For years, there’s been a two-pronged assumption about how public school teachers spend their summers. The first part is that, like their students, educators get multiple months off for vacation.

“That’s pretty accurate,” says Chris Lengle, a kindergarten teacher at Estes Elementary in South Asheville. “Once we leave for the summer, once my classroom’s packed up, I won’t think about school until mid-August when I have kindergarten orientation.”

But what about the other public perception, that this is paid time off?

“No, there’s no paycheck. $0,” adds Lengle, who’s been teaching for 21 years, the past six at Estes. “I’m trying to impress this upon these young teachers: They should be putting money away. That way you don’t have to work.”

One savings plan is the Summer Cash program through State Employees’ Credit Union. The share account is available to public school, university and community college system employees who are paid nine, 10 or 11 months per year. Teachers choose an amount to transfer from each paycheck during the school year to their Summer Cash account, typically by payroll deduction, then the funds are automatically transferred in one or more payments over the summer based on their salary schedule.

However, if no such plan is enacted or there’s no spouse or partner to pay the bills over the summer, teachers have to keep earning money somewhere — and sometimes that’s back in the classroom.

Minds at work

This summer marks the third year that Dawn Lory has taught summer school. The third-grade teacher recently finished her 17th year at Estes and 25th overall as an educator. She gets two weeks off before another five-week run in the classroom. After that, it’s only two weeks before she’s back to planning for the new school year. But she says the schedule isn’t as bad as it may sound.

“Summer school is a lot less stressful because you’re not grading and there are no parent conferences,” Lory says. “You’re still with kids and doing the part you like, but you don’t have to do all that extra stuff that’s so overwhelming — mostly the paperwork, quite honestly. Without all of that, it’s a much easier day, so there’s a bit of rest built into that.”

Other than part-time tutoring, which she continues to offer, Lory didn’t work summers when her children were young, largely because the cost of day care would have offset much of her earnings. But now that they’re in college, she works extra hours to help pay their tuition.

“My daughter started at Appalachian State University three years ago, and college is so expensive now,” Lory says. “I don’t want her to graduate with $80,000 of debt.”

For much of her professional life, Meredith Licht, who’s taught English and social studies courses at Brevard High School since 2001, likewise focused on being a mom while school was out.

“Summers were for my children because most of the school year was for other people’s children,” Licht says. “But our kids are now grown and flown, so I have a little bit more freedom in the summer.”

With that extra independence, however, Licht noticed that she became restless and dissatisfied over the four or five weeks before the new school year began. In hopes of combating those feelings this summer, she plans to work 12 hours per week at Hiker and the Hound, an outdoor clothing and equipment shop in Cedar Mountain.

“It’s going to give me a little bit of a schedule, a little bit of a routine to follow and a little bit of pocket money,” Licht says. “I plan to retire in about four years, and I’m trying to save up for an RV so my husband and I can enjoy our retirement and travel and see all the places and do all the things that we didn’t have the time or money to do when we were younger.”

Before getting married and becoming a father, Lengle kept working during the warm months, often at summer camps. Now, he tutors a few hours a week over the summer and will go to Estes for five “trade days,” spread across the off months. For Lengle, these workdays consist of interviewing teacher candidates; a planning day with his teaching team; another planning day for the Jump Start to Kindergarten orientation; and one Leader in Me day of professional development. As with the Summer Cash program, the “trade days” do his future self a favor.

“You try to get your five days in the summer because you want those five days off throughout the year,” Lengle says. “You can take them only when the kids aren’t there — an optional teacher workday in December is a good example. No one wants to work two days before Christmas, so you usually want to burn that day.”

Rest and recharge

All three teachers agree that higher pay for public school educators would make true summers off more feasible, and they also feel that year-round school — with multiweek breaks every few months — could lead to more well-rested teachers.

“Every educator I’ve ever spoken to who works in a year-round setting says once you do it, you never want to go back,” Licht says. “It provides the time that everybody needs — not just the educators, but the students. They need a break from each other, not only just to be kids, but also to let the content and the skills that they learned percolate.”

Instead, summers remain the primary time off for teachers in Buncombe and Transylvania County Schools to do what they need to rest and regroup before the following school year — which Lory feels is especially important for educators just getting into a challenging but rewarding profession that she, Licht and Lengle consider a calling.

“The younger teachers, they’re working themselves to death during school year. It’s a hard job,” Lory says. “Some of the veteran teachers, we have the materials, we have the knowledge, we’ve taught the lessons. We don’t spend countless hours trying to learn the curriculum in our evenings. But the people that do have to use that kind of time, they’re fried.”

Even with years of teaching to build on, experienced educators like Licht have valued their time away from the classroom to a greater degree since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. In addition to the amplified pressures heaped on teens via social media and the political, economic and environmental uncertainties of the world they’re about to enter, she notes that the interruptions of a traditional classroom experience over the past three years have taken their toll on students and teachers alike.

“It’s incredibly difficult, and it takes a lot of emotional energy and a lot of psychic energy on top of the physical energy of managing a class and doing all the things that come with teaching,” Licht says. “So, it’s been incredibly draining these last few years. And if I didn’t have these summers, I don’t think I could return to the classroom.”

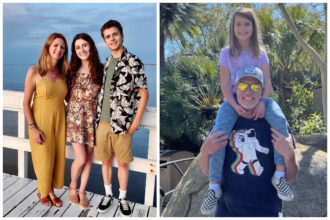

Last summer, Licht and her husband, Josh Tinsley, a fellow educator who teaches English and serves as the yearbook advisor at BHS, got a rescue dog and spent much of their summer walking the pup on trails and going camping. She refers to being away from other people and technology as “the ultimate reset” and “incredibly necessary” — sentiments that resonate with the similarly outdoor-minded Lengle, whose wife, Katy Lengle, is a second-grade teacher at IC Imagine Public Charter School.

The Lengles’ daughter, Annie, recently turned 8, and together they take what Chris calls “a big grandiose road trip” each July that always brings them through Eau Claire, Wis., to visit with his in-laws. Later in the summer, Chris and Annie will continue their tradition of taking a daddy-daughter trip.

“After doing this for a while, I’ve figured out the best way to navigate the system and just taking some time for myself over the summer and spending it with the family,” says Lengle, who also works on house projects during his months off. “Last summer was the best summer. My daughter is 8, so I’m just trying to just embrace all the time I have with her before she goes off to college. We just spent the whole summer together, and hopefully, we have another summer like that this summer. That’s what I want to do every summer until I retire.”

Teachers who complain about low salaries always neglect to mention that they are effectively getting paid full time wages for only working about 8.5 months a year, given all the breaks. Xmas, spring break, Thanksgiving, federal holidays… makes their hourly pay much higher than they claim. The school days are laughably short now, so even if they stay until 5 doing prep, they are still not working more than 40 hours a week for maybe 37 weeks in a calendar year. Taxpayers need to keep this in mind, because teacher unions sure don’t want you thinking about it.