In an April 6, 1960, meeting with federal highway officials, President Dwight Eisenhower, for whom the modern interstate system is named, famously told his assembled staff that he opposed “running interstate routes through the congested parts of the cities,” according to notes taken by Gen. John Bragdon.

Nearly 60 years later, Eisenhower’s reservations have proved prophetic for the city of Asheville. Since 1989, the I-26 Connector project has been an albatross that city officials, the state Department of Transportation and residents can’t seem to shake.

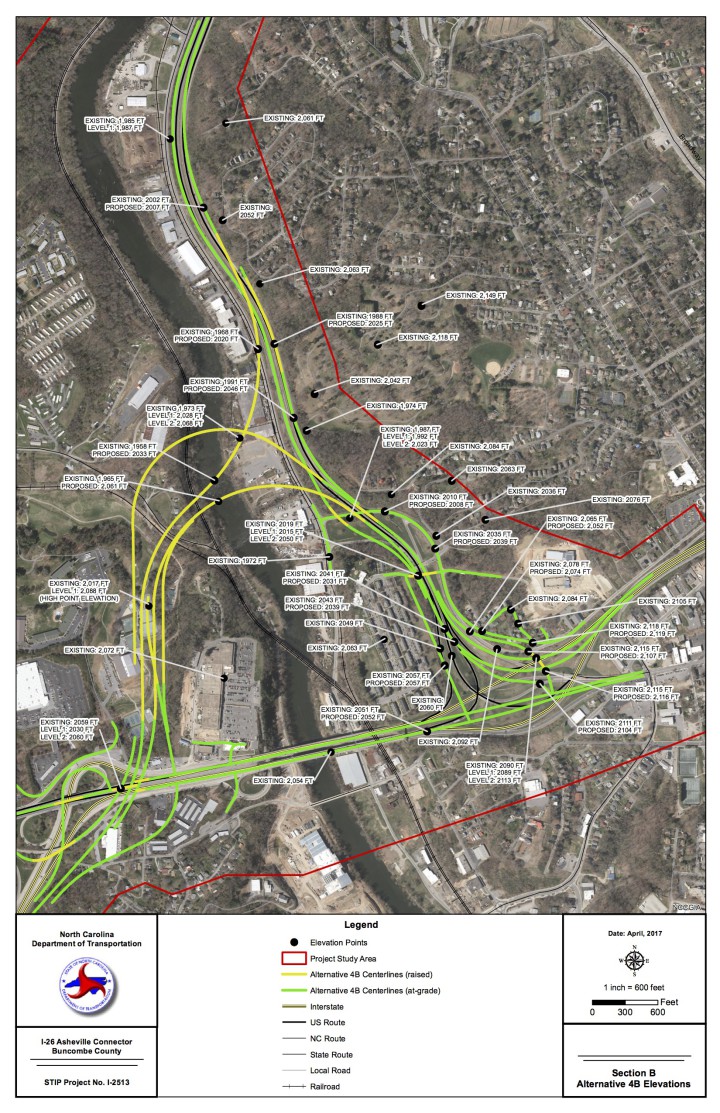

When the DOT finally decided on a design for Section B of the Connector project in 2015, many stakeholders thought they saw light at the end of a very long tunnel. Other residents, however, see serious flaws in Alternative 4B, questioning whether the project’s long-term benefits will justify the sacrifices their neighborhoods must make to see it completed.

Great expectations

Standing in an open lot adjacent to the Salvage Station on Riverside Drive, it’s hard to conceive of the changes the connector will bring to the surrounding landscape.

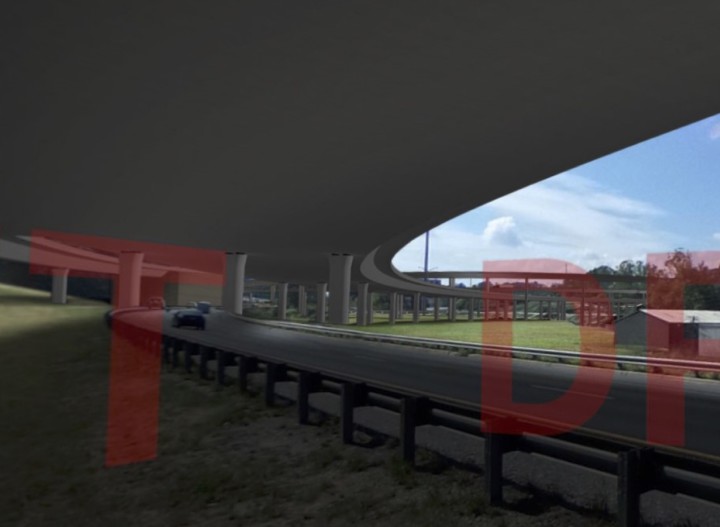

“How tall do you think that is? Maybe 10 feet?” asks Montford resident Suzanne Devane, pointing to an Asplundh Tree Expert Co. truck parked nearby. She and Lael Gray, members of the Don’t Wreck Asheville Coalition, stare overhead at a clear spring sky. “Now imagine 10 of those things stacked on top of each other. That’s what we’re going to have.”

Since moving to Montford in 2015, Devane — a communications specialist who’s worked with transportation engineering firms in Chicago — has spoken out against the DOT’s adaptation of the Asheville Design Center’s 2008 proposal. “It looks beautiful — who would disagree with that?” Devane says about the nonprofit’s original plan. “The problem is, we’re not seeing it.”

In theory, Alternative 4B does offer some significant improvements: diverting interstate traffic north from the Bowen Bridge, which leaves Patton Avenue to local drivers; greatly reduced impacts on West Asheville neighborhoods, compared with previous designs; a smoother transition between interstates 240 and 26, as opposed to the current frantic scramble across multiple lanes.

For these reasons, Alternative 4B has been widely viewed as the best solution to concerns raised by the Community Coordinating Committee (a coalition of Asheville residents and other stakeholders) in the early 2000s — and a win for the city in its efforts to influence the DOT’s elaborate and costly plans.

Conflicting priorities

But the way the project is actually shaping up, argues Don’t Wreck Asheville, is starkly different from the package the community was sold. From incursions into the Montford and Hill Street neighborhoods, to interchanges the equivalent of 10 lanes or more, and bridges rising 100 feet over the river on “horizontal curves,” the grassroots coalition asserts, 4B will drastically disrupt riverside commerce and life. The Design Center had originally envisioned a double-decker bridge that would carry both I-26 and I-240 traffic, reducing the highway’s footprint and, therefore, the impact on the surrounding area.

“We’re trying to make the riverfront really pedestrian- and bike-friendly, and to develop the areas that have that potential,” says Gray. “Why would we then put these massive highway structures in the middle of all of that opportunity and current activity?”

Devane, meanwhile, brandishes an architectural rendering of the very area we’re standing in. Pillars line Riverside Drive on either side, and a massive overpass looms overhead. The bridges, she says, are unattractive, and the horizontal curve design proposed for I-240 poses significant safety hazards. According to the Federal Highway Administration website, accident rates along horizontal curves — slightly tilted curving sections connecting tangent roadways — are three times as high as those for any other road design, and “More than 25 percent of fatal crashes are associated with a horizontal curve.”

Coupled with three bridges, two of which will rise nearly 100 feet over the river, these structures will pose serious risks to motorists, particularly in inclement weather, says Devane. “Who’s going to want to get on those things?” She asks.

Work in progress

City and state officials alike concede that Alternative 4B is not without its issues, stressing that the plans are still evolving.

Ricky Tipton, the DOT’s Division 13 construction engineer, says crews will work within the existing footprints of I-240 and I-26 as much as possible, minimizing the impact on adjacent neighborhoods. In areas where more space is needed to accommodate construction vehicles and materials, or to modify or add drainage structures, he continues, easements will be used to limit the amount of land that will be purchased.

As for the concerns about the bridges, Tipton acknowledges that drivers will need to exercise caution in bad weather but says the DOT will be considering safety measures such as a de-icing system as the project unfolds.

Chris Joyell, the Asheville Design Center’s executive director, says he understands the Montford coalition’s concerns. “I appreciate where they’re coming from: 4B is far from perfect; it differs from the 4B we came up with. But I think the intent to get highway traffic off the Bowen Bridge and create a real connection for the Hillcrest community to Patton Avenue is still there.”

And the fact that the DOT is listening to and tried to accommodate residents’ concerns is in itself a victory, says Julie Mayfield, the city’s liaison with the project. Besides serving on City Council, Mayfield is co-director of MountainTrue, a grassroots environmental group.

“If you ask anybody in this city over the last eight years, they would assume that I would be the person suing to stop this project,” she said during an April 18 presentation to the Montford Neighborhood Association. “If I could just begin to tell you how different that relationship is now than it was for the past 15 years, where DOT wouldn’t even talk to the city. Now, we are sitting down with them on a regular basis, working through a series of issues.”

That cooperation is having an impact, she continued. The DOT recently suggested that the eight lanes it had originally suggested through West Asheville could conceivably be reduced to six, according to Mayfield. In addition, the current design offers options for multimodal transportation along and around the project area, she said, noting that City Council reaffirmed that concern in a December 2015 resolution that also asked the state agency to take all possible measures to reduce the project’s impact and scope.

And separating Patton Avenue from interstate traffic gives the city a host of options for returning the busy thoroughfare to local use, while providing extra land along the current I-240 corridor that could hopefully be used for development, said Mayfield.

Although the city has given its blessing to the DOT’s decision to proceed with further studies to refine 4B en route to a final design, she assured the community that the discussion is far from over. “We still have a long way to go with this project,” said Mayfield. “If we don’t get there at the end, the city can always say it’s still terrible — and we don’t want it.”

No guarantees

Don’t Wreck Asheville members, however, are skeptical about the city’s ability to understand the complexities of interstate construction — or, for that matter, to get firm commitments from the DOT.

Those concerns extend to the Design Center, too. “I don’t question their sincerity in wanting to find a better solution,” says Devane. “I think they were well-intentioned and well-meaning, but the entire group had no highway engineering people involved.”

At Don’t Wreck Asheville’s suggestion, the city put out a request for qualifications back in February, seeking a consultant to bring third-party expertise to the conversation, Mayfield noted at the April meeting. Only one firm has responded so far, and Devane contends that it lacks the credentials to provide effective services.

She also questions some of Alternative 4B’s other selling points. “There’s this mythology that DOT is suddenly going to surrender all of their [obsolete] rights of way to the city to develop. If they really plan on doing it, they’ll put it in writing.”

Tipton, however, says such matters are usually considered after a project is completed, through the agency’s surplus right-of-way disposal process. As of now, he continues, “There has not been a request from the city” for any land to be transferred.

And though the idea of taking interstate traffic off the Bowen Bridge sounds nice, a closer look at traffic patterns raises questions about how much Alternative 4B will really alleviate congestion along the busy route. Much of that traffic, Devane maintains, consists of local commuters from Leicester and West Asheville who would still be using the bridge.

DOT projections, says Tipton, don’t distinguish between local and interstate traffic. Mayfield, however, says the agency’s statistics do indicate that the Bowen Bridge sees the highest traffic volume in WNC — and has the highest accident rate of any stretch of road in the state west of Charlotte.

Crash course

But while those statistics sound daunting, they may paint a distorted picture, notes transportation consultant Don Kostelec, who’s worked on several projects in Western North Carolina.

“Certainly, there are more crashes on the bridge, because congested roads tend to have more crashes,” he says, but they seldom involve fatalities. According to the DOT’s crash maps, between 2006 and 2013, only four accidents on the Bowen Bridge resulted in deaths.

“There are more fatalities on Broadway Avenue in Asheville over that same time period than there are in that section of I-26,” says Kostelec, “but nobody’s talking about needing to spend millions of dollars to fix Broadway.”

Meanwhile, the bridges proposed for I-240 and I-26 pose a much higher risk of fatal accidents, he continues — not necessarily because of of their design but because of drivers’ inclination to speed.

“The statistics are nuanced, but basically, for every 1 mile per hour of faster speed in a car, the risk of fatality in a crash increases anywhere from 4 to 6 percent, and the injury likelihood increases by 3 percent,” says Kostelec. “Regardless of what [speed limit] they post, there will be increased fatalities — that’s just the physics of it.”

And while he heartily acknowledges that Alternative 4B is the best solution on the table at the moment, Kostelec questions whether the city could recoup the tax revenue lost to right-of-way acquisition from whatever former portions of I-240 and I-26 the DOT might eventually give back to Asheville.

The regained property, he says, “ends up being so severed from the rest of the parcel and street network, I just don’t know what that ultimately entails for the economic viability of those parcels.”

Get ’er done

Although the concerns about 4B may be valid, many local stakeholders say the time for endless debate is over. “Fixing I-26 has been a top priority for the chamber for almost two decades,” says Kit Cramer, president and CEO of the Asheville Area Chamber of Commerce. While the organization has been content to sit back and let the city and the DOT haggle over the roadway’s design, Cramer says it’s high time the project moved forward.

According to a study by TRIP, a national transportation research group based in Washington, D.C., the average Asheville motorist spends 26 hours a year sitting in traffic, and collectively, local drivers waste $3.2 million worth of fuel annually, creating significant environmental impacts. With nearly 40,000 commuters pouring into the city every day and an ever-growing tourist influx, the current interchange’s deficiencies can no longer be ignored, Cramer maintains.

“I-26 coming down to a single lane in Asheville creates an unsafe, inefficient system that diminishes our economy and our quality of life,” she says. “Road construction isn’t fun or easy, but it’s necessary at times. The end result will be worth the pain of construction.”

In her remarks to the Montford community in April, Mayfield also noted that a host of regional forces are applying pressure to get the project underway. “Even if the city was to stand up and say, ‘We hate this, and we want to back up,’ nobody will stand with us to do that,” she said. “All we’ll do is take ourselves away from the table.”

That sentiment is reinforced by community representatives like Carl Mumpower, the new chair of the Buncombe County Republican Party, who says the city has dawdled long enough, catering to special interests and exacerbating a problem that only gets more complicated as time goes on.

“There’s a difference between agitating over a project and attempting to complete it, just like there’s a difference between pleasuring yourself and making love,” says Mumpower. “Asheville’s been playing with itself for decades — it’s time to embrace solutions and get this thing done. It’s a major infrastructure investment, and too much power has been given to people’s personal opinions.”

Traffic nightmare?

Don’t Wreck Asheville understands that impatience, says Gray. But with the city probably facing a decade of continuous construction, she and others question whether the long-term benefits will outweigh the headaches they say are likely to result from plowing ahead with 4B.

“It’s a long, long process to build something of this size,” notes Gray.

Devane, meanwhile, cites the current construction around Biltmore Park Town Square as an example of how these projects can drag on. “You cannot build a highway project that, during construction, is not going to slow down traffic,” she points out. “This city is going to be a traffic nightmare.”

Tipton agrees that maintaining traffic flow is a challenge, but the DOT, he explains, expects to keep “two travel lanes in each direction open during construction, and any work requiring only one travel lane to be open, or temporary complete closure, will be done at off-peak times, to minimize impacts.”

To help head off those problems, though, Don’t Wreck Asheville wants qualified experts to review the plans, looking for ways to limit the inevitable disruption.

Who pays the price?

And as the city and the DOT contend with yet another wave of dissent and debate about the connector’s impacts, they face the same central issue that has dogged the project since its inception: how to accommodate everyone’s wishes in a project where sacrifices must be made somewhere, by someone.

At the April meeting with Mayfield, for example, Montford residents bemoaned the increased noise Alternative 4B will bring to their neighborhood and called for the DOT to conduct more sound studies. Meanwhile, their Hillcrest neighbors worry that a sound wall will further isolate their community from the rest of Asheville.

“We’re already caged in — there’s only one way in and one way out,” says Opeolu “Sade” Mustakem, who’s lived in Hillcrest since 2014. “Now, you want to put this wall up to block us from the road? That’s not fair.”

For a community that’s already dealing with near constant negative stereotypes and a long history of coming out on the short end of urban renewal projects, the I-26 Connector seems to symbolize what many residents feel is an attempt to hide them from incoming tourists and the rest of the quickly gentrifying city.

“You can say that you’re trying to protect Hillcrest from the noise, but Hillcrest is nearly 60 years old — we’ve been dealing with the traffic for a long time,” says Mustakem. “I just feel like you’re putting a wall up not for our own safety but because you don’t want the outside world to know that we even exist.”

And though the DOT and city officials have held public meetings to explain the project to the community, Mustakem says many of her neighbors weren’t able to attend due to work schedules or family obligations.

In addition, she and other residents worry about the psychological effects another barrier might have on their children. “These kids have to look at this wall for the rest of their lives,” Mustakem points out. “How do you think our mental status is going to be after that? Do you even care?”

Highway projects can also have adverse physical effects, says Kostelec. “Some of the new studies are showing that kids that grow up next to major highways have asthma and lung issues at the same rate as kids living in a household filled with secondhand smoke.”

Asked about these concerns, Tipton says the project “was included in the Metropolitan Transportation Plan, which is an input to the air quality analysis used to determine that Buncombe County complies with the National Ambient Air Quality Standards and is in an air quality attainment area.”

The DOT, he notes, will continue to update its traffic noise study as the project proceeds. Neighborhoods found to benefit from a noise barrier, says Tipton, will be given a chance to vote on whether they want one.

Hillcrest resident Pat Reed understands the need for interstate upgrades but asks the city and the DOT not to tamper with the simple pleasures the community now enjoys.

“July Fourth is going to be coming up,” she points out. “I’ve never had to worry about taking [her boys] to see the fireworks, because the best view has been at the fence out here. But if they put that wall up,” notes Reed, who says she found out about the latest plans for the I-26 Connector from the evening news, “the kids won’t be able to see the fireworks, or the beautiful flowers they put out on the interstate. Why do they have to take it away from us? Let us have a home and a view.”

Making the best of it

Mayfield, meanwhile, says the city is listening and working to make the I-26 Connector “the best project it can possibly be” for Asheville.

“Everybody is concerned about this project,” she stated in April. “What I can assure you is that the city is attuned to a variety of concerns from people in Montford, West Asheville and Hillcrest, and we’re doing everything we can to address those and work through them systematically with DOT.”

The agency’s current timeline calls for drafting a new environmental impact statement by early next year. If all goes according to plan and the study is finalized and officially approved in timely fashion, the agency will begin right-of-way acquisition by 2020, with construction tentatively slated to begin soon after.

The project will be built in phases, stresses Tipton, and as design changes or other issues arise, DOT officials will continue to collect data and revise the plans to minimize the impact on the community.

For its part, however, Don’t Wreck Asheville still wants an outside consultant to evaluate the DOT’s designs and has offered to help come up with the needed funds to hire one. In the meantime, the group says it will continue to speak out until the problems it sees with 4B are addressed.

“At minimum, everybody needs to have an understanding of what the impact on our community is going to be,” Gray asserts. “If people can get a handle on how insane this is, then the conversations about how to resolve the problems can begin.”

Such debates, says Joyell, are inevitable in a small place with limited space, a range of perspectives and a penchant for community input — and the discussion isn’t likely to end anytime soon. “It’s part of city living: No one gets all of what they want. You have to give up a little. … It’s not perfect, but it represents compromise.”

For more information on upcoming community meetings, a project schedule, or other important announcements, visit the City of Asheville’s I-26 Connector project page at ashevillenc.gov, or see NCDOT’s I-26 Connector project page at ncdot.gov/projects/I26Connector. To learn more about the Don’t Wreck Asheville Coalition, visit their website at dontwreckasheville.org.

The continuing obtuseness of NCDOT is mind-blowing. I have asked at every forum I’ve attended for the past decade or more if they are looking forward instead of backward. They continue to base their traffic projections on the past and current traffic counts. Yet we are about to see a revolution in transport. Google engineers believe we have reached “peak lane” in America and that the number of cars on the road will soon plummet. Automobile analysts suggest that the number of cars may drop by 90 percent by 2030. Driverless vehicles will need a lot less road space since they all travel the same speed. In Dec. 2014 the head of the Southeast Traffic Engineers association told their annual convention it was time to stat thinking “when, not if” human drivers would be banned in cities.

Hopefully the state will continue to fail to fund this project as the driverless revolution takes hold during the next decade. Then perhaps start planning for 21st century reality instead of 20th century history.

I am not educated on this issues you’re putting forth but the timeline sounds aggressive to me.

Please realize that Google has a vested interest in tailoring projections to fit their intended investments and hoped-for revenue streams. In other words, they’re not remotely objective.

And notice, now two decades into the availability of hybrid cars and they are still priced many thousands above comparable non-hybrid cars. Not very revolutionary. It’s easy to imagine the cost of automated cars in the first decade of actual use will, similarly, be of little interest to most consumers.

So, yeah, I’m doubtful on Google’s self-serving projected timeline.

Driverless car technology is not as expensive as lithium ion batteries and production is much easier to scale. Additionally, the benefits to owners is much more obvious; a safer and more convenient car which can be insured for much lower cost. The only limitation to driverless cars is road infrastructure, something Asheville has the opportunity to preemptively address!

First child killed, driverless tech is dead. “Peak lane” is more likely to come from a TNW than from Google tech.

Second child killed, we’ll see entire companies disappear.

Excellent! Progressive. Fighting entropy one blog at a time. The model for the traffic designs in Asheville offer an opportunity to all of the creative minds in our autonomous collective. Combine travel and art. A brand new discipline. A light rail system in Asheville, like our sister city in Charlotte, would alleviate future gridlock. One priority needs to be elimination of government waste, i.e., endless studies on various forms of ‘feelings’ based concerns. Get the job done, or shut the up! Occam’s razor is the tool that or “leaders” need to refer to. Design is simple. Form follows function. After that, anything is possible. Quit wasting time and money. Do something or shut up.

Sock it to ’em, Eric. Love it …..

Your comments also remind me of the swirly-whirly, feel-warm-n-fuzzy, kumbaya city approach to that irregular piece of land across from the basilica. Gee, if we get enough citizens involved, we can surely allocate a couple inches of space to each desire voiced. Then everyone will be happy. Because they got their 2 inches, dern it! (And, we on Council, can get re-elected.)

There are times when it seems clear this city could use some therapy to adjust its’ collective, mushy, whiny karma.

Cecil — It would be helpful if you sponsored a resolution in the City Council expressing your unhappiness with this project. The City is now on record with two resolutions supporting it. This puts the City on the record of the proceedings in support of the project, meaning Julie is wrong in saying the City can easily take action against it if things aren’t sufficiently improved.

Just get the damn thing built, it’s long overdue

WTF? AVL is already WRECKED in SO many other ways…get over yourselves people.

I’m sure there are plenty of other cities that would suit you, Fisher.

I know, right…and now I have homes in other places that do allow me to flee the madness more often.

Anything that will please the military industrial complex; Ashevilles wealthy crony carpetbaggers, bad white artistes, or brand new finance money laundering businesses that ultimately prey on the Counties Real Estate Assets with the help of Mayor Esther’s Van Winkle Realty Law Firm. Just make sure to keep the true honest creative artists (visionaries) out of AVL, instead, more Pet People, and no poor people or ethnics. Just Judeo Christians Please….Keep Asheville the Whitest Art Towne in America