Lines around the block, screaming fans, scalpers hawking questionable tickets from the sidewalk — Climate Change and Asheville’s Urban Forest, a symposium organized by Asheville GreenWorks for Thursday, Nov. 14, 5-7:30 p.m., bears none of those markers of a sold-out show. Nevertheless, the event had to be moved earlier this month from The Collider to A-B Tech’s Ferguson Auditorium after accumulating a 150-person waitlist.

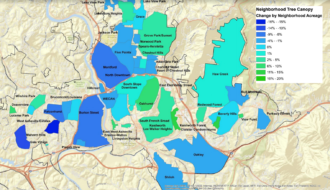

That level of public interest, says Steve Rasmussen of the volunteer Tree Protection Task Force, reflects a rising sense of urgency around the fate of the city’s wooded areas. The Urban Tree Canopy Study prepared for Asheville city government, which was published in October and will be discussed publicly for the first time at the symposium, found that the city lost 6.4% of its tree cover, or 891 acres, between 2008 and 2018.

The most drastic loss has occurred in Rasmussen’s own neighborhood, West Asheville Estates, where infill development has eliminated nearly 33% of tree cover over the past decade. He says that statistic matches up with the “constant, god-awful sound of chainsaws,” increased stormwater runoff and the hotter streets he’s recently experienced in his neighborhood.

“Everybody has a story about the tree down the block, the 100-year oak that just got cut down or the forest they used to love to walk around in that’s gotten wiped out,” Rasmussen says. “Well, now we see that it’s not just you and your story: It’s your whole city.”

In June, Asheville’s tree advocates suffered a setback as the city chose not to fund roughly $354,000 in requests for urban forest protection, including $250,000 for an urban forest master plan and over $104,000 to hire and outfit an urban forester. Now, a broad coalition of organizations — nine nonprofits, Lenoir-Rhyne University and UNC Asheville’s National Environmental Modeling and Analysis Center — is rallying around the canopy study results to again request city action, emphasizing that trees are critical to help Asheville avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

Seeking shelter

The symposium will see the debut of two new campaigns spearheaded by the Tree Protection Task Force: Cool Green Asheville and the Asheville Climate Action Initiative. In the words of Stephen Hendricks, chair of the city’s Tree Commission, both efforts seek to “connect all those dots” between urban forest cover and climate resilience. “It’s not just a tree-hugging issue. It’s a conservation and climate issue; it’s a public health issue,” he says.

As cities develop, Hendricks explains, they often replace vegetation with concrete infrastructure and buildings, impervious surfaces that lead to stormwater and pollutant runoff. Developed areas can also act as heat sinks and cause urban settings to be hotter than their surroundings; Asheville’s government expects both extreme rainfall events and heat waves to become more common as the climate continues to change.

“As we get higher temperatures, particularly in the summer, [a heat island] essentially multiplies the effect of climate change,” Hendricks notes. Even if the region as a whole experiences only a 1.5 degree Celsius (2.7 degree Fahrenheit) increase in temperatures, the most optimistic target for global warming set by the international Paris climate agreement, he says, Asheville’s core could see a heat bump of four times as much or more.

Beyond the public health effects of higher urban temperatures, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has said can lead to increased death rates and hospital admissions, Hendricks suggests Asheville’s lucrative tourism economy could suffer from unchecked climate change. “Imagine if we were a city 10 or 20 degrees [Fahrenheit] hotter. How many people would be coming here in the summer?” he asks.

Hendricks argues that because greenhouse gas emissions, the major cause of human-driven climate change, can’t be reduced or eliminated entirely through local action, the city should focus on trees and other green infrastructure to better buffer itself. “We can do our part, but emissions are global,” he says. “We can mitigate locally with some green solutions that will put us in a much more resilient situation.”

Among the nonprofit groups backing this approach is the Elisha Mitchell Audubon Society, led by Nancy Casey. She says that a recent National Audubon Society study found that two-thirds of North American bird species could go extinct due to climate change — and she suggests that birds are a bellwether for the health of human societies.

“Anything we can do to preserve and increase urban forest cover, both for bird habitat and carbon uptake, will help,” Casey says. “We believe the fate of birds is inextricably linked with our own.”

‘Stop the bleeding’

Action is already underway, Hendricks notes, through Asheville city government’s reevaluation of ordinances with an eye to tree protection. He says that the process will “stop the bleeding” of continued canopy loss by fixing the biggest legal loopholes; advocates expect the changes to go before City Council sometime in the spring.

Although Chapter 20 in the city’s Code of Ordinances is devoted to trees, most of the changes under consideration are targeted at the Unified Development Ordinance in Chapter 7. Ben Woody, Asheville’s development services director, explains that the shift in focus responds to land development as the most pressing urban forest threat.

“The city is currently working with the Tree Commission and Development Customer Advisory Group to implement several goals of the [Living Asheville] Comprehensive Plan by introducing a requirement that private land development projects of a certain size be required to preserve some of the existing tree canopy on site,” Woody says. “These amendments will likely fall into Chapter 7 (the UDO) rather than Chapter 20 as they apply to private land development.”

Asheville has had the power to make such changes since 1985 thanks to the efforts of former state Reps. Marie Colton and Martin Nesbitt, who added Asheville to a state law that also authorized the city of Raleigh to regulate certain trees on private property. The city’s first tree ordinance was passed in 1986, but its language has not been revised since 1997.

That language, as Xpress has previously reported (See “Branching out,” March 3), lists the establishment of a master street tree plan — which Asheville interprets to be the same as the urban forest master plan — as the responsibility of the city’s Parks and Recreation Department. However, according to Chad Bandy, streets manager for the Public Works Department, all city tree crews are currently under his department; parks and recreation hasn’t had any employees responsible for tree issues for at least five years.

Canopy contrasts

Cindi Sullivan, the executive director and president of TreesLouisville and the keynote speaker at the upcoming symposium, says the proposed ordinance changes are a good start. Her organization has promoted similar development ordinance updates in the large Kentucky city, and in 2017, Louisville added both a metro tree ordinance and a Division of Urban Forestry to oversee its enforcement.

Yet Sullivan stresses that those moves are only a start. “We both are facing alarming losses of tree canopy and we both are decades behind many other U.S. cities that have been paying attention and have been working on tree canopy preservation and enhancement for years and years already,” she says of Asheville and Louisville.

Asheville’s press release announcing the canopy study results took a decidedly rosier tone. According to city spokesperson Polly McDaniel, Asheville compares “favorably” to other cities in terms of canopy, with its total coverage of 44.5% in the range of seven other municipalities including Charlotte (47%), Cookeville, Tenn. (40%), and Pittsburgh (40%).

However, the study only compared point-in-time canopy measurements, not losses over time, and the cities being compared differ in population size by over an order of magnitude, from approximately 34,000 for Cookeville to more than 872,000 for Charlotte. (Asheville’s city population is roughly 92,000.) When Xpress asked Bandy if Asheville had weighed its rate of canopy loss against that of other cities, he said that direct comparison was not part of the scope of the study and that he did not have those numbers.

Another chance

As a next step, Hendricks and other tree advocates are again asking the city to fund an urban forest master plan and hire an urban forester. He says the latter request is particularly important in light of the ordinance changes already in the pipeline: “To have a program comparable to other cities, you need a person to coordinate the program, train inspectors, go to development sites and get things worked out before you get to a point where the design’s already done and you can’t make any changes,” he explains.

Bandy confirms that city staff will request funding for the urban forest initiatives in the budget for the next fiscal year. He says the Tree Commission has been in regular conversation with upper-level staff, including City Manager Debra Campbell, and City Council members, but that no firm commitments have been made.

“I do think that management recognizes the importance of the urban forest plan,” Bandy says. “At this point, I think they are having to weigh everything, not just this as a need and a desire, but all of the capital needs and other needs within the city.”

For Hendricks, the need weighs ever more heavily on Asheville, which he estimates continues to suffer a 1% yearly loss of tree canopy. Even as other cities such as Charlotte have stopped or even reversed their canopy reductions, he says, Asheville maintains a steady rate of decline.

“It’s going to keep going down unless we take some action to push it the other way,” Hendricks says. “The longer you wait, the more problems you’re going to have.”

WHAT: Climate Change and Asheville’s Urban Forest

WHERE: Ferguson Auditorium at A-B Tech, 340 Victoria Road

WHEN: Thursday, Nov. 14, 5-7:30 p.m. Free; registration required at avl.mx/6oy

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.