In honor of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, we bring you our regularly scheduled Tuesday History post, one day early.

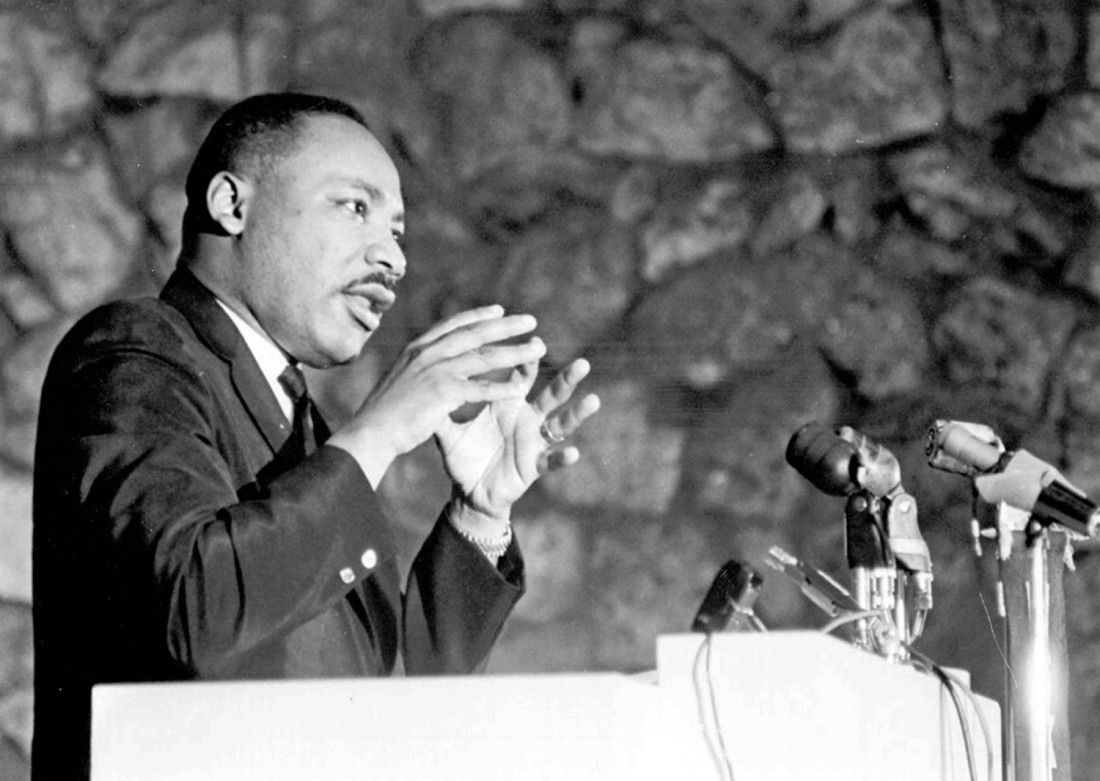

On Aug. 21, 1965, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. addressed an audience of nearly 3,000 people in Montreat Conference Center’s Anderson Auditorium. King, the keynote speaker for the Presbyterian Church’s annual Christian Action Conference, had originally been scheduled to open the three-day event on the previous Thursday. But a massive riot in Los Angeles’ Watts neighborhood — which left 34 dead, over 1,000 injured and close to 4,000 arrested — had delayed his arrival here.

There was controversy before the conference even started. An Aug. 6 Asheville Citizen headline read, “King’s Montreat Talk Already Stirs Unrest.” The article went on to note opposition within the congregation to King’s invitation, which the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church had attempted to rescind earlier that year.

On the day of King’s arrival, the Citizen quoted Buncombe County Sheriff Harry P. Clay, who acknowledged the potential presence of “certain outside violent hate groups.” The sheriff went on to say, “It is my intent that this county remain peaceful and law-abiding. Recent happenings such as those in California, Chicago and Massachusetts will not occur in Buncombe County.” And in fact, there were no major disruptions.

King’s speech, titled “The Church on the Frontier of Racial Tension,” lasted nearly an hour. He outlined a series of issues surrounding the civil rights movement, including social and economic inequalities, the immorality of segregation and the power of nonviolence. His primary focus, though, was the church and its duty to serve everyone.

Over the next four weeks, we will examine portions of King’s speech as part of our Tuesday History series. King was introduced by two individuals identified only as Dr. Calhoun and Mr. Johnson. In his opening remarks, King thanks both men, before noting his delay:

As you know, I was to be here on Thursday evening and, unfortunately, one of the most violent conflicts of our nation, ever in the history of our nation, developed in Los Angeles. And as one who has consistently followed a method and a philosophy of nonviolence, I felt it was absolutely necessary to respond to the invitation that came to me from the Negro leaders of that community to come and offer whatever counsel and advice that I could. And it so happened that I had to be there a little longer than I thought I would. … But I’m happy that you gave me the privilege to come here today. And that’s through sympathetic understanding. You realized why it was not possible for me to be here Thursday evening.

I am certainly indebted to Mr. Johnson for these very kind and gracious words of introduction. As I listen to him with his wonderful and eloquent words of introduction, I felt something like the old maid who had never been married and one day she went to work and the lady for whom she worked said, ‘Anne, I hear you’re getting married.’ She said, ‘No, I’m not getting married, but thank God for the rumor.’

Now, I know all of these wonderful things he said about me can’t be true, but thank God for the rumor.

These are difficult days in which we live. At points, we do live in days of emotional tension, when the problems of our nation and the problems of our world are gigantic in extent and chaotic in detail. And as I stand before you who are so involved in Christian action in the great Southern Presbyterian Church, I would like to use as a subject from which to speak, “The Church on the Frontier of Racial Tension.”

There can be no gainsaying from the fact that we find ourselves in a crisis-packed day. There can be no gainsaying of the fact that we have a crisis in race relations in our country. Some years ago, a great sociologist at Harvard University, Dr. Sorokin, wrote a book entitled The Crisis of our Age, and the thesis of that book was that a crisis develops in society when an old idea exhausts itself and society seeks to reorientate itself around the new idea.

Now this is certainly true in our situation. It is true in our nation at the present time. The old idea of segregation, the old idea of paternalistic relationships between the races has exhausted itself. And American society is seeking to reorientate itself around the new idea of integration, the new idea of genuine, person-to-person relation. This accounts for the crisis of our age and this accounts for the crisis in race relations today.

Whenever a crisis emerges in society, the church has a specific and a great responsibility. It has a real responsibility in the midst of this crisis because the problems involved are essentially moral issues. The church, being the moral guardian of the community, cannot overlook its moral responsibility at this hour.

Now, we must admit that all too often the church has been lax at this point. All too often in the midst of social evil, too many Christians have somehow stood still, only to mouth pious irrelevancies and sanctimonious trivialities. All too often in the midst of racial injustice, too many Christians have remained silent behind the safe security of stained glass windows. But when the church is true to its nature, when it is true to the Gospel of Jesus Christ, and when it is relevant, it is always active in immaterial social change, seeking to guide and direct, seeking to bring the eternal variable of the gossips to bear on the particular situation. This is the great challenge facing the church today. This is the great challenge facing every Christian in these days of racial tension.

Next week, we will continue with King’s speech.

This is amazing. WOW!! Thank-you for this.