Ask most folks what characteristics best define Asheville, and it’s a safe bet that religious devotion won’t be at the top of the list. Despite having been dubbed a “cesspool of sin” by the late state Sen. James Forrester, however, this city has been a hotbed of religious activity since day one.

From Church Street’s grand old houses of worship to the East End’s historic African-American churches, faith congregations have played a central role in Asheville’s growth and development. The city is home to more than 300 Christian churches, and myriad faith-based conference centers and religiously affiliated schools dot the surrounding landscape.

There are also three Jewish congregations, several Pagan groups, a Muslim mosque and a vibrant Buddhist community, just to name a few, and since they operate relatively close to one another, they sometimes intermingle in surprising, even humorous ways.

“One of my favorite elements of Jewish life in Asheville was Chabad House being situated between a tattoo parlor and a head shop” on Merrimon Avenue, says Rabbi Justin Goldstein of Congregation Beth Israel. “Only in Asheville would you see that. It’s so perfect.”

But while the city’s spiritual life may be diverse, shifting demographics and evolving notions of religion’s role in daily life have many historic congregations reconsidering the part they play in local culture — and how best to address a changing community’s concerns.

City on a hill

Several local congregations can legitimately claim to be as old as Asheville itself. First Presbyterian Church, for example, was founded in 1794, says the Rev. Patrick Johnson. “As a downtown church in a historic building, our history is with us every day,” he says.

Nonetheless, Johnson maintains, First Presbyterian’s most attractive quality is its ability to grow with the times. “What compelled me to come here is their commitment to sharp theological thinking and deep engagement with the world, both of which are rooted in really dynamic worship,” he says.

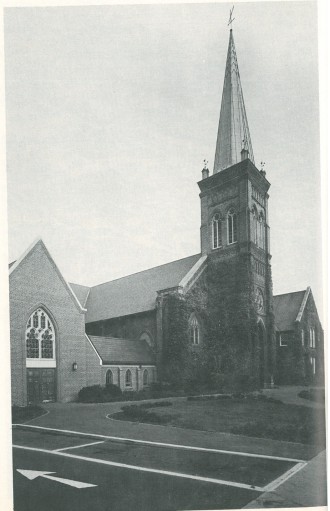

Other local historic congregations share that commitment to community involvement. Built in 1896 at the behest of George Vanderbilt, the Cathedral of All Souls in Biltmore Village was founded on the idea of providing a community space and resource, says the Rev. Todd Donatelli. “It wasn’t just a chapel for [Vanderbilt’s] daughter to get married, as some folks thought,” he emphasizes. The Episcopal church “understood from day one that it was not to be just a place for us to come and take care of our own needs, but a place of life for the whole community.”

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Asheville was nationally known as a center for the treatment of tuberculosis, which was rampant in the U.S. at the time. That mission was reflected in the original name of Congregation Beth Israel, which was founded in 1899. “The name of that very first congregation, because health was near and dear to our heart, was Bikur Cholim,” notes Alan Silverman, Beth Israel’s member engagement team coordinator. “That’s a Jewish commandment that means ‘visiting the sick.’”

Sanctuary

For Asheville’s minority populations, these early centers of worship were also a place where parishioners could find shelter from racial and religious discrimination. “All of the social clubs in town were limited [to white Christians],” says Goldstein. “Jewish communities would build their own facilities, so to speak, to be able to enjoy those kinds of gathering spaces.”

St. Matthias Episcopal Church, which celebrated its 150th anniversary last year, is widely acknowledged as Asheville’s first African-American congregation. Founded late in 1865 as the Freedmen’s Church, it was set up to serve formerly enslaved people, says the Rev. Gerald Prickett, St. Matthias’ present-day rector. “That was the only black educational institution [in Asheville], including for adults” at the time, he notes.

St. Matthias continued to be a center of black life in the city for decades, attracting doctors, lawyers and celebrated figures such as mason James Vester Miller. Miller and Sons Construction built the Municipal Building, which houses the city’s police and fire departments, as well as St. Matthias’ 1894 brick building and other local African-American churches.

To this day, “It’s the only [local] Episcopal church with a significant black population at all,” Prickett points out.

But while Asheville might have displayed the same segregationist tendencies that were widespread at the time, the city also showed early signs of religious cooperation that were seldom found elsewhere in the South. On the eve of Beth Israel’s grand opening in 1916, for example, the newly built synagogue burned to the ground. “Within a few hours of hearing about what had happened, there were half a dozen churches whose pastors, priests and ministers came forward and offered to open up their sanctuaries,” notes Silverman. “They said, ‘We’ll cover up the crosses, and you can use it however you need.’ That, in my mind, kind of started this collaboration between our congregation and the greater Asheville community.”

Changing tides

Attendance at historic congregations held steady well into the 20th century. Beginning with the turbulent 1960s, however, evolving social views of the nature and purpose of religious worship posed a new set of challenges for the area’s historic churches.

“The American religious landscape has gone through various periods of expansion and retrenchment,” says Rodger Payne, who chairs UNC Asheville’s religious studies department. “You can really see what’s going on in the larger culture as you look at what religious groups Americans are supporting, what ones are declining and which new ones are being brought along, discovered or rediscovered.”

According to the most recent edition of the Pew Research Center’s “America’s Changing Religious Landscape” studies, a quarter of adults now consider themselves “spiritual but not religious,” up 8 percentage points from 2012. A 2015 report, meanwhile, found that the number of Americans who identified as “unaffiliated” had risen from 16.1 percent of the population in 2007 to 22.8 percent in 2014.

There are myriad reasons for this shift, says Payne. “So-called millennials are sort of turned off by the current polarization of political and cultural life,” he notes. “They see these institutionalized religions taking sides in the culture wars, and they don’t really want to identify on one side or the other.”

Growing populations of Americans with roots in Asia, Africa and the Middle East have also introduced new forms of belief and worship into popular culture. “Literally, as Pew indicates by the title of this study, the landscape is changing,” says Payne.

Not your mother’s church

This trend has not gone unnoticed by local religious leaders. “I think, particularly in the 1950s to ’70s, if you had a church and opened the doors, people showed up,” says Donatelli. “It was so easy in a lot of ways that churches got into the habit of thinking they just had to be there.”

But though All Souls’ membership still numbers in the hundreds, how those folks engage with the church has changed significantly. “To be a regular church member even 20 years ago meant you were probably there three out of four Sundays of the month,” Donatelli points out. “Nowadays, people might be two Sundays a month as an average,” while others prefer to attend Wednesday services and other weekly activities in lieu of the traditional Sunday Mass.

Meanwhile, changes in the city’s demographics have had a dramatic effect on other local congregations. St. Matthias, for example, underwent a dramatic shift as a result of urban renewal efforts and gentrification in the city’s East End over the last half-century.

“The population of African-Americans began to move away from this area,” Prickett explains. “We have only two or three members who still live in this neighborhood; others are either out toward North Asheville or Fletcher.”

Beth Israel’s congregation has actually grown in the last few decades, due in part to new converts to Judaism, says Silverman. “There’s a rabbi I knew once who had an interesting play on words when it came to that phenomenon: He said, ‘We are no longer the chosen people; we are the choosing people.’”

Like their Christian counterparts, however, the way Jewish congregants interact with the synagogue has shifted in recent years, notes Goldstein. “It’s not just the absence of people but, in an energetic sense, a paradigm shift. This whole idea of being spiritual but not religious is really just a subtle way of saying that the institutions that exist at my disposal are not meeting my needs.”

Evolution of faith

Faced with these changes, historic congregations of whatever denomination have embarked on a re-examination of the way they interact with their members and the wider Asheville community.

For some, that means introducing new programs to boost attendance. In response to declining membership in the 1990s, for example, St. Matthias began holding organ concerts on the first and third Sundays of the month, says Prickett. “They were free, and the donations went to the church,” he says. “Up until the early 2000s, those Sundays filled the church, and it was able to rebuild the organ and do a lot to make things better here.”

Other faith organizations have adapted their buildings’ physical layout to fit contemporary aesthetics. “Historic churches carry generations of traditions and memories that are often built into the architecture of the building and sealed in the hearts of the people,” notes Johnson of First Presbyterian. “The deep question we must ask is what’s a treasure to keep and what should be changed for a new generation?”

In 2000, All Souls launched a massive renovation of the cathedral, which hadn’t been substantially upgraded since its construction. The changes raised a complex question of how to balance tradition with present-day parishioners’ needs. “Anthropologically, there’s reasons why liturgy has compelled people,” says Donatelli. “And yet, if we just keep tramping out 1800s-era hymns, that doesn’t always speak to people. We respect the old and understand it has meaning for us, while knowing it always has to evolve.”

Congregation Beth Israel, currently in the midst of its own renovation project, has taken the opportunity to reject the 19th-century European model of a synagogue in favor of a more traditional layout. “Visit most synagogues around the country and you’ll find pews, just like in a church, facing one direction,” notes Goldstein. “That is not a historical Jewish model for a sanctuary; that’s a layout that was adopted in Germany from the Lutheran tradition. The idea was if you acted like them, then you would be treated like them.”

The new layout, he adds, will seat worshipers in a circle around the prayer leader during services; it will also give members more access to the rabbi’s office. “Part of our motivation in reimagining is what does a 21st-century sanctuary look like?” continues Goldstein. “I think there’s a big push away from the buildings, which is good, in my opinion. There is a sense in which real spiritual work happens in the world. I think part of the rejection has been these kind of austere buildings.”

Being present

In the early 2000s, Beth Israel disaffiliated itself from the Conservative Judaism it had adhered to for decades. “This idea of identifying through a particular denomination was no longer speaking to the needs of our community,” says Goldstein, particularly in regard to accepting interfaith families and same-sex partnerships.

“We felt like that was not our authentic self to exclude those groups,” adds Silverman. “What we have found so far is that if you de-emphasize the institution and emphasize the people — the hearts and the minds and the connections that call this institution home — that’s something that becomes very attractive. I think it has been one of the most liberating, positive decisions we’ve made in a long, long time.”

Other congregations have tried to bridge generational and societal gaps by reaching out to the wider Asheville community to learn about its needs and experiences. All Souls, for example, is currently hosting a series of talks by community leaders on the struggles of the city’s marginalized populations. “We’re having people from health care, education, housing, mental health coming and talking about the history of our neighborhoods in Asheville, racial equity and the lack thereof,” Donatelli explains. “We’ve also been going out and interviewing leaders in the community to say, ‘What do you see that’s working well? Who’s working together? Where are the needs?’ — and then as a community listening to where the spirit might be inviting us to be engaged in those areas.”

In addition, All Souls has made its space available to a variety of religious and secular organizations as a meeting place. “Any night you come here, there are multiple groups — community groups, nonprofit groups,” says Donatelli. “One of the things I love is when I walk out at night and I see all kinds of people standing across the street [at the church], and I realize I have no idea who these people are. God speaks to all people in different ways, and we’re just simply called to be in relationship with one another.”

Helping hands

Giving back to the community, especially those struggling to meet their basic needs, is a central focus of every faith group interviewed for this article. Members of those congregations volunteer with countless local organizations and causes.

“At St. Matthias, a significant item in our budget is outreach,” says Prickett. “We have, in the past, volunteered at the women’s correctional facility in Swannanoa; we participate in Habitat for Humanity; we have people who volunteer at [Asheville Buncombe Community Christian Ministry] and a lot of other places.”

Donatelli sees his congregation’s work in the community as a reflection of Christianity’s most basic tenets. “Jesus didn’t sit in his house of worship and wait for people to come to him,” he notes. “Hopefully, what faith communities are providing is the rhythms and practices of life that help us feel loved and, from that love, feel less anxious, so we’re not operating out of our fear but from a general trust. If faith communities aren’t doing that, then close the doors.”

People of different religions are also working to understand one another’s viewpoints and beliefs: Beth Israel hosts several Christian groups each year that come to learn about the Jewish roots of their faith, says Silverman. In addition, Beth Israel’s leadership periodically meets with local Islamic leaders and participates in interfaith conferences.

“We get a lot of people coming in who are searching for something,” he notes. “Whether they find it at our synagogue or Jubilee or Beth HaTephila, it doesn’t matter to us. Success is when they land in the right place for them.”

Searching for connection

Only time will tell how Asheville’s historic congregations will fare in the future, but Goldstein believes that the changes in American religious belief are just beginning. “There’s a major shift right now, but at what stage we are in that shift is hard to know,” he points out. “What I think is pretty clear is that things will never be the same after.”

For those still searching for the right fit to address their spiritual needs, Donatelli offers this advice: “Throw yourself into it. Look at stuff and listen to your body. If it’s energizing, then maybe that’s the spirit’s connection in you.

“It’s going to be different for everybody,” Donatelli stresses. “The stuff I’m interested in may not be what you want: You have to find what feeds you best.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.