedestrians stopped giving money without suffering guilt, panhandlers moved on.

As for collaboration with other cities, I doubt they will be interested so long as Asheville continues to hold itself apart as an island of free-wheeling liberalism. In some way, sending their homeless here (if this turns out to be true) would be an effective way for red states to tell a blue city “screw you, cesspool of sin”.

I think Big Al is on target.

Obviously the proper direction for buses to go is South in Autumn and winter, and North in spring and summer. Or otherwise wherever homeless people might be the deciding vote in places that are split 50/50, like Nevada. Or Colorado if they like pot.

Greenville is fascist and Wisconsin is freezing, so the reason is pretty clear to me. Greenville is also sweltering in summer.

Cantrell is dead wrong about zoning. Zoning is the ultimate cause of homelessness as well as loss of construction jobs. Zoning can NEVER be any part of the solution, Cantrell should REPEAL zoning, not heap on more of it. Though her version does force the repeal of some contradictory zoning regs. Cantrell refuses to admit the essential fact that she is trying to REPEAL regulations, thus she loses libertarians out the gate and so is doomed.