There’s no escaping the public health message that’s reverberating across North Carolina. Practice the three W’s: Wear a face covering. Wait 6 feet apart. Wash your hands. But there are significant differences in how counties in the western region are delivering it.

Mandy Cohen, the state’s secretary of health and human services, reiterates that advice every time she steps to the lectern in Raleigh’s COVID-19 Emergency Operations Center. Stacie Saunders, Buncombe County’s public health director, echoes that counsel when she shares updates with residents and elected officials.

Mark Jaben, Haywood County’s medical director, tries to drive home the message during his signature coronavirus updates, which are filmed in his house. The catchphrase appears in the weekly press releases sent out by the Henderson County Department of Public Health, and it’s all over radio ads, billboards and social media feeds.

It’s a communications strategy that appeals to loyalty and respect, says Gene Matthews, a senior investigator at the North Carolina Institute for Public Health who studies the ways that framing a health message can affect how it’s received by people holding different ideologies. But as local health officials try to find the best way to get important health information out to Western North Carolina residents, they face an uphill battle: COVID-19 cases are rising nationally, misinformation runs rampant, and public health guidelines are the focus of fierce partisan debates.

In North Carolina, local health departments are required to report COVID-19 cases, outbreaks and diagnostic test results to the state Department of Health and Human Services, says HHS spokesperson Amy Adams Ellis. But they’re not required to publicly post or share that data, leaving it up to each local entity to decide if, when and how to do so.

And while WNC counties are making vital pandemic-related information public, they’re not all taking the same approach. “It’s been an evolution,” says Haywood County Emergency Management spokesperson Allison Richmond. “Nobody knew how to do this before.”

Keeping it fresh

Before Matthews took his current position with the Institute for Public Health, he spent 25 years as the chief legal adviser to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, providing guidance on the AIDS epidemic and the 9/11 and anthrax attacks. In such emergencies, he explains, the textbook strategy is to let public health experts speak directly to the people without any political slant.

But the public health messaging around COVID-19 has become weaponized and politicized by leaders on both the political left and right, leaving many people skeptical of any information about the pandemic that’s coming from a political figure, says Matthews. Against that backdrop, he continues, the most trusted spokesperson tends to be the local county health director.

Even so, notes K. “Vish” Viswanath, a professor and director of the applied risk communication program at Harvard University’s School of Public Health, any messaging coming from a credible source must be clear. But the rapidly changing science concerning the virus makes clear messaging more difficult, he points out, citing health officials’ reversal of their initial advice on face coverings after further research showed that cloth masks could help limit COVID-19’s spread.

Misinformation amplified by political leaders and disinformation shared widely via social media pose additional challenges for public health officials, continues Viswanath. And then there’s COVID-19 fatigue: At this point, people are just plain tired of hearing about the disease and the endlessly repeated public health messaging.

“The question becomes, how do we keep it fresh?” Viswanath explains. “I don’t think there’s an easy answer. You have to be forgiving, you have to be understanding that people are tired — and somehow, you have to motivate them to stick with these messages and comply with them.”

Accessible, accurate information

From the beginning, Buncombe County officials wanted the community to know that they were taking the coronavirus seriously. They also knew that a “one size fits all” communications strategy wouldn’t work, says Health and Human Services spokesperson Stacey Wood. Accordingly, they’ve tried to provide information in various ways that county residents can connect with, she says.

Those strategies have included daily dashboard updates, press conferences, a series of “Let’s talk COVID” panel discussions with community leaders, and weekly press releases. Officials discontinued the press conferences at the end of September; bimonthly updates are now shared during Buncombe County Board of Commissioners meetings.

Accessibility across cultures is also a priority, notes Wood: Community updates are translated into Spanish and American Sign Language, and until recently, the county’s dashboard included a translation feature offering six languages in addition to English. On Oct. 26, Buncombe County discontinued updating its dashboard, redirecting site visitors to the state HHS dashboard instead.

Federal law prohibits the release of personally identifiable health information, such as a patient’s prior medical history or treatment details. But within those limits, “There was never a question that we wouldn’t be as transparent as possible,” County Manager Avril Pinder wrote in an email to Xpress. “At Buncombe County, we will always grow and adapt and get better, but that’s something that every government agency should commit to the community it has the privilege of serving.”

Doubling down on dashboards

In lieu of flashy press conferences, Henderson County’s communications strategy focuses on its COVID-19 dashboard, spokesperson Andrew Mundhenk explains. Back in March, Henderson County was the first regional entity to create a dashboard after the first COVID-19 cases were reported, he says. It now includes a running tally of cases at long-term care facilities, a count of recovered patients and a heat map displaying cases by ZIP code.

But the county’s dashboard pioneering didn’t end there. In early October, the Henderson County Public Schools became the first school system in the region to launch a COVID-19 dashboard tracking all positive cases traced to a school setting. The Haywood, Jackson, Rutherford and Swain County districts have since followed suit.

When the Henderson County school system announced in September that students would resume their studies via a hybrid model including both in-person and virtual classes, the district committed to notifying families whenever a school-related COVID-19 case was confirmed, spokesperson Molly McGowan-Gorsuch explains. Daily updates to a public dashboard were deemed the most efficient way to share pertinent data.

“Our district and schools have worked to provide transparency about our COVID-19 response to keep the public informed; respect the concerns and anxieties our staff, parents and guardians are facing; and try to provide them with the most helpful information they can use to make the best possible decisions for their families in an ever-evolving situation,” she says. “Being transparent also allows us to address misinformation before rumors cause unnecessary alarm.”

Unlike other WNC health departments, notes Mundhenk, Henderson County’s lacks direct access to social media channels, which limits the reach of its messaging. At the end of October, Henderson County Health Director Steve Smith began writing a weekly column, “Our Community and COVID-19: The Way Forward,” to “provide additional focus on the human element of the data and trends that we see,” Mundhenk said.

“We’re learning as we go,” says Mundhenk. “We’re taking it day by day and seeing what people are interested in and what data points people want.”

Simply put

In Haywood County, the plan thus far has been to simplify and personalize the message. At first, the communications team flooded the health department’s social media channels with guidelines and resources from the state HHS, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the World Health Organization and the White House. “That was our strategy: not to reinvent the wheel but to make sure we were sharing consistent, good information,” says Richmond.

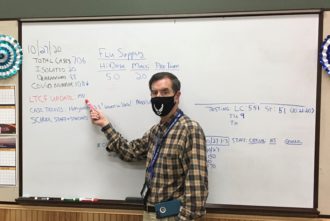

Weekly updates now come in both press release and video formats, headlined by Jaben’s personal calls for residents to take COVID-19 seriously. Unlike other WNC health departments, Haywood’s highlights patterns identified by contact tracing to show how the coronavirus spreads through the community.

“We thought if people understood some of the common ways it was being spread, they might know which situations they should avoid, like eating lunch with co-workers without wearing a mask,” Richmond explains. Other common flashpoints include parties, travel and failure to wear masks consistently.

But community members are tired of constant COVID-19 warnings. On Oct. 27, nearly 100 Waynesville residents packed a town board meeting to protest a proposed local mask mandate, sparking a back-and-forth about the importance of public health precautions. The COVID-19 response team is adjusting its messaging accordingly, Richmond says, with an increased focus on encouraging residents to do their part to protect neighbors, community members and friends, instead of “ramming orders down people’s throats.”

The best information-sharing practices aren’t developed in silos, she notes. Haywood is one of five North Carolina counties participating in a study run by Duke University’s Center for Advanced Hindsight and the NC State College of Design to improve local COVID-19 messaging using behavioral science. The pilot study is focusing on communication about masks, social distancing, vaccinations and misinformation, research assistant Dan Rosica reports.

Preliminary findings show that statistic-heavy COVID-19 messaging coming from the state government, or messages from state authorities that are disseminated by county officials, are generally less effective than those delivered by a respected local leader, he says.

Regardless of the method, Viswanath sees transparency as critical to ending the pandemic. “We know what works: When someone goes out and says what they know, what they don’t know and what they are trying to find out,” he explains. “If people see that honesty, it lends a lot of credibility to the messenger. And that’s when people start complying.”

PULL QUOTE

“It’s been an evolution. Nobody knew how to do this before.”

— Allison Richmond, Haywood County Health and Human Services

Transylvania county is doing an awesome job keeping people informed via social media.