Asheville may be a top dream destination for many folks, but for an increasing number of newcomers and old-timers alike, the No. 1 dream destination may be just down the road a ways.

With the challenges of urbanization besetting Asheville, newcomers and locals alike are turning to surrounding towns and communities in search of cheaper housing and a less urban representation of the mountain experience.

“For some people, [Asheville] is much bigger than what they expected and a little more eclectic than what they thought,” says Beth Carden, executive director of the Henderson County Tourism Development Authority. “People might not have realized, but they’re looking for more of a small-town mountain experience. That’s what we have to offer.”

But like the city, many of these small towns and communities are grappling with the challenges of maintaining their identities while encouraging smart growth, even as they seek to ensure that their contributions to the region aren’t eclipsed by Asheville’s popularity.

Take me home, country roads

“Small towns … offer the authenticity that make them unique and a real draw for tourists,” says Steve Morse, a professor at Western Carolina University who studies tourism development. “Tourists spend money in small towns and rural areas that reflect the area’s authenticity in culture, history, music, arts and crafts, and food.”

Carol Groben, who moved to Swannanoa in 1999, says she was drawn by the beauty of the area, the access to outdoor activities, a friendly atmosphere and the ability to be close to Asheville while still living in a rural community. “One of the things we love best about Swannanoa is that, despite its proximity to Asheville, it has its own very distinct identity and character,” she says.

White Horse Black Mountain owner and WNC native Bob Hinkle moved to Black Mountain in 2007 after several decades of living in New York City. Since then, he says he’s noticed an influx of people seeking an arts-focused culture without the hustle and bustle of Asheville. “You hear these stories of people trying to go to the Asheville Symphony and spending 45 minutes trying to park,” he says. In Black Mountain, by contrast, “parking is free, and it’s abundant. Stuff like that is helpful.”

The small-town vibe is a central marketing tool for places like Hendersonville, according to Carden, who proudly points out that Henderson County recently ranked 15th in the state for tourist draw. “It’s a feeling people get,” she notes. “People even speaking to you on the street is becoming a rarity in America, and you still get that here.”

Growth by numbers

The communities that comprise the Asheville metropolitan area have all experienced growth to varying degrees, according to census data from 2004-14. North of the city, growth has surged in places like Weaverville (31 percent) and Woodfin (11 percent). In Black Mountain, a few miles east of the city, the tide has been slower, at 6.9 percent.

To the south, Arden has grown by about 20 percent in the past year alone, according to Jonathan Jones, owner of the Welcomemat Services Asheville franchise, which helps local businesses connect with new residents.

While retirees and families make up a big portion of small-town population growth, a surprising number of transplants are millennials, Jones says. “The midmarkets [like the Asheville area] are incubators for [younger] entrepreneurs, where they can try out new things and really start their business, and still provide the urban accommodations they need.”

Outside Buncombe, growth correlates roughly to transportation infrastructure. Hendersonville, a relatively short drive down Interstate 26 from Asheville, saw its population grow nearly 18 percent between 2004 and 2014, while Mars Hill, north of the city on I-26, grew by 25 percent in the same time frame.

Farther from the interstates, growth has been slower. Marshall’s population, for example, grew by only 6 percent during that time, while Burnsville grew by only 4 percent.

New kids on the block

While the raw data may not show a vast change in population in all of these places, numbers don’t always tell the whole story. Oftentimes, the types of people coming into a small community can impact its character.

The neighborly vibe of Weaverville lured Matt Danford, a semiretired transplant from Washington, D.C., to open Blue Mountain Pizza and Brew Pub there in 2004. “I wanted to have a restaurant that would become a kind of hangout place,” he recalls. “I looked in Canton [and] downtown Asheville, but I couldn’t find everything I wanted. So I went out to Weaverville, and it was love at first sight.”

Danford says he’s witnessed the rebirth of Weaverville’s Main Street in his time there. “People used to think Weaverville was just a place off the highway,” he notes. “Now, it’s a real artsy place, where people can come and spend an afternoon, have something to eat, walk around. The town has really grown up around us.”

But a flood of new faces has its drawbacks: In Fairview, retirees and affluent newcomers have driven up the cost of living and subsequently driven younger people out, says Adam Reeck, a graduate student at North Dakota State University who wrote a study on community assets in Fairview while living there over the past year.

“There’s two ways that a population can get older: if older people are moving in, or if younger people are moving out,” he notes. “Based on the demographics, it’s a combination of both happening in Fairview.”

This flux has also caused some tension within the community, says longtime Fairview resident and N.C. District 115 Rep. John Ager. “The growth of Asheville has put development pressures on Fairview, and there is a certain distrust between newcomers and the older families.”

To some degree, these tensions are inevitable, Morse notes. “Growth always changes things. For some it’s positive, for others it’s negative.”

Keeping up Main Street

The growing number of new residents in these outlying areas offers opportunities for both established businesses to expand their consumer base as well as economic development officials seeking to attract new industries to the area.

“The value of the new families moving in is they’re nobody’s customer yet,” Jones says. “It’s the perfect time [for businesses] to build a relationship with that new family because they’re out of place like no other time in their lives.”

David Gantt, chairman of the Buncombe County Board of Commissioners, confirms that “much of Buncombe’s recent job growth has been outside the city of Asheville in more rural areas of our county,” adding that Buncombe officials work regularly with local representatives from these areas and regional groups like the Land of Sky Council to help promote these communities to potential new businesses.

But where people tend to congregate, big retail chains usually aren’t far behind. “I found it interesting that people moved to [WNC], and as soon as they got here, wanted to make it like the place they left,” says Danford. “It didn’t matter that there was already a good local hardware store; they wanted the big-box store.”

In response, many towns have taken proactive steps to preserve the character of their downtown areas. “I don’t always agree with the town fathers, but they have made a great decision to limit chain retailers to outside the ‘village’ of Black Mountain,” Hinkle notes. “As long as that remains in place, [downtown] Black Mountain will remain the kind of picturesque place it is.”

For communities without established economic centers, however, keeping residents’ dollars in town can be difficult. “When you look at the data for employment, your average business in Fairview is really small,” Reeck notes. “You can also find data that your average Fairview resident drives over 18 or 20 miles to work. They’re making money in an outside area, but a lot of it is [also] being spent outside of the community.”

Running out of room

Many smaller towns, similar Asheville itself, are hampered in their efforts to accommodate the legions of new residents knocking to get in by the limited amount of available developable land in the mountains.

“[Between] the six conference centers, the two colleges, downtown, the river, the interstate — you’ve got a limited amount of land that can be developed,” says Bob McMurray, executive director of the Black Mountain/Swannanoa Chamber of Commerce. “Right now, rentals are as scarce as I’ve ever seen them.”

With developable land at a premium, the threat to open spaces and farmland has become more pronounced, despite the efforts of local farmland preservation officials and private land trusts to implement conservation easements. (See “Saving WNC’s Farms,” Nov. 27, 2015, Xpress)

Between 2002 and 2012, Buncombe County’s farm acreage shrank by 25 percent, from 94,934 total acres to 71,480 acres, while the total number of farms dropped from 1,192 to 1,060, according to statistics from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Meanwhile, Madison County’s total number of farms decreased 26 percent, while similar declines occurred in Haywood (25 percent) and Henderson (11 percent) counties.

This phenomenon has been on display all too clearly in Fairview, says Reeck. “With the price of land going up and the [increasing] number of people that want to get into Fairview, there’s a lot of pressure for people who do own large tracts of land to split it up and sell it off to a developer.”

Traffic woes

Traffic infrastructure has also become an issue for WNC’s small towns, many of which lack consistent access to public transportation. As more outlying areas become bedroom communities for commuters working in Asheville, everyone winds up grappling with increasing congestion along main arteries to and from the city.

Danford recalls that when Blue Mountain opened in Weaverville, “You could sit [in the middle of] Main Street and talk to people. Now you have a hard time crossing Main Street, there’s so much traffic.”

Efforts to address infrastructure deficiencies can have adverse side effects for a community, such as road closures and long-term construction projects. “Infrastructure is the biggest challenge for local business owners,” Jones acknowledges. “Long-term construction can [alter] traffic patterns and really impact certain businesses. Infrastructure often becomes the last thing cities look at, when it needs to be the first.”

Despite the technical difficulties, improving local infrastructure remains a priority for small towns. Black Mountain officials are advocating for a new interchange between I-40 and Blue Ridge Road to reduce traffic in the downtown area in the coming years, says McMurray. “If we can get that interchange, it’ll be a big plus for Black Mountain.”

In Brevard, town leaders are also beginning to look at parking expansion downtown, according to Stephen “Billy” Harris, a real estate broker in the area for 13 years, as well as updating the unified development ordinances and code changes to address the commercial growth in the corridors leading to and from the downtown area.

“With Oskar Blues and new industry coming to town, it has put light on current and future infrastructure needs,” he says. While no specific direction has been taken yet, Harris says that local and county officials are working with businesses to identify potential infrastructure needs for the future.

An issue of incorporation

Unincorporated communities — populated areas that lack an official municipal structure, leadership or boundaries — face an especially complex situation when deciding how best to manage growth and maintain their distinct charms. With no local administrative body to lobby county and state government for their needs, determining what direction to take in response to growth issues can be a challenge.

“One of the things that all Fairview residents seem to be fairly united upon is that they want to keep Asheville out,” says Reeck. Local debates over zoning changes and incorporation throughout the 1980s and ’90s “pretty much divided the community,” according to Reeck, with popular sentiment ultimately coming down against incorporation.

Similarly, a referendum in Swannanoa on incorporation in 2009 was soundly defeated by residents, who cited increased taxes and fears about future annexation by Asheville. And Barnardsville, once an incorporated community, took the unusual step of unincorporating in the mid-1970s, according to Bob Bowles, a resident of Barnardsville for 25 years and former director of the Big Ivy Community Center.

“At that point in time, the federal government was providing more money for unincorporated areas than incorporated areas,” he says. “In order to get some of the things done that the town leaders thought they should have, they disbanded themselves.”

Remaining unincorporated, however, can make upgrades to infrastructure harder to push through. Barnardsville has struggled with a lack of high-speed internet access, Bowles says, as well as calls to discontinue its post office branch and concerns over being lumped together in voting districts with other communities it has little cultural connection to.

“Who do we turn to when we need to talk about having a new medical center or how we get improved access to economic opportunities?” he asks.

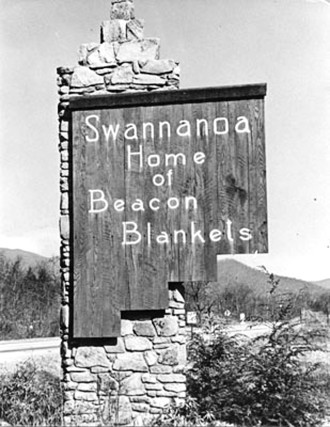

In Swannanoa, the closure of the Beacon blanket factory — once the largest blanket manufacturing site in the world and the focal point of the community — in 2003 created an identity crisis that the community is still seeking to recover from, says Groben.

“It would be wonderful to see a revitalization of this historic downtown area,” she notes, “as well as positive development on the now-vacant 40-plus acres that once were home to Beacon Manufacturing.”

Town and the city

While each town and community surrounding Asheville maintains a distinct character and heritage all its own, their proximity to the city undeniably remains vital to their prosperity.

Less developed communities often rely on the city for access to amenities and employment. “The exodus I see going out of Barnardsville every day into Asheville is phenomenal,” Bowles observes. “[Residents] work in the universities there, in the medical centers, and the farmers market is there. I don’t think the community could survive without that relationship.”

What’s more, Asheville’s marketing prowess benefits the entire region by attracting tourists to the area. “Some in economic development see tourism [to] Asheville as ‘the first kiss’ of a long relationship in getting visitors to become business investors in surrounding areas,” Morse says. “Tourists, like entrepreneurs, usually don’t know and don’t care where city and county lines are; they see the area as a region.”

Despite the symbiotic relationships among WNC communities, Carden admits it’d be nice to be recognized more often for the contributions her community brings to the table. Asheville often gets credit for Sierra Nevada being in WNC, but it’s in Henderson County, by Sierra Nevada’s choice, she notes. “It’s hard to build a brand destination when they don’t give you credit sometimes for being who you are.”

Similarly, McMurray says that while Black Mountain relies on Asheville and Buncombe County for tourism marketing, the town has a strong reputation on its own merit. “We think between the conference centers, the camps and the tourists, there’s over half a million people a year coming through the area,” he notes. “We’re our own destination.”

Looking toward the future

With folks continuing to flock to the mountains for business, pleasure or to start a new phase of their life, it’s reasonable to expect that more and more residents will seek outlying communities as an alternative to Asheville in the near future.

“While Asheville has become a nationally recognized, iconic destination, we will not have the affordable or workforce housing to support all the people who wish to relocate here,” Gantt predicts. “Many folks will move to communities that are more affordable or that provide less urban settings than we do.”

The geography of the mountains limits the city’s options for expansion and encourages movement to the surrounding towns, says Jones. “You can’t have the urban sprawl that a place like Phoenix might have. You have to go north and south to Arden, Fletcher, Hendersonville, Weaverville and Burnsville along those corridors.”

As advanced technology makes it easier for folks to work remotely, Morse believes the next generation of WNC entrepreneurs and business owners will increasingly choose to settle outside urban centers. “With fast and reliable broadband connections like we have in WNC, this next generation of creative class of workers will be choosing smaller towns with a high quality of life,” he says.

Regardless of the direction and pattern that future growth takes, Gantt says it’s important that the city and the surrounding communities work together to ensure a mutually beneficial relationship for the entire region. “Good planning, partnerships with developers of workforce housing and coordination of financial resources between local governments will be an essential part of the solution.”

In many ways, WNC is more the sum of its parts than a collection of separate municipalities, says Carden. “It’s like a big quilt. We all make the experience much better when we work together.”

> Asheville maintains a distinct character and heritage all its own

“Can you spare me seven cents?”

Interesting and well written article.

Could I suggest the word ‘gentrification’ be used instead of the word ‘urbanization’ in this context for

future articles as being more accurate?

The G word is what is hurting WNC in general, economically as well as in soul sucking icky-ness.

The U word implies stereotypical cross eyed, buck toothed denizens of the cartoon ‘Snuffy Smith’ with their fear of indoor plumbing, electricity post- New Deal and clinging to oversize checkers at a Cracker Barrel restaurant. Just saying.

Hendersonville, Waynesville, Barnardsville, Burnsville, Weaverville, Mars Hill, etc are all thinking

“Oh no, how long do we have until Haywood Rd. (from West Asheville) reaches us?”

Don’t worry, The Mtn X will gladly proclaim it.

Thanks for the thoughts, Boatrocker. You made a good point about “gentrification” vs. “urbanization”. Definitely will take it into consideration for future reference. Nice Snuffy Smith reference too.

Rex Morgan, MD’s quiet contemplation and Cathy’s “Ack!” just don’t communicate the intricate meaning like Snuffy does. Believe me, I’ve tried and failed in other contexts. If Spiderman were carried by any local papers at least I could use “With great power comes great responsibility”.

If any small town could USE some gentrification, it is Marshall. Such a pretty location, but it still looks like an all-but-abandoned ghost town.