Sewage is something most people choose to ignore — until it becomes a problem. But if you live near or frequently pass by Woodfin’s riverfront, chances are you’re familiar with the less-than-pleasant odor that sometimes emanates from the plant operated by the Metropolitan Sewerage District on Riverside Drive.

While it may not be the most appealing of fragrances, the smell is the byproduct of an innovative, vital agency. With little fanfare, MSD’s team of technicians and engineers work around the clock to process millions of gallons of wastewater each day into harmless byproducts, while maintaining an extensive network of sewage lines that crisscrosses much of Buncombe County.

To fulfill its critical mission and increase its capacity to deal with a growing service area and customer base, MSD is in the midst of a $266 million capital improvement project, which will help ensure that the community’s waste is properly handled and safely disposed of.

At your disposal

It’s hard to miss the MSD plant, located on Riverside Drive in Woodfin. Two geodesic domes rise over a series of white-roofed shelters, bringing to mind the midcentury inventor Buckminster Fuller, who developed the concept of the geodesic form while teaching at Black Mountain College.

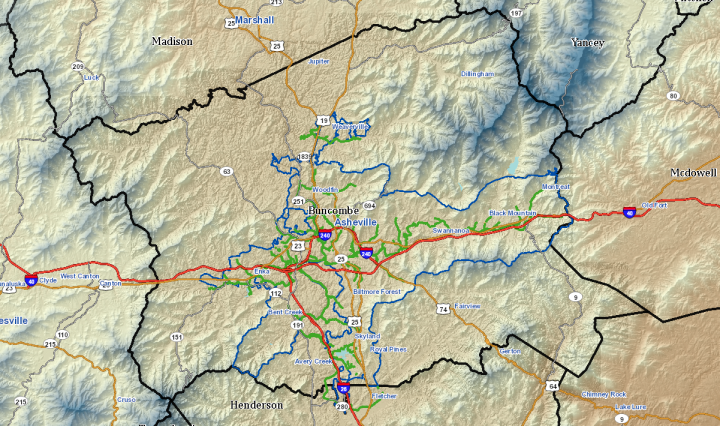

Established in 1962 by the N.C. State Stream Sanitation Committee, MSD is charged with constructing and operating facilities for the treatment and disposal of the sewage generated by the municipalities of Asheville, Biltmore Forest, Weaverville, Woodfin, Montreat and Black Mountain, in addition to 10 special districts of unincorporated Buncombe County land and parts of northern Henderson County.

“Prior to MSD’s existence, raw sewage would be discarded directly into the French Broad River,” says Jerry Vehaun, who chairs MSD’s board of directors. “Today, we have a clean river which is constantly used for recreation purposes such as boating, fishing and so forth [because of MSD].”

The largest public entity in North Carolina to be registered under ISO 14001, a set of standards established to guide organizations on environmental best practices, MSD has frequently been recognized with awards. In 2003, it was one of two facilities nationwide to receive a National Environmental Achievement Award for its Pipe Rating Project, which compiles closed-captioned footage, test results and maintenance records into a comprehensive database that tracks the condition of the sewer network.

“We provide waste treatment services to over 130,000 people,” says Tom Hartye, MSD’s general manager. “Environmental stewardship is at the core of what we do here.”

Process of elimination

That commitment is embodied at MSD’s French Broad River Water Reclamation Facility, which Hartye says may be the largest of its kind in the world.

As wastewater arrives at the facility, solid waste is separated from the main volume of the flow. Trash is carted off to the landfill, while a three-tiered incineration tower concentrates the remaining solid sludge into ash, says Roger Edwards, a retired N.C. Department of Environmental Quality employee who now serves as operations manager at the plant.

Unlike conventional wastewater treatment facilities, where processing lagoons sprawl over vast expanses, MSD’s facility maximizes the limited acreage at its riverside site by utilizing a system of rotating biological contactors — spinning, corrugated waterwheels laden with bacteria that break down and consume the contaminants found in sewage.

“We’re essentially bug farmers,” jokes Edwards. The 152 rotating mechanisms comprise a surface area equivalent to 400 to 500 acres, providing space for microorganisms to treat the 21.6 million gallons of wastewater that flow through the facility on an average day.

After the bacteria have consumed the pollutants — a process that takes about six hours, according to Edwards — the water is sterilized with a sodium hypochlorite solution (essentially, chlorine bleach) and sluiced back through a network of water clarifiers. The treated water is then dechlorinated and released into the French Broad River.

The MSD plant’s processes yield water with levels of suspended solids and contaminants well below what state regulations allow, says Edwards, adding that the water that leaves the plant generally has a lower bacteria count than the river it’s going back into.

To offset the energy required to power the MSD plant and its pumping stations across the county, the agency operates a hydroelectric facility which is capable of generating 2,880 kilowatts per hour, depending on the French Broad River’s flow and water levels. In 2015 alone, MSD avoided $435,000 in costs by utilizing the hydroelectric facility.

Thinking ahead

MSD’s efforts to upgrade its system with high-efficiency, low-impact technologies and strategies have paid off significantly in the past couple of decades. Sanitary sewer overflows have declined from 288 cases in 2000 to only 37 in 2015, notes Hartye.

Using closed-captioned television footage and “no trench” technology, MSD officials can identify obstructed or damaged sewer lines and replace or repair them without digging down from the surface. Data collected from sewer cameras are stored and cataloged in MSD’s Pipe Rating System, allowing staff to keep tabs on the status and maintenance history of its entire pipe network.

At the plant, recent upgrades — including a $10 million AquaDisk polishing filter system and $7.4 million in upgrades to MSD’s incinerator and air emissions system — have increased the amount of contaminants the agency can remove from wastewater, and reduced the labor, time and resources needed to do so.

“We believe in trying to stay ahead of things, in regards to maintenance and infrastructure,” says Hartye. By being proactive, he adds, MSD saves its customers money and can put more resources toward improving the system, rather than scrambling to fix problems after they occur.

Leaky pipes

Staying ahead of the curve is crucial, in light of the long list of challenges MSD hopes to address in the coming years. “Buncombe County is growing, so MSD needs to keep up with the growth but at the same time make sure that the older infrastructure is maintained,” says Asheville Vice Mayor Gwen Wisler, who’s also a member of MSD’s board of directors. “This can be very cost-prohibitive.”

Since taking control of municipal wastewater collection systems in 1990, MSD has invested over $300 million in replacing and upgrading over 1 million feet of sewer mains, roughly equivalent to 25 percent of the sewer system. The agency plans to upgrade an additional 250,000 feet over the next five years.

Many of these local sewer lines date back to the early 1900s, and are in poor condition, notes Hartye. This includes obsolete, deteriorating clay pipes and, incredibly enough, reinforced wood fiber “Orangeburg pipes” in some instances.

Widely used as piping for electrical conduits in the 20th century, excess Orangeburg pipes were often sold to small municipalities at discounted rates to use for septic systems, Hartye says. “These things have pretty much disintegrated,” he notes. “Whenever we come across one of those, we have to replace the line right away.”

Antiquated, damaged lines not only leach materials into nearby soil and groundwaters, but also allow dirt, grit and stormwater to infiltrate MSD’s system. Rainwater also enters the sanitary sewer system as inflow through pipes or cross-connections with the storm sewer system. According to Hartye, one-third of the 8 billion gallons MSD treated in 2016 came from “infiltration and inflow,” which can strain MSD’s infrastructure during during storms.

21st century sewage

While MSD currently treats about 20 million gallons of water a day at its Woodfin plant — which represents about half its maximum capacity — current construction projects will increase its storage capabilities and improve its efficiency.

Upgrades include the recently completed replacement of MSD’s influent pump station, which allows plant operators to control the energy output of the pumps used to pull waste into the treatment facility to match the flow coming into the plant on a given day, conserving electricity and prolonging the life of the pumps, says Edwards.

The plant headworks project, launched in 2016, will add new screens and grit removal technology to help filter out solid waste. In addition, two decommissioned storage tanks (the geodesic domes visible from Riverside Drive) will be renovated to provide additional storage space, which will allow MSD to treat wastewater more thoroughly during high-flow storm periods. The plant headworks project is expected to be completed by the end of 2018.

The $10 million High Rate Primary Treatment Project is scheduled to begin by spring. “The technology for this type of clarification process is fairly new and involves quickly and efficiently settling out all the nondissolved solids within the waste stream,” explains Hartye. “The more effective this treatment is, the better the treatment processes downstream can perform in removing the dissolved fraction of the waste stream. MSD’s treatment process already removes over 95 percent of the incoming pollutants and is in many ways cleaner than the river it is going back to. The remaining 5 percent is what we are after with these new technologies in an effort to get it to be closer to be pure water.”

“Facilities such as this cannot afford to have breakdowns because of lack of maintenance or using older technology,” says Vehaun. Plant workers got a glimpse of what such a disaster scenario might look like on April 30, 2013, when a 400-pound gate blew out of position during a replacement of one of the plant’s pumps, spilling raw sewage into the nearby French Broad River and creating a “code red” at the plant. (See “Code Red: How this team helped stop MSD’s record April 30 sewage spill,” June 19, 2013, Xpress)

Investing in capital improvements helps to avoid such catastrophes “by keeping us up-to-date with the latest technology and to ensure that all equipment is state-of-the-art,” Vehaun adds.

The current capital improvement projects, when finished, “will increase both the service level of treatment as well as capacity for future customers,” says Hartye.

Trash talk

In tandem with these upgrades, MSD is engaged in communication efforts to dispel misconceptions about its work and inform residents on proper use of the sewer system.

The agency’s “Can the Grease” program provides education on proper disposal methods for cooking greases like animal fat, coconut oils, and other nonwater-soluble materials.

“Flushable” wipes are another problem product MSD is working to address with the public, says Hartye. “They’re advertised as ‘flushable,’ but in reality, they don’t break down so easily,” he notes. “If you swirl a piece of toilet paper around in water for a couple minutes, you’ll see it basically disintegrates, but these wipes don’t do that.”

MSD also provides tours of its facility for students and citizens, notes Edwards, and a variety of information is available through the agency’s website, including a virtual tour.

Students from the French Broad River Academy, whose boys campus sits near the MSD plant in the Riverside Business Park, learn about the importance of infrastructure for functions like waste management from their neighbor.

“That’s one of my favorite field lessons that we do,” says the school’s co-founder Will Yeiser. “Our social studies teacher does a unit about how small ancient cities dealt with sewer and trash, and how big urban areas have to deal with it. We tour the plant and see firsthand what’s going on. Everyone’s grossed out at first, but if you think about it, it’s a pretty awesome thing.”

Doing the dirty work

Edwards hopes expanding the public’s understanding of MSD’s role will inspire more young people to consider the profession. “We need younger folks to come into this line of work,” he says, encouraging those interested in learning more to check out local certification programs at A-B Tech and other regional schools. “There’s room to grow professionally. Plus, you have the best job security out there: The need for MSD isn’t going away.”

And while residents might not like the smell emanating from the plant now and again, that smell would be a lot more prevalent — and dangerous — without MSD to do the dirty work, Wisler says. “Unclean water leads to disease, as we have seen from underdeveloped countries and, unfortunately, even some of our domestic cities,” she notes. “MSD processes and service delivery ensure that our county has a healthy source of water.”

We’re fortunate to have such a well-managed system in our neck of the woods. Thanks to all the folks who keep it running.

And thank the gods that MSD doesn’t have to worry about taking over Asheville’s water system too. Geez, what a bad idea that was.

http://saveourwaterwnc.com/