Walk any downtown Asheville street and you’re likely to encounter some quirky storefronts offering unusual products. Together, these “specialty shops” or boutiques, most of them locally owned businesses, are a key component of the city’s distinctive flavor, attracting thousands of tourists each year and helping fuel the economy.

But as Asheville’s national profile rises and more large-scale retail outlets look to stake a claim here, small businesses are taking steps to ensure that this city doesn’t become a victim of its own success.

Sum of its parts

Just how important are boutiques and small businesses in general to Asheville’s economy? In 2013, “retail trade” trailed only “health care” in the number of people employed in the Asheville metropolitan statistical area, according to a U.S. Census Bureau business report. “Accommodations and food service,” meanwhile, was the fifth most common category and employed the third-most residents.

Overall, 98 percent of businesses in the metro employed fewer than 100 people, and 95 percent had fewer than 50 workers. The abundance of locally owned specialty shops also contributes to the city’s unique character, says Heidi Reiber, director of research for the Economic Development Coalition, an arm of the Asheville Area Chamber of Commerce.

Franzi Charen, co-owner of Lexington Avenue’s Hip Replacements boutique and director of the Asheville Grown Business Alliance, agrees. “Our local businesses define the vitality of downtown,” she points out. “Out of the 1,448 businesses in the 28801 ZIP code, 88 percent have less than 20 employees, and 55 percent have one to four employees.”

Less is more

Perched at the corner of Haywood and College streets, Spiritex embodies the idea that less is sometimes more. Founded in 2005, the fabric design firm and retail establishment specializes in organic cotton apparel. “It’s a take on the traditional textile industry in North Carolina,” notes Corey Jones, operations manager and information technician. “It’s a small company, so we all pitch in.”

The operation’s intimate scale enables it to have a hand in every phase of the production process and to develop close relationships with its suppliers and contractors. “Creating a sustainable lifestyle for the people involved in our production is important to us,” says Jones. “We know the farmers that grow the cotton; we know the guy that runs the gin. Every step of the way, we can say, ‘Hey, Ted, how’s it going today?’”

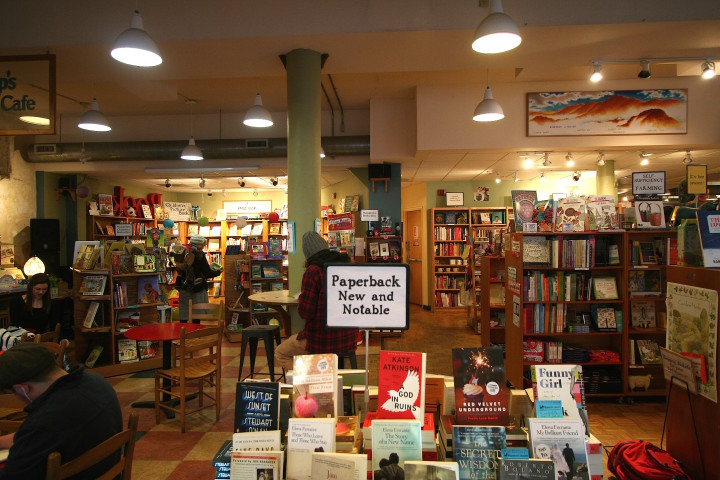

Down the street at Malaprop’s Bookstore/Café, General Manager Linda-Marie Barrett says having strong relationships with co-workers increases overall efficiency. “We are fortunate to have an incredibly talented staff,” she says. “They make running a small business less of a challenge, because they work hard and understand the importance of our success.”

That cooperative atmosphere, says Barrett, also extends to the other local booksellers. “Malaprop’s works together with our community of bookstores,” each of which has its own niche. “We find that through working together, we raise the profile [and] value of what we do in our community.”

Growing pains

Not all small, indie businesses are clustered downtown. But wherever their owners opt to set up shop, it’s imperative that they fully understand the real costs of starting a business, notes Walli Ann Wisniewski, who left a college teaching position to open The Tennis Professor on Merrimon Avenue last year. “However much money you have to open the doors of your business, multiply that by at least three times,” she recommends. The first few months, she notes, have been a learning process. “I didn’t know that I would be ordering spring lines as soon as I opened my doors in the fall. That was a challenge.”

Understanding the ebb and flow of a seasonal market can be difficult, Charen concedes. “One thing I’ll never get used to is the fluctuations from month to month. Every year is different.” But her advice to new business owners is simple: “When I see them panicking because they didn’t have any business that week, I tell them to relax. They’ll come back.”

Like many other specialty firms, The Tennis Professor banks on the personal, face-to-face connections and experience it offers customers, including the chance to try out merchandise before buying, with trained staff available to provide guidance.

“We have over 30 rackets to play with through our demo program,” she notes. “The larger sports chains that may carry gear don’t specialize in tennis, and our vendors supply us with a specialty-store line of product that bulk stores just don’t have.”

Thinking outside the box

To survive amid intense competition, small businesses also need to be creative. The Regeneration Station in Oakley, for example, is the offspring of Junk Recyclers, owner Tyler Garrison’s online resale operation.

Opened in 2012, the business “came about when he realized he needed a storefront to sell all the things he was picking up under Junk Recyclers,” says Nikki Allen, who manages The Regeneration Station. By refurbishing used items for resale, the storefront can offer a wide variety of products at a fraction of the usual cost.

“Our business model gives us the ability to create a culture and integrate entertainment and shopping into an experience that brings customers back again and again: something you can’t find online or in a big-box store,” says Allen. “In addition, we can offer a better product at a cheaper price.” But that doesn’t mean it’s easy. The biggest challenge, she says, is “adapting our new, often rebellious ideas into existing molds of traditional business operation.”

Limited resources typically require indie business owners to wear a variety of hats. “The hardest part of running a small business is that you have to be the expert in everything,” says Jenny Lane, co-owner of downtown clothing boutique f r o c k. She opened the Battery Park Avenue boutique with her mother, Betsy Bradfield, in April 2008. “We are in charge of marketing and promotion, regular social media posts, merchandising, setting the atmosphere inside the store, bookkeeping, inventory, communication with designers and vendors — it’s a lot!”

The key, continues Lane, is to understand your strengths and limitations. “Standing out in our market is all about knowing our brand and representing it in everything we do. We can’t be the best at everything, but we can be the best at being frock.”

Understanding local needs

Several local businesses have felt sufficiently established to open a second location. Epic Cycles, a Black Mountain bike shop, launched its West Asheville store a little more than a year ago. “Haywood Road has one of the highest bicycle counts in the state,” reports head mechanic Randy Collette. “Meeting the needs of the daily rider is very important to us.”

Each store, he notes, has a distinct clientele, and “We can tailor our offerings to both locations,” ultimately broadening their customer base.

Dancing Bear Toys, an Asheville staple since 1989, creatively incorporated some of the existing infrastructure into its design when it moved to Kenilworth Road in 2013. “We kept the bar from when it used to be a Hooters — now we call it the game bar,” store manager Jordan Castelloe explains. “It’s been a huge hit with our customers. Sometimes we have couples come in on dates just to play games!” A Hendersonville branch has been open since 1997.

Dancing Bear goes the extra mile to connect with its customers. Playful, handwritten signs adorn store shelves; demo toys are readily available for trying out. “We work hard to provide a fun, interactive shopping experience,” notes Castelloe. “Big business’s profits come from number crunching, essentially reducing your customers to data points; for a small business, your profits come from understanding the community’s needs and figuring out innovative ways to meet those needs.”

Convenience vs. sweetness

In an age when the Internet dominates many facets of American life, local businesses have taken various approaches to the digital dimension. At Spiritex, Jones estimates that online commerce accounts for almost two-thirds of total sales. “With all the involvement, time, energy and effort that goes into brick-and-mortar, the returns really aren’t that great,” she says. A website, on the other hand, gives customers a store that’s “open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, all over the world, instead of 10 to 7 in Asheville.”

The Internet also enables businesses without a large marketing budget to advertise effectively via social media. Malaprop’s, says Barrett, can “connect more intimately with our customers on various platforms — our email newsletter, Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr — bringing what we do and what’s available to our customers’ attention, which brings them into our store.”

Other local businesses, though, have made a conscious choice to limit their online presence. “When you decide to go online, you have to understand that you are putting yourself in a place where you have to compete directly with places like Amazon.com,” notes Charen. Hip Replacements, she says, “hasn’t been convinced that’s a direction we want to take the store in. In fact, we’ve opted not to.”

And frock, says Lane, doesn’t offer an online retail site “for a couple of reasons. Local and personal is what we do: Why complicate it?” Many consumers, she believes, appreciate the intimacy that only face-to-face interactions can offer. “Visiting your local hardware, music, clothing or pet store is one way to expand your community and be a part of something. You see the same faces, and there’s a sweetness in that.”

Keeping Asheville real

Rik and Elizabeth Schell have operated Purl’s Yarn Emporium on Wall Street since 2010. Former customers, they bought the store from Lindsey Rey to keep it from closing. “I taught my husband to knit and he more than liked it, so we followed through on our crazy plan,” Elizabeth reveals. And despite the challenges of parking and rent increases as the city’s popularity grows, she adds, Asheville is still “a great place to own a small business.”

“It’s so rare to have a downtown like ours that you can walk around, that includes original buildings, that isn’t — yet — completely overrun by chain stores,” she observes. “Businesses like ours help keep Asheville real.”

Laura Cooke, who sells her ceramics out of the Phil Mechanic Studios in the River Arts District, says the strong support from her fellow artists has helped her business flourish. “Potters are always helping each other out — giving advice, firing kilns together, lending materials,” she reports. “They’re the closest thing I have to co-workers.” The thriving arts community, adds Cooke, also “speaks to Asheville’s commitment to handcrafted and local.”

The building, however, was recently sold to Texas developer James Lifshutz for nearly $2 million, stirring fears that rising property values and taxes could threaten RAD artists as well as downtown indie boutiques. In 2013, the adjacent Kent Building was sold for $2 million.

Asheville, notes Charen, is “so successful in some ways that people come here only to find high real estate prices and no place to live, or no living-wage jobs. You see more high-end boutiques in downtown now; that development has kind of moved on to the River Arts District, where you see this kind of gentrification creeping in.”

In a Jan. 25 press release, Lifshutz, who developed the Blue Star Arts Complex in San Antonio, said: “Art is in the DNA [of the Phil Mechanic building], so it must continue to be featured prominently in the mix. What will the final mix be? My intent is to spend the next year or so figuring that out by way of a planning effort that will involve my consultants, the city of Asheville, current tenants and other stakeholders.”

Cooke, meanwhile, says, “There is concern that I could be priced or forced out. Right now, I’m assuming I have at least a year. Hopefully the new owner will give us warning if he decides to take the building in a different direction, so we’ll have time to look for new space.”

Following the money

And as the city’s reputation as a regional tourist destination continues to grow, Charen maintains, supporting local businesses becomes ever more important. “Asheville’s hit the green light for the chain stores: They’re seeing the money.”

With an influx of big chains, she contends, come rising real estate prices, cheaper foreign products and a loss of the very character that has attracted people to the city. “When you have chains come in, it creates this race to the bottom. The entire landscape changes for everyone.”

To that end, Charen has taken a step back from direct involvement in running Hip Replacements in order to devote more time to the bigger picture. She was recently appointed to the Downtown Commission, and she’s also looking to focus more on Asheville Grown and on coaching other local startups. “One of the things I would personally like to start doing is consulting and working with entrepreneurs to help them with their businesses,” she reports. “I’m also interested in business succession [handing off a business or key leadership positions to someone new], especially in the manufacturing field — which, for me, is a key part of any local economy.”

In addition, Charen wants to bring more area residents downtown. “I’m grateful for the tourism industry, but we’d rather have our bread and butter be from the locals, because it’s more sustainable,” she explains. “Whenever the tourists stop coming, the chain stores are out of here, but our businesses and our employees are still going to be here.”

And even if the individual enterprises are small, their collective economic impact is significant. “Local businesses,” notes Charen, “generate three times more value per dollar in the community than when you shop at a chain store. The secondary jobs — bookkeepers, Web designers, accountants and lawyers — small businesses hire locals to do that.” National chains, however, “centralize that stuff, and all that money leaves our community.”

All together now

Local indie business owners praise the work of groups like Asheville Grown and UNChain AVL (a recent project that’s taken a more assertive approach to the same concerns, organizing protests and lobbying City Council).

“Programs like Asheville Grown and other like-minded ‘buy local’ campaigns are really drawing awareness to the huge impact of spending locally,” says Lane.

Costelloe agrees, saying, “Ashevilleans really take the message to heart.” And for these entrepreneurs, “It really feels like we’re all on the same team. It’s not enough for one small business to make it, or even a handful. It takes a network to keep the local economy afloat.”

Economics aside, adds Jones, supporting local businesses helps sustain the unique atmosphere that so many folks have helped create. “Why did we choose to live here?” she muses. “You really have to step back and think about that. It certainly isn’t because it had strip malls!”

Charen concurs. “Tourists come here to experience what we have that’s different. With so many other places, we’ve seen it inevitably happen that they lose the interesting things that made it special and they become ‘Anywhere, USA.’ I hope Asheville won’t go in that direction.”

Our local, independent businesses are a critical part of the fabric of Asheville. I’m proud to support our entrepreneurs by rolling out a new $1,000,000 loan fund called Buncombe Community Capital, and I’m honored to have the endorsement of Franzi Charen, Kelly Prime, Willie Mojica, Andrew Dahm, and other Asheville Grown business leaders!

Here’s more information on Buncombe Community Capital ———-> http://www.citizen-times.com/story/news/local/2016/01/30/small-business-loan-fund-tops-councils-big-ideas/79561814/

And here’s a link to a new page at my website. It’s called Community Voices, and it highlights community leaders like Franzi Charen who are supporting my campaign for Buncombe County Commission ————-> http://www.gordonforbuncombe.org/gordon-calls-for-indigenous-peoples-day/