Despite lying less than a half-mile from a contamination source that’s been under investigation since the 1990s, the Bradley family’s drinking well had never been tested when David Bradley noticed some folks drilling across the street from his South Asheville home on a mid-August day this year.

Bradley crossed Chapel Hill Church Road to chat, recalls his daughter-in-law, Jenny Bradley. The work crew turned out to be collecting groundwater samples for an ongoing state and federal evaluation of chemical contamination spreading from a 57-acre site on Mills Gap Road, where CTS of Asheville manufactured electrical components from the mid-1950s until about 1986 (see “Fail Safe?” July 11, 2007, Xpress). In the years since, 47 acres were sold to a private developer who built Southside Village, and about nine acres, which are owned by Mills Gap Road Associates, remain vacant.

One of the toxins used by the Elkhart, Ind.-based company and found in nearby private water sources is trichloroethylene, a suspected carcinogen linked to a host of serious health problems, including kidney and lung damage. TCE is one of the contaminants determined to have been in drinking water at Camp LeJeune during the same three-decade period. High rates of various kinds of cancer, birth defects and miscarriages have been found among the people who drank the water there, and former residents have filed billions of dollars in claims with the government.

In Asheville, several families that have relied on drinking water from streams or wells near the CTS site have reported unusually high occurrences of cancer and other illnesses, but a North Carolina Central Cancer Registry report released in 2008 found no cancer clusters there. State health assessors, however, deemed that study “very limited,” and a more comprehensive Environmental Protection Agency review is pending.

The Bradleys had been drinking from two local wells for many decades. David Bradley’s mother lives at the end of Chapel Hill Church Road and has her own well. And across from the church near Pinners Cove, various family members — including David, his partner and her 10-year-old grandson, as well as Jenny and her husband — live in two houses and share a well.

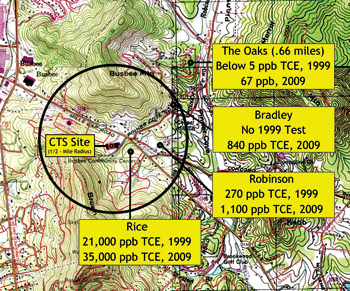

So on that August day, David Bradley asked the crew to sample his family’s 500-feet-deep well. They did, and the results indicated 840 parts per billion of TCE —168 times greater than the 5 ppb that the EPA has set as the maximum allowed for drinking water.

On this occasion the findings prompted a rapid response: The EPA released a Sept. 1 statement announcing the results and calling for all residents who lived within one mile of the old plant and who wanted their wells tested to contact them. Employees of the EPA and the N.C. Department of the Environment and Natural Resources have been “fanning out in our community to map out all the private wells,” says Tate McQueen, one of several local residents who have been critical of federal and state officials’ handling of the CTS contamination. It’s been 20 years since exceedingly high TCE levels were found in the drinking-water supplies of several families that live less than a mile from the plant, he says, arguing that the EPA and the North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources should have identified and tested the Bradleys long ago.

Inexplicably, although a 2001 EPA review described the contamination as an imminent hazard that was likely to migrate downhill and downstream, a state report submitted about the same time omitted the family’s wells and counted just nine private water sources within about a half-mile radius around CTS. Located about 0.4 miles from CTS, the Bradley property lies between the old plant and The Oaks, where a multi-home well tested at 57 ppb in 2007. According to the Sept. 1 EPA release, the Bradley family had “declined … previous offers to sample the well.”

Not true, says Jenny Bradley, who is a nurse. When her husband was about 15 years old, he saw a woman examining the family well. The woman never identified herself, and the young Bradley reported the incident to his father, who called city officials but got no answers. “If that woman was [from] the EPA, why she didn’t talk to my father-in-law?” Ms. Bradley asks. Her family is shocked by the recent findings, she says.

They’ve been told to open their windows because the vapors can cause serious headaches even in limited exposure. Bottled water has been provided while they wait to be connected to Asheville’s water system at CTS’ expense. Meanwhile, the Bradleys must let their washed clothes dry completely before wearing them, and they’ve been instructed to limit hot showers because the warmed vapors are particularly hazardous.

“We’re hoping that this contamination has happened recently, and that we haven’t been drinking it all these years,” says Ms. Bradley, who reports no serious health problems in the family. But she’s worried. Less than a quarter-mile away, the spring water once used by Becky Robinson‘s family tested at 270 ppb in 1999 but at 929 in late 2007. And across Mills Gap Road, on Dot Rice‘s property directly below CTS, TCE levels registered at 21,000 ppb in a spring in 1999, and at 35,000 in a nearby monitoring well earlier this year.

The Rices and Robinsons’ private water sources were capped soon after the 1999 tests, and both families have been on public water ever since. The Oaks switched to public water in late 2007. Earlier this year, CTS initiated a pilot project that extracts noxious vapors from a stream on the Rice’s property. A similar system installed close to the plant in 2006 has extracted about 6,000 pounds of TCE. EPA officials indicate they’re attempting to get the site placed on the National Priority List — the first step toward getting federal Superfund money for a cleanup.

Previous evaluations have failed to qualify the site for NPL status, in part, claim residents McQueen and Barry Durand, because the evaluation process has dragged on for more than two decades. Doug Odgen contacted local, state and federal officials about possible contamination from the site as early as 1990, says Durand. Yet it wasn’t until 1999 that the EPA sent an emergency-response team to the site, where it found TCE levels of 830,000 ppb in the soil underneath a building located on a nine-acre parcel that’s now fenced off. Two years later, EPA investigators warned, “Hazardous substances found in the soil beneath the former electroplating plant are migrating through the subsurface, contaminating groundwater, and being released to surface water at nearby springs. Although … no longer used as potable water, other springs and wells may be threatened unless actions are taken to mitigate the source.”

The author of that report was James Webster, who coordinated the investigation on-site 10 years ago but is now chief of the EPA’s Removal and Oil program, part of the Superfund division, Durand mentions. At the time, Webster recommended such solutions as removing the contaminated soil, says Durand. And then-Section Chief Don Rigger called the contamination levels “some of the highest [he had] ever seen,” according to an Aug. 25, 1999, article in the Asheville Citizen-Times that Durand has on file.

Rigger now heads the Superfund Remedial and Site Evaluation Branch, and Durand is hoping he’ll follow through on clean-up promises. “The EPA is focused on addressing concerns, not the underlying problem,” says Durand. “What’s needed here is action.”

If you live within one mile of the CTS facility and have a private well you would like tested, contact the EPA at (800) 241-1754.

Send your environmental news to mvwilliams@mountainx.com or call 251-1333, ext. 152.

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.