Asheville’s voters will decide in November whether the city will take on a major — $74 million — taxpayer-financed debt load for the first time in decades. Supporters say the funds will support the city’s current growth by creating or updating vital infrastructure. Critics say taking on such heavy debt is irresponsible.

Some of those critics raise the specter of the Great Depression, when Buncombe County had one of the highest levels of debt per capita among all United States counties. Even former Vice Mayor Marc Hunt, who supports the current bond measures, notes, “The impact of the 1920s made it so that economic development for decades following the 1920s was very difficult, and it was only around 1990 that the economy of Asheville began to recover.”

Asheville’s municipal debt crisis, spanning 1927-36, appears, in retrospect, to have been the consequence of a multiyear perfect storm. By 1928, over half of the city’s collected revenues were being used to pay off its debt. On a single day in November 1930, eight banks in the region closed. By 1932, Buncombe County’s 98,000 residents were on the hook with bondholders to repay a mind-numbing $158.8 million — $2.8 billion in today’s dollars, or over $28,000 per person. Because the county and city debt were consolidated in a 1936 agreement, Asheville labored in the shadow of that entire amount.

Boom turns to bust

One victim (or villain) of the times was Asheville Mayor Gallatin Roberts. An attorney, Roberts served in a variety of elected positions, including county attorney, state legislator and two stints as the city’s mayor.

At the age of 49, Roberts came into mayoral office for a second time in 1927, having previously served from 1919-23. This go-round, he had campaigned on pledges to reignite a once-promising economy that had faltered in the face of worsening financial conditions — conditions that would soon become the Great Depression. Roberts’ efforts quickly became mired in a financial scandal that helped push the city near bankruptcy and eventually led to his death.

A real estate frenzy in 1925 had sent Asheville’s land values and hopes soaring. Today’s development boom of new hotels and other real estate ventures may seem dramatic, but it pales in comparison to the city’s frenzy during that earlier period.

C.R. Sumner, a reporter at the time for the Asheville Citizen, described the scene as “so cockeyed crazy as to make the opus of Jules Verne seem like the tamest of prose.” Real estate offices popped up overnight in high-rent spots near Pack Square, removing their front doors to make room for the brass bands and string orchestras they hired to play as enticements, Sumner recollected in an article dated March 16, 1956. Salesmen from the recently burst Florida bubble market came to Asheville, loading customers on custom-built touring cars to see land developments by day and throwing parties fueled by call girls and Prohibition-era alcohol by night.

Asheville’s population grew from 20,000 in 1920 to more than 50,000 in 1930. In 1924 alone, building permits brought in $4.2 million, several sources report.

Growth of this magnitude necessitated increases in municipal services, and Roberts’ predecessor, Mayor John Cathey, authorized spending over $15 million ($207 million in today’s dollars) on infrastructure. According to a 1934 University of North Carolina study — which categorized some of these expenses, such as the city’s new public golf course, as luxuries — the city improved its water service, paved roads and built a new art deco city hall designed by architect Douglas Ellington.

Barbara Whitehorn, the current chief financial officer for the city, imagines the time as being one of intoxicating potential, which clouded sound judgment. “It’s the Roaring ‘20s, the economy is booming, people are thinking, ‘We can do anything. We’re the Paris of the South,’” she muses. When real estate values began to decline in 1926, those lofty dreams were put in jeopardy.

A mayor in crisis

When Roberts took office in 1927, he found a web of debt slowly suffocating the area. Some of it was partially hidden at first: Throughout the 1920s, individual districts, such as Biltmore Village and Swannanoa, were able to issue their own debt without notifying one another. This practice resulted in excessive borrowing, as well as double spending when districts with overlapping boundaries borrowed money for purposes such as maintaining roads. Over time, the debt burden became overwhelming when the real estate market, which had begun to falter in 1926, didn’t bounce back, either. Between 1927 and 1933, house prices in Asheville dropped nearly 50 percent.

While the real estate decline certainly hurt the city, the 1929 stock market crash dealt the decisive blow. Asheville’s own “Black Thursday” took place a year later, on Nov. 20, 1930, when eight banks in the region closed — four in Asheville, three in Hendersonville and one in Biltmore Village (then its own district). Many people lost whatever money they had in those banks. The city itself had at least $3 million (1933 dollars) for the school budget alone in Central Bank and Trust. It appears from news reports that that money was lost. The dream of the Roaring ’20s had transfigured into a nightmare.

Throughout late 1929 and 1930, Roberts went to extreme, perhaps illegal, measures to save his city, according to an oblique mention by the state’s attorney general in an April 1930 editorial in the Asheville Advocate. To buy time, Roberts set up a complicated financial scheme.

The Central Bank and Trust of Asheville had been the major financier of the city’s development. In what seems to have been a quid-pro-quo relationship, the city kept its accounts at the Central Bank. The bank oversaw issuances of bonds and then gave the money to the city. The city deposited that money back into the bank, which could use those deposits to fund additional lending. According to a 1934 report by Chester F. Lewis from UNC’s School of Public Administration, “Asheville’s difficult position was rendered more difficult by the fruitless attempt to bolster the chief banking institution [Central Bank and Trust] with deposits of public funds, only to have the bank close in the end. With the closing of the banks holding public funds, the city was no longer able to meet current expenses and maturing obligations.”

Increasing desperation

“If we hadn’t had the crash, we probably could have paid off the debt and people never would have known the extent of the behind-the-scenes issues,” Whitehorn says. After the crash of the market and nationwide bank closings, though, the relationship between the city and its bankers became increasingly desperate.

A bank assistant cashier, Charles J. Hawkins, who was tasked with bringing promissory notes to Roberts, characterized the mayor as a nervous wreck of a man by 1930. In court testimony, Hawkins described the erratic behavior Roberts exhibited when he asked for the mayor’s signature: The mayor would instruct Hawkins to close the door to the office, and Roberts would pace back and forth, sometimes for minutes, before signing. Occasionally, Roberts would ask why the notes were being issued and inquire about the financial condition of the bank. Hawkins would then leave City Hall as inconspicuously as possible.

Black Thursday, however, spelled doom for Roberts. He resigned as mayor in December as evidence of the city’s financial mismanagement mounted. In 1931, the state legislature created a budget control board, which took over Asheville and Buncombe County’s major municipal services, according to a news article titled “County Board Has Authority Much Reduced,” held by the North Carolina Room at Pack Memorial Library.

Vestiges of this shift toward state authority (such as control of many local roadways and oversight of borrowing) continue to this day. Further, the people of Asheville themselves, according to Lewis’ report, lobbied the city government to change its administration style to the more transparent citycCouncil-city manager structure that is now in place.

A Dec. 6, 1930, editorial in the Asheville Citizen stated that while auditors found Roberts responsible for gross mismanagement, the newspaper had concluded neither he nor any locals personally pocketed government funds. But that meager vote of confidence was cold comfort to Roberts. Pack Memorial Librarian Betsy Murray, reflecting on biographical material from the N.C. Room’s Gallatin Roberts Collection, writes that Roberts had “spent his entire life trying to be the trustworthy, upright man that he wished his father [who had abandoned the family] had been.”

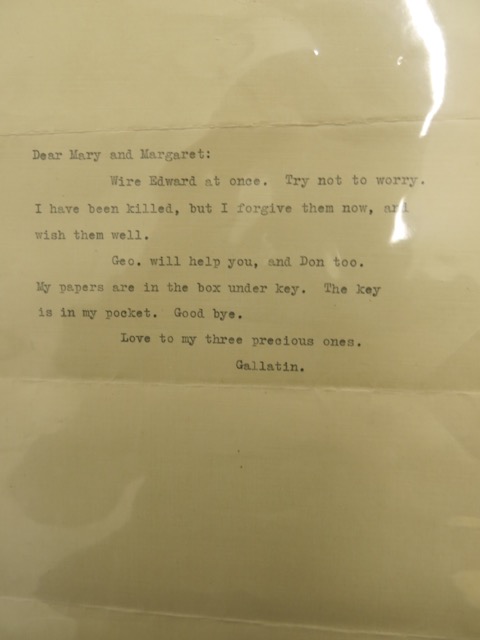

After his indictment — along with other officials — by a grand jury in February 1931 on charges of conspiring to misuse public funds, Roberts wrote three letters, one to his family, one to his close friend George Pennell and one to the people of Asheville. This third letter (published in the newspaper) concludes, “When I went into office nearly four years ago, I found millions of dollars of the people’s money in the Central Bank and I tried with all my soul to protect it. … What would you have done? … Would you have made an honest effort to save it?”

On Feb. 25, 1931, Roberts killed himself with a .38-caliber revolver in the bathroom of his law office.

Legal challenge

After Roberts’ death, more details emerged about the scope of the mismanagement. The new City Council asked a regional firm, R.C. Birmingham, to conduct an audit of the city’s finances. Along with the predictably dismal budget numbers, the firm also concluded that the city’s contracted auditor during the entire 1920s, Scott and Co., had created a “monumental farce.” The audit work reflected “rank stupidity,” the report states, “pervert[ing]” the city’s credit. Scott and Co., the report continues, also billed the government above-market prices for such peculiar services as an “advance of audit” and “balance on special audit, to apply on audit.”

When Roberts’ travails, the incompetence of the city’s auditor and other missteps came to light, the circumstances opened the possibility of challenging the validity of the bonds. It seemed worth a shot to city leaders, given the crippling alternative. In 1932, according to “An Onerous Pact,” an editorial published on Dec. 9 of that year in the Asheville Advocate, bondholders presented a settlement agreement to Asheville and Buncombe County requiring full repayment of $158.5 million ($2.8 billion in 2016 dollars) and waiver of the right to legally challenge the bonds.

The fiery commentary, published in response to the proposal, captures the popular indignation of a small town asked to pay a big bank during the Depression. The piece criticized the bondholders’ rapaciousness (“Let no one be deceived as to how they have developed their power and wealth simultaneously”) and argued for a fight in court: “As an alternative, the threat of the mailed fist through federal court procedure is presented. Opinion is rapidly changing in this country.”

In 1932, a new City Council was elected and set out to settle the bond validity question once and for all. The case made it to U.S. District Court, where the city found a sympathetic ally in Judge Yates Webb, an Asheville resident.

In his final ruling, Webb spoke openly about his desire to rule in favor of the city. As quoted in the Sept. 27, 1935, Asheville Citizen, he stated: “I have ransacked [legal libraries] in an effort to find some high authority [that] would enable me to relieve the City of Asheville of its liability. … I must confess to you that I have been unable to find it. On the contrary, I have been thoroughly convinced … that there is no legal way by which Asheville may be relieved of her obligations.”

The federal court ruling can be seen as a tribute to Gallatin Roberts. It noted that the bonds issued by the city had been used mainly to pay for significant, lasting infrastructure in Asheville — not for personal gain. The city did, and would continue to, receive revenue from the bonds. Therefore, it needed to pay back the bondholders. Though Roberts and Cathey ran up debt irresponsibly and inappropriately, in some ways those funds created a greater Asheville.

Payback

The conclusive Webb ruling brought about earnest negotiations from all sides and, in January 1936, a debt settlement agreement was announced in the Asheville Citizen. Asheville assumed all the debt of its districts and Buncombe County, which it would pay back in full with interest. A strict schedule of payments satisfied the bondholders and restored a sense of order to the Asheville economy. The settlement did not require Asheville to dramatically raise taxes, for example, and it prevented the city from defaulting. Most crucially to bondholders, the agreement made the debt legally incontrovertible.

The newly formed Sinking Fund Commission included prominent members of the business community tasked with executing the agreement. Announcements of its permanent secretary, Curtis Bynum, mentioned his degrees from the University of Chicago and the Sorbonne, multiple directorships and executive business roles. Bynum represented how the crisis in Asheville went from being perceived as an unmitigated disaster to a logical, character-building civic duty.

The next 40 years clicked by. “$5,265,347 in Public Bonds Retired Here,” proclaimed a June 22, 1941, news story in the Asheville Times. These headlines came around annually like clockwork. The debt was recorded on promissory notes. When the city retired debt, the bondholders would return the paper. Government and Sinking Fund members would then burn those notes in the city incinerator. One newspaper photo shows the city’s auditor, the chairman of the county Board of Commissioners and the mayor cremating retired debt instruments.

The debt agreement limited Asheville’s ability to fund development over the 40 years that followed its financial catastrophe. Whitehorn describes city spending from 1936 until the 1970s as having been largely focused on “getting rid of the albatross.” But, she continues, “the beauty of it is that we couldn’t do the things in urban renewal that so many cities did. We still did some things that were not great from the perspective of our community, but we didn’t tear down all the art deco buildings and replace them with malls. Because we didn’t have the money.”

In the end, Whitehorn explains, “We ended up keeping these boarded-up buildings we thought were eyesores. In reality, they were treasures.”

Reporter Doug Reed’s first beat when he began at the Asheville Citizen-Times was the municipal debt. He covered it voraciously, developing relationships with major players such as Curtis Bynum. Now in his late 80s, Reed still remembers Bynum speaking to him about the 1936 settlement agreement and how “not long after people grew ignorant.”

Past meets present

The facts of Asheville’s municipal debt calamity are convoluted and difficult to parse out. The crisis, however, continues to haunt Asheville’s institutional memory. When Whitehorn arrived at City Hall in 2013, municipal debt had a reputation as “a big scary thing. [Yet] in the municipal world, debt is seen as a much more reasonable way to pay for infrastructure.” Curious about the source of the anxiety, she learned about the municipal debt story and it began to make sense. “It gave me a lot of perspective on why people are so reticent about debt here.”

It also gave her a further appreciation for creative alternatives to taking on debt, she says. For example, Asheville’s entrepreneurs tend to develop existing real estate rather than build anew. “Instead of sprawl, you’re building up,” adds Whitehorn. The city also created financial incentives to encourage development in specific areas such as the River Arts District

This spring, City Council proposed a referendum for the November general election to authorize up to $74 million in general obligation bond borrowing. For Whitehorn (who stresses she is not allowed to advocate for or against the bonds, only educate), municipal debt is an innovative tool of development if used responsibly. She sees Asheville’s positive credit rating and its relatively low debt load as “this one shiny tool that everyone uses. Asheville’s keeping it very nice, shiny and lovely and not using it. And it’s the best tool. Like instead of using the screwdriver, using the power drill.”

Concerned citizens point to the past as a warning for the future. At a public debate in October, former City Council member Carl Mumpower said, “The world economy is teetering, and Asheville is about to do the same thing we did in the 1920s: Borrow money while the sun is shining and ignore very dark clouds on the horizon.” [See more about the debate in this issue of Xpress, in the article “GO or No-Go?”]

Asheville’s municipal debt crisis, though, may have been a singular event. Not only were the circumstances different in scale, but Asheville (like all municipalities in the state) must now obtain the approval of state regulators before creating new revenue streams — a procedure that some say is a direct result of the 1930s municipal crisis. Asheville’s government structure, and the world we live in, is more transparent now than it was in those days of tense check-signing scenes behind closed doors in City Hall.

However, if approved, these referendums could bring about a significant, if subtle, change for Asheville. Many cities have a rolling debt program, in which every few years old debt is retired and new debt is subsequently taken on, says Whitehorn. Due to the city’s first inability, then reluctance, to take on debt, Asheville doesn’t have this cycle in place. November’s election could mark the beginning of such a process. And while it’s easy to dismiss a comparison between the two eras, hindsight, which is always more accurate than prediction, presents a haunting view.

Despite the tragedy and hardship it imposed, Asheville’s debt crisis had some positive effects for the city over the long run. It saved the art deco buildings, now an important draw for the tourist economy. It unified Buncombe County and Asheville. It produced a culture of municipal problem-solving born out of financial constraints. Beneath those contributions, though, is the painful reckoning of Gallatin Roberts and other citizens who lost everything on Black Thursday.

“In Asheville,” Whitehorn says, “we wonder: Is the best way the way we did it last time? Maybe not.”

Excellent historical article. Thank you :-)

Yes, very interesting article however , writer failed to mention that the PAYBACK on this latest bond SCAM is $110 MILLION + !

Read the 10 reasons to Vote NO at http://www.AshevilleUnreported.com

we MUST defeat this heinous referendum!

Property speculator still fails to understand how mortgages work, film at 11.

Now that the Great Recession of 2008 is behind us and money is flowing, the City should be spending money to upgrade our infrastructure. However, the funds should be directed toward core needs such as crumbling sidewalks, decaying, leaking water lines, etc. Not spent on an $80million river front greenway. It would be similar to an individual finally getting a much needed job and spending the money on a new swimming pool versus fixing the leaky roof.

There is still plenty of “behind closed door” activity going on at City Hall to fulfill personal agendas with taxpayer money. Look at it this way…would you rather be remembered as the mayor who fixed the leaky pipes? Or, the mayor that created a lovely riverfront greenway? Everyone would love to see a new riverfront greenway. The problem is, it’s your money they are spending not theirs.

“would you rather be remembered as the mayor who fixed the leaky pipes?”

In case you hadn’t noticed the hundreds of stories about the Asheville water system and its possible fate — thanks Little Timmy Moffitt! — the mayor doesn’t fix leaky pipes. At least, not in the way you imply. The water department is funded by user fees.

“Not spent on an $80million river front greenway.”

It would be difficult to do that on a $32m bond unless the city were to take it to a casino. Your number is BS. The section of greenway considered under the infrastructure bond connects River Bend Park to the Azalea Road Rec Park ($3.6m) instead of having to build a sidewalk along that stretch of Swannanoa River Road. I think that’s a smart use of bond funding: the little park was the figleaf the city got from developers when the old Sayles Bleachery site was turned over to WalMart and the other big-box stores. It’s isolated, hard to access on foot, and deserves more use. At the same time, River Road needs safe pedestrian access from the mall to Oteen: it’s on a bus route where half the stops are on grass verges. It’s hardly a luxury.

Naturally, I would be against a debt, but we need greenways. Asheville is way behind Knoxville, Greenville and other cities. The economic benefits are enormous. People and businesses choose an area based on its amenities. That said, the Bent Creek Greenway should be the priority to connect South Asheville with Bent Creek Rec. Area and the rest of Asheville. I would like one day for Asheville’s greenways to connect to SC’s Swamp Rabbit and the Virginia Creeper Trail.

But did “Knoxville, Greenville and other cities” neglect THEIR infrastructure to create pretty walking paths?

If they did not, then we should follow their example and set reasonable priorities.

If they did, then you are suggesting that we should be just as foolish as everyone else. Very “progressive” of you.

LOL, not only did the powers at be neglect their responsibilities, they added more fees to keep the cash cow going for their friends. We support the rich, the elitist, and the cronies here. Nothing more and nothing less. Period.

What if someone today has one of the 1920s bond anticipation notes that was never cashed In?