Decades after the furor over a Swannanoa weapons plant introduced many residents to the term “Superfund site,” the focus is shifting toward potential future uses for a portion of the Chemtronics property. Remediation efforts have gradually reduced contamination levels, and an upcoming decision by the Environmental Protection Agency, due out in September, is seen as a starting point for proposals to turn a portion of the site into something that might benefit the community.

Apart from some warning signs, there’s little indication that a Superfund site slumbers in the midst of a community in transition. Residential subdivisions, small farms and several businesses butt right up against the property line, in the shadow of the Black Mountains. But from the early 1950s until the 1990s, the facility produced chemicals, propellants, explosives and, at one time, top-secret chemical weapons. Many toxic byproducts were disposed of on the 1,027-acre site, releasing dangerous pollutants into the groundwater and soil (see sidebar, “Chemtronics timeline”).

In 1982, the EPA included Chemtronics in the first National Priorities List of sites posing substantial risk to their surrounding communities. Since then, extensive containment and remediation efforts financed by the several companies involved and overseen by EPA officials have gradually contained and reduced the threat posed by those wastes, which are concentrated in a small portion of the property. No off-site contamination has been found.

In September, the EPA will issue a new “record of decision” for the site, officially spelling out the future remediation strategy and what uses will be allowed. Anticipating this, elected officials, EPA representatives and area residents are weighing in with their concerns and ideas for transforming the property.

Economic development

The site’s post-World War II history reflects both Cold War tensions and differing visions of community development.

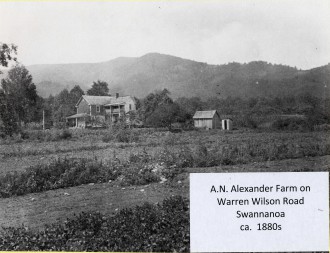

First settled in the 1790s by one A.N. Alexander, the property — tucked away in a remote corner of the Swannanoa Valley at the end of Old Bee Tree Road — remained in the family until the early 1950s, says Swannanoa resident Bill Alexander, a direct descendant.

“Charles Alexander had a construction company at the time,” he explains. “He figured selling the land would be a great investment for his business,” and it was — he got the contract to build the plant.

At the time, the coming of the Oerlikon Tool & Arms Corp. of America, whose parent company was based in Switzerland, was hailed as a great step in the community’s development. A 1951 article in the Black Mountain News said the property’s transformation “has been so complete that it’s hard to imagine the era before electricity.”

In a June 1952 article, Time magazine called the construction of the $3.5 million plant a victory in America’s “snail-paced arms buildup.” According to the article, 4,000 workers would eventually be hired to produce air-to-ground rockets and 30 mm automatic cannons.

When the first workers arrived, Alexander recalls, “They were mostly outsiders, many from Germany. I still knew all the trails back there, and I’d walk through the property with my friends.”

In 1959, Oerlikon sold the plant to the Celanese Corp., which in turn sold it to Northrop Carolina Inc. in 1965. Chemtronics, now a subsidiary of Halliburton, took possession in 1971.

Cold War secrets

Information about plant operations in the early days is scarce. In a 1983 deposition for the EPA, Naman Radford, who handled materials disposal for both Northrop and Chemtronics from 1965-71, said Northrop management would “tell you whatever went on in here, don’t tell nobody. They said it was government work and highly confidential.”

But employee depositions reveal that in addition to rocket engines, a vast array of chemicals and explosives was produced on-site, including CS (tear gas), Mark 24 flares and the top-secret BZ, a powerful hallucinogen meant to be used to subdue enemy populations. Many employees had minimal knowledge of the chemicals they were dealing with, and worker safety standards were crude at best. In 1965, a fire broke out in one of the buildings and threatened to ignite 3,000 pounds of explosives. Neighbors within a mile of the plant were evacuated.

Disposal methods read like an environmental horror story: drums of BZ and CS buried on-site; liquid chemicals dumped down a drain feeding into a nearby stream; explosives incinerated in what the EPA calls the “acid pit area.” On several occasions, hazardous materials were trucked off-site to nearby landfills.

In a 1983 deposition, former Buncombe County landfill operator Tony Plemmons recalled being exposed to CS powder while burying material dumped by Northrop employees. “It like to smothered me to death and blinded me. It all just boiled right up in my face and up my pant legs. I didn’t even know what it was.”

The secrecy surrounding the plant also sparked many rumors, notes Jon Bornholm, remedial project manager for the EPA’s Region 4. For example, rockets fired during testing were said to have sometimes ended up escaping the property and “going over the mountain.” But Bornholm dismisses those reports “and all sorts of other stuff” as legends, adding, “Information prior to 1970 is hard to know for certain.”

Three off-site areas were part of the EPA’s original 1980s investigation, he explains. “This included the current Ingles location, the Walnut Cove area and the Tandy Corp. property. No chemicals were found at these sites that could be linked to Chemtronics.”

Vicki Collins, a retired Warren Wilson College chemistry professor who’s studied the site extensively and currently serves on the Swannanoa Superfund Community Advisory Group, says, “There have been lots of colorful rumors about Chemtronics, a few of which are probably true.” And while off-site dumping is certainly a possibility, she notes, “The general procedure was just to dump the stuff out on the ground nearby. My opinion is that they just wouldn’t bother to load the stuff up and take it out to hide.”

Containing the mess

Matters came to a head in 1979, when a neighboring resident complained to state officials about foul odors emanating from the site. Investigations revealed possible groundwater and soil contamination, and in 1980, the state Department of Environment and Natural Resources ordered the company to stop dumping and incinerating wastes in the open pits that had been dug, filled and redug for at least a decade. Further soil and groundwater tests identified a host of toxic chemicals at several disposal sites.

Two years later, the property was designated as a Superfund site and, over the next decade, contractors hired by the designated “potentially responsible parties” (Northrop, Celanese and Chemtronics) conducted tests to determine the location and extent of the contamination. Some residents, Bornholm noted in 1988, likened those companies’ involvement to “letting the fox guard the henhouse.”

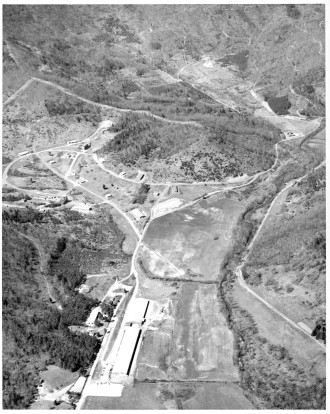

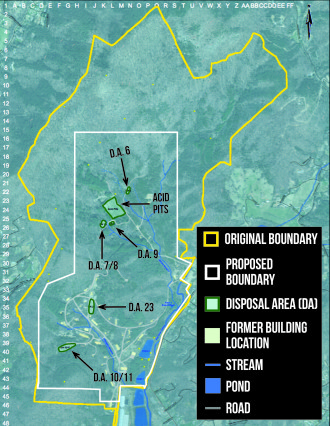

The EPA divided the property into two main areas: the “front valley,” where most manufacturing activity took place and wastes were dumped, and the “back valley,” where hazardous materials were incinerated. The lowland disposal areas cover less than 10 acres; about half the site consists of rugged upland terrain.

“The major pollutants are chlorinated hydrocarbons like TCE — the chemical contaminating the CTS site,” says Collins. CTS, a Superfund site in South Asheville, formerly housed an electroplating facility (see “Fail-Safe?” July 11, 2007, Xpress). At both sites, these chemicals “were used as solvents and cleaning agents. They sink into pools deep in the groundwater and very slowly dissolve in small amounts,” Collins explains. Small amounts of heavy metals, explosives residues, perchlorate (a water-soluble component of rocket fuel), volatile organic compounds and decomposed BZ byproducts were also found in soils on the Chemtronics property.

Meanwhile, as public awareness of the extent of the contamination grew, community members were outraged. Residents and elected officials alike expressed concerns about the secrecy, potential hazards, the EPA’s alleged lack of transparency and a proposal to burn all contaminants in a giant incinerator on-site (which was later rejected).

The long road to remediation

In 1988, the EPA settled on a containment strategy. Each of the six disposal areas was capped with an impermeable cover made of clay and concrete, topped with several feet of soil to encourage vegetation growth. They were fenced to keep people out and tracked via monitoring wells. “The caps and fences are regularly maintained, and groundwater around each disposal area has been monitored at least annually since the early 1990s,” says Stu Ryman of Altamont Environmental, Inc., an Asheville consulting firm hired in 2000 to oversee evaluation and remediation efforts.

Beginning in 1993, each valley had an extraction system installed. “Groundwater was pumped over screens where air evaporated the solvents, and cleaner water was sent to the MSD treatment plant,” Collins explains. But the pumps are prone to clogging, and progress was slow.

Meanwhile, as public awareness of the situation grew, “Chemtronics became an attractive nuisance,” notes Bornholm. Manufacturing operations ceased in 1994, and all remaining structures not essential to remediation efforts were torn down between 2004 and 2006.

Making headway

In December 2012, after a three-year investigation that analyzed 541 soil samples and water samples from 175 monitoring wells on the property, Altamont Environmental released its initial findings and EPA representatives met with nearby residents to discuss forming a community advisory group. The final Remedial Investigation report, released late last year, found “no unacceptable risks for human health,” apart from a few hypothetical scenarios concerning potential future water usage and excavation efforts. There were also said to be no adverse effects on wildlife, although three soil areas and 11 groundwater areas were said to warrant further investigation. Overall, on-site exposure risk for humans was deemed “relatively low.”

And though several of the monitoring wells deep within the property continue to show contamination at hundreds of times the federal limits for drinking water, “These levels drop as the water moves downgradient,” says Collins. “All wells and surface waters near the property boundaries meet drinking water standards, [and] Bee Tree Creek and wells in surrounding properties are clean.”

New approach

Altamont also began exploring alternative remediation methods. In 2009, the firm launched a pilot study that involved introducing an emulsion of vegetable oil to promote bacteria growth. This approach, Ryman explains, “encourages bacteria to … convert the contaminants to nontoxic end products.”

The early results have been “very encouraging,” says Collins, with contaminant levels in the back valley down about 90 percent within the first few months. Results of the pilot study will be evaluated in the forthcoming EPA report.

Nonetheless, the federal agency estimates that remediation efforts will continue for at least the next couple of decades, particularly in the front valley. “It would be many years before the owners would contemplate any use for the [valley] property,” notes Collins. “This is a big site with big problems, and it’s unreasonable to expect cleanup to happen in a few years.”

Evolving visions

In 2013, the community advisory group was formed to officially represent the residents. “We serve as the voice of the community in this process,” says founding member Amy Knisley, a professor of environmental law and policy at Warren Wilson. “We’re the intersecting point between the EPA, Altamont and the community.”

Besides disseminating information and fielding questions through its website, the group holds quarterly meetings at the Bee Tree Fire Department at which speakers report on progress and address community concerns. Besides representatives of Altamont and the EPA, “Politicians like Ellen Frost, Mike Fryar and John Ager have made occasional appearances,” says co-founder Grant Millin, a local management consultant. “Only a proper assessment from a collaboration of experts and citizens can determine the risks.”

One proposal being floated calls for dramatically reducing the size of the Superfund site. Roughly 530 acres of steeper terrain ― where no contaminants have been found ― would be exempted from Superfund restrictions and placed under a conservation easement through the Southern Appalachian Highlands Conservancy.

“It’s something we’ve wanted to work on since the ’90s,” says Michelle Pugliese, the nonprofit’s land protection director. “Now we’re trying to gear up and get more involved in talking to the property owners about doing the conservation easement. They’re very much on board with that.”

Both EPA officials and the advisory group have publicly expressed support for the idea. And state Rep. John Ager, whose 115th District includes the site, says, “As a longtime land preservationist, I have promoted this solution, and I believe we have consensus.”

Some residents, however, have expressed concerns. “If it’s removed from that legal designation, then it comes out from under the watchful eye of the EPA,” explains Knisley, who’d like an easement to include limited public access to the property. “It doesn’t have to be unfettered: It could be twice a year wildlife walks, and our ecology faculty could help lead them,” she points out.

To date, though, Chemtronics ownership hasn’t had much to say about the idea, notes Knisley. “I understand that reservation,” she continues, “but I think it can be dealt with. I think it’s in everybody’s long-range benefit.”

Pugliese, meanwhile, says the conservancy has tried to allay residents’ concerns by attending advisory group meetings and explaining how a conservation easement works. “I think it’s been an educational process for everyone involved,” she says. “The public access part is a very complicated issue. Chemtronics really just wants to make sure it’s safe.”

Attorney Robert Fox, who represents Chemtronics, declined to comment, saying he doesn’t discuss ongoing matters.

Formal discussions concerning an easement could get underway later this year, Pugliese reports. “This is an exciting project for me, because it’s very innovative. It’s the first time the conservancy has ever worked on anything connected with a Superfund site. There’s all of these steps, regulatory and legal, that make the time frame a little hard to predict.”

Life after remediation

Millin, whose professional work focuses on sustainability issues, hopes that both Chemtronics and government officials will eventually consider utilizing the site for the community’s benefit. He points to other revamped former Superfund sites, such as the South Carolina Aquarium in Charleston, or Charlotte’s ReVenture Park, a 667-acre Superfund site along the Catawba River that was transformed into the nation’s largest eco-industrial park in 2012.

Millin believes the Chemtronics property could serve a similar purpose. As a first step in shifting the thinking, he’d like to see a name change. “I want everyone to start calling it simply ‘180 Old Bee Tree Road’ in order to help visualize a new direction,” he explains.

“If the site can have some cool reuse like a sustainability think tank on it, that means it’s been cleaned up pretty well.” But so far, he continues, the property owners have been reluctant to consider that possibility.

The EPA has argued against allowing future residential development, and Chemtronics and its parent companies have yet to express any long-term vision for the contaminated portions of the site.

The EPA’s forthcoming Record of Decision, notes Knisley, will “make it clear what the rules of the game are, so the [companies] know that as long as they work in accordance with the law, they won’t get in trouble.” It will be posted on the Federal Register with a 60-day public comment period, and the advisory group will hold at least one major meeting where the agency presents its findings.

“This is a critical juncture, because the 2016 record of decision will stand for a long time,” says Millin.

Lessons learned

In Buncombe County alone, there are dozens of inactive hazardous waste sites that could pose risks to neighboring residents (see “Hidden Hazards,” Jan. 11, 2011 Xpress). Meanwhile, at the CTS site, residents whose wells were tainted have faced major health problems and, decades later, are still waiting for the contamination to be adequately addressed.

Against that backdrop, the Chemtronics site presents a somewhat different picture.

The questions about Chemtronics, says Millin, “aren’t more important than the CTS problems, but the Chemtronics site should not be ignored by the people of Buncombe. They deserve to see all the points of interest laid out properly.”

For his part, Ager stresses that “Trust and credibility must be built up over time” between the community, the EPA and the property owners. He calls for continued transparency in any future decisions, en route to some form of regulated public use that “would make the site an asset to the community rather than a liability.”

To that end, Millin urges concerned residents to attend advisory group meetings and get involved. “Any Buncombe citizen is welcome,” he says. Rather than working individually, Millin maintains, it’s “best to speak your mind as a team and ask the responsible parties for a better set of options.”

Collins, who’s been involved with the site for decades, takes the long view. “It’s easy to forget that Superfund was not in existence until 1980,” she points out. “A lot of the dumping occurred long before that, when there was no real concern about the environment, so there just weren’t any records. The secrecy probably exacerbated the public outrage in the mid-’80s. … It’s easy to get frightened of the unknown, and there had been some very nasty stuff there.”

The site, she continues, “is a difficult and complicated one to explain, and federal and state regulations can seem very confusing. EPA is charged with preventing risk to people and the environment, not simply with totally removing contamination.”

Asked what might be learned from the Chemtronics experience, Collins said: “First, the site manager is very important. … Running a meeting of worried citizens is a very difficult task for an engineer like [Bornholm], but he always showed patience. Second, it definitely helps when the responsible parties cooperate. … Those big corporations can certainly afford the cleanup. Third, patience is important on all sides. The pace of EPA bureaucracy can seem glacial, and it just takes a long time to clean up a big mess like this one. Fourth, science is getting better: The new cleanup process sounds quite promising at this point. We’ve come a long way since 1980!”

Pugliese, too, sounds a positive note. Despite the many remaining questions, she believes the property could become a good example of fruitful collaboration. “I think you’re taking a very unfortunate situation ― no one wants to see this beautiful landscape contaminated ― and turning that around into something positive,” she says. “It’s really an example of how we can take lemons and make lemonade.”

Collins, though, also notes the fluctuating nature of community involvement with the site.

“Public attention did die down as cleanup proceeded in the ’90s. … I think the community mostly just forgot. I remember an important meeting in 2003 which was attended by fewer than 10 local residents.” And in 2012, when the EPA “got serious about inviting the community to set up an advisory group, the former pattern repeated itself: a big meeting with lots of questions and some anger directed at Bornholm, followed by lots of community meetings to set up the advisory group, with steadily declining participation. Now we often have less than 20 people show up.”

And looking ahead, Collins adds a cautionary note: “I think people should think very carefully when presidential candidates talk about abolishing the EPA. Dealing with the bureaucracy can be trying, but think of what the site would be like now if the EPA weren’t there!”

To learn more about the Chemtronics site, the Superfund process and possibilities for community involvement, contact the advisory group at swannanoasuperfund@gmail.com.

Keep in mind that an innovative, sustainability-oriented economic development strategy for the lower part of the 180 Old Bee Tree Road property does not exclude the need or possibility of a conservation easement in the upper, more or less undeveloped part of the land.

These massive corporations behind this property, Halliburton Company, Northrop Grumman, and Celanese Corporation, can afford to do an excellent job with the lower heavily contaminated part of the land. It is really about whether enough Asheville and Buncombe citizens and elected officials feel this unique and extraordinarily large property matters for our future.

My guess is that it is actually possible to convince the property owners that a Ready for Reuse certification for the lower, previously developed part of the land is best for Buncombe County. This case is like a lot of things, we won’t know if we ignore this opportunity.

https://www.epa.gov/superfund-redevelopment-initiative

Do all the costs of this, along with the costs of thousands of similar sites, appear in the calculus of military spending or are they yet more indirect subsidies to the Pentagon and death merchants?

Hey vrede,

Thanks for reading and commenting! I’m a little confused by your question. If you mean the cost of the remediation and containment efforts, that is the responsibility of the PRPs (Chemtronics, Celanese and Northrop). They are responsible for paying for and conducting all the work done on the site, with the EPA overseeing and approving/amending their proposals and plans.

I do know that the army was involved in removing some of the exposed BZ and CS drums from the property in the 1980s. The facility was also a UN Weapons Convention site during active operation, so there may have been some sort of military involvement or oversight in regards to that, though I can say what that would have entailed. Grant Millin or others more closely involved with the site may have more info on that.

I suspect that not all eventual costs to the public will be covered by billing for remediation and containment efforts. Regardless, my post was meant to be about how our war making and war industry costs us far more than just the massive amount seen in our war budget.

Thanks for the informative article.

Thank you for reading, vrede! I appreciate you providing your thoughts on this. You raise some good points. My understanding is that all direct remediation and containment costs are the responsibility of the PRPs under Superfund/CERCLA legislation, as laid out here:

https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-comprehensive-environmental-response-compensation-and-liability-act

However, there are undoubtedly costs to any community that may not fall under CERCLA perimeters. These costs are often hard to qualify, and from my experience researching these sites, a good amount of controversy exists regarding what EPa and the PRPs are responsible for providing and covering on a given site. I’m not an authority on the legal aspects of this, though, and can’t speak definitively about this.

I agree that the military-industrial complex in our country has contributed to a lot of unforeseen costs to the populace, many of which we’re probably not aware of. There’s a reason that a five-star general and former president like Dwight Eisenhower would publicly warn us about allowing war to become a profitable business.

Halliburton operated on the property, as a commercial, and military chemical and explosives producer under the cover name of Accurate Arms. During the Iran Contra scandal of 1980s. As a CERCLA Superfund, (signed into law 12/11/80 by Jimmy Carter). Halliburton was named on the very first highest ranking list; (HRL) printed in 1981. Scoring above 28.5, on the 0-100 scale. This Halliburton site was then placed on the very first national priority list (NPL) printed in 1982 in 12/1982. It’s production served Iran Contra and MIC, suppliers such as Delfasco, MTD, MECO, Newport News in Greeneville, Tn. It made, but was not limited to; core explosives for MIC products such as Missiles and Bombs. Containing such explosives as HMX, HNS, PETN, RDX, TNT et al..

During the Iran Contra investigations. Dick Cheney was onsite. After, interviews with employees, they moved production, during the Iran Contra scandal to Mc Elwin, Tn.. The waste was dumped both off and onsite legally and illegally. Halliburton and Dick Cheney then began in Mc Elwin, Tn., first as Accurate Arms, and now as Accurate Energy Systems LLC. Explosive accidents, in addition to its toxic releases have genetical altered or killed those of its employment and those of its toxic interaction in public record. As before the move, it now produces for such industries as the commercial Oil and Gas Exploration, et al.. Which use Halliburton’s explosives as HMX, PBX, RDX, C-4. Companies such as George Bush’s Zapata; Houston, Tx. and Federal Judge Leon Jordan employer Frontier Oil of Colorado, headed in Houston and those in Kuwait and Iraq were their customers. Federal Judge Leon Jordan, was nominated by Reagan/Bush to the Eastern District of Tennessee, during the Iran Contra scandal in 1988.

There were other Iran Contra period nominated Federal Judges to same district; Thomas Hull 1983, James Jarvis 1984. Then to continue the line of association to Reagan/Bush/Lamar Alexander. George Bush Jr would replace Hull with J. Ronnie Greer in 2003. All are or were one or more of the following: co Oil, co Banking, co Military, past co practice, partners and associates. Or they were associated legal officers, campaign managers, special assistants, Judge Advocate General lawyers, legal consuls, law school, military, et al. to Reagan/Bush, Lamar Alexander, Howard Baker, Robin Beard, et al.. Their practices and/or nominations are associated to the State Judge Nominations of Lamar Alexander to the Eastern District of Tennessee. To the cases associated to the withheld Superfunds of Iran Contra, the Iraq War; of illegally used munitions and federal currency, in Greeneville, Tn.. The currency found in Iran during Iran Contra, in the Iraq War, in Saddam Hussein’s cache, et al.

Their firms, their practices, their jurisdictions would became implicated in drug smuggling. They would be convicted. The same source used by the CIA, Reagan/Bush Administration, from Columbia, to the U.S., to their Greeneville, Tn.. Used to fund the munitions and monetary requirements. Ann Gorsuch; the first head of the EPA, under Ronald Reagan/George Bush. Refused during; Sewer Gate, Lawyer Gate, and beginning Iran Contra investigations in Congress. To turn over the Superfund lists. Which led to at least 10 of the Iran Contra, production sites located in Greeneville, Tn.. , and the Asheville, Swananoa, area in N.C.. Reagan/Bush et al., instructed Anne Gorsuch to take Presidential Executive Privilege, to prevent discoveries, in 12/82, before the Congress. Because of that; she became the first agency head in history to be held in contempt. She resigned in 3/83, before charges and trial.

(Reagan/Bush/EPA/Anne Gorsuch/ et al.) at that time illegally withheld their treason. They knew they corrupted the Boland Amendment, committed treason by supplying terrorist countries, and caused the death and illness associated to production. Reagan/Bush/Lamar Alexander simultaneously used their politically nominated heads at cabinet, and agency levels. For the discovery of the magnitude of impact committed by their covert sites of treason. #1 for content: They used the (EPA, Environmental Protection Agency), (TDEC, Tennessee Department of Environmental Conservation), (DSWM, Department of Solid Waste Management), ( EPA, CERCLA, Superfund). #2 for volume by the (USHC United States Highway Commission), (USDOT United States Department of Transportation), (USGS United States Geological Survey), (TNDOT Tennessee Department of Transportation), (USDOI United States Department of Interior).

The outcome, was extreme impact, to most of the entire Eastern Mississippi Watershed. A spread in lifespan; is as great as 27 years along the range.

Of the eleven Judges known, who were involved in 16 known cases related cases transpiring over the last forty years of sites involvement. In cases of real estate, contamination, property, bankruptcy, mortality et al.. Containing more than 150 law firms and 400 entrants that invested more than ten thousand years of combined effort. Who were paid, and lost billions of dollars. None, have ever entered these contamination records of these sites involvement into case record. Nor the material, death and illness loss they caused.

I worked for chemtronics in early 70s. just manual labor. article is spot on in terms of training. never trucked any waste off site. just dumped in ponds on property. the colors, smells and reactions when the new waste and residual waste combined _ I will never forget

Mostly correct content. Lineage of the property is incorrect. A. N, Alexander was NOT a settler from the 1700’s, he was grandson of those settlers. He DID own much of the Bee Tree Valley – and many other properties, but that was from the mid 1800’s until 1927 or so.. Charles Alexander did not get a contract to build this plant. He was the son of A.N Alexander, and sold the property to Oerliken. His son and grandson (Perry M. Alexander Sr and Jr were in the construction business, but only for grading – not construction of buildings. They are all pictured in another AC-T article, showing the grading beginning in front of the home place.

To the mountainx.com admin, Your posts are always well thought out.