Robin Reeves is the sixth generation to grow up on her family’s Madison County farm — a lineage that dates back to before the Civil War. Reeves spent much of her youth helping her parents raise cattle, burley tobacco and tomatoes as well as her extended family in Sandy Mush. As an adolescent, she sold produce to Ingles to earn spending money.

“We worked together, we played together. You can’t trade those memories for anything,” remembers Reeves. And after her father, Burder Reeves, passed away in 2009, Robin and her son moved back to the farm from Swannanoa to help her mother keep the family homestead going.

But times were tough, and the farm suffered for it. “Financially it was hard, because the tobacco buyout happened, and we weren’t getting that income anymore,” she explains. “It was basically me trying to run the farm alone.”

Reeves’ story is a familiar one in North Carolina, a state long defined by its robust agricultural output. According to the Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, the state’s $78 billion agricultural industry employs 16 percent of the workforce. North Carolina leads the nation in tobacco and sweet potato production and ranks second in poultry, Christmas trees, hogs and trout.

But encroaching development, the rising cost of land and an aging farming population have put a strain on agricultural pursuits across N.C. And in the mountains, where topography and poor soil conditions already limit the amount of arable land, the loss of farmland is felt even more acutely, says William Hamilton, farmland program director for the Southern Appalachian Highlands Conservancy.

“Only 2 percent of the region’s land mass consists of these prime soils, and part of that has already been converted to a developed land use,” he explains. Much of WNC’s prime agricultural land lies near rivers and creeks where, Hamilton says, it’s “highly threatened, because those areas are typically easy to develop.”

Government agencies and private land trusts are fighting back, however, working hand in hand with farmers to preserve rural communities through conservation easements and other agreements. And there’s far more than just heritage and money at stake. Preserving farmland, notes Hamilton, is important for a whole host of reasons, including “food security, soil preservation, open space for wildlife and scenic beauty, groundwater recharge, the preservation of our cultural heritage, and the long-term security of a unique economic resource.”

A long slog

Working to preserve the state’s agricultural land “has been a long slog,” says Edgar Miller, director of government relations at the Conservation Trust for North Carolina. The nonprofit partners with local land trusts across the state and lobbies the Legislature on their behalf.

Under a conservation easement, the property owner retains possession of the land but either donates or sells the right to develop it, typically for significantly less than the market value. The money comes from grants, government programs and/or land trusts, which also coordinate the process and hold the easement once the transfer has been made.

Finding the money, however, isn’t easy. Although The Farmland Preservation Enabling Act was passed in 1986, no money was allocated for the trust fund established by the state law until 1996, notes Miller. And even then, funding remained negligible until 2005, when the law was amended to broaden the scope of projects that could be supported by the renamed Agricultural Development and Farmland Preservation Trust Fund.

Each year, the trust fund awards a limited number of grants to land trusts and other conservation programs. Together with federal money, those grants provide most of the funding for the approved projects and easements. The 2005 amendment also established voluntary agricultural districts. These 10-year provisional agreements are a way to “get the farmer in the door and get him used to operating under an easement,” says Miller. “The theory is that they will ultimately put it under an easement in perpetuity.”

The Southern Appalachian Highlands Conservancy has protected over 6,000 acres of farm properties in WNC, focusing on “intact agricultural communities where the primary land use is agriculture” in Buncombe, Haywood, Jackson, Madison, Yancey, Avery and Mitchell counties, Hamilton explains.

Changing the mindset

Facing an uphill battle, Reeves and her family reached out to a longtime friend about securing an easement to protect their property from future development. Eventually, Reeves was put in contact with the Southern Appalachian Highlands Conservancy, which she says helped her overcome her reservations about transferring the development rights.

“I always had this thing about not liking people telling me what to do with my property,” she reveals. “There’s a lot of farmers with the same stubborn mindset that I have, but William and the Southern Appalachian crew are great to work with.”

Preserving the Reeves farm was an important symbolic objective for the nonprofit, says Hamilton; the SAHC recently helped preserve three separate parcels totaling 318 acres. “This farm is representative of agriculture in Western North Carolina, and the Reeves family made a gift to this region in permanently protecting this farm. This project represents five years of hard work on the part of the land trust, the landowners and the agencies involved.”

Securing an easement is a complicated process that often spans several years, notes Ariel Dixon, farmland preservation coordinator for Buncombe County’s program, a division of the Soil and Water Conservation District. She typically works on two to three such projects at a time, meeting with the property owner, getting the land surveyed and applying for state and federal grants.

“In general, we have just a handful of different grant programs that the county can apply for,” she explains. “Occasionally we’ll get other small grants; we’re lucky to get some of the closing costs for our easements from Buncombe County, but that’s not always the case.”

Land trusts like the SAHC, however, have more wiggle room when it comes to securing private donations to supplement government funding. “Supporting SAHC as a member or philanthropic leader is a great way to provide direct, needed support for our farmland conservation efforts,” notes Hamilton.

Hammering out the details can also require a fair amount of compromise on both sides. Open communication and establishing a positive working relationship with property owners during the application process is key, says Dixon. “A lot of the landowners we work with are amazing farmers who oftentimes were born on the property and grew up there. We want to make them understand that even though they’re working with a government agency, the county is not going to take their land.”

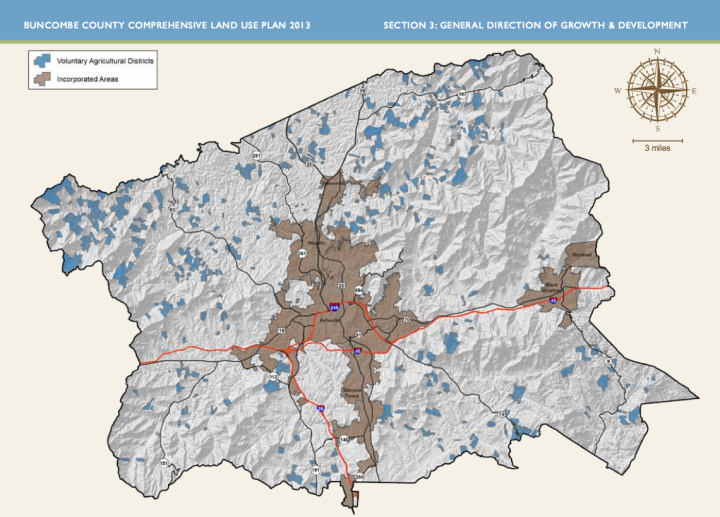

And for those who aren’t ready to commit to a permanent easement, notes Dixon, there are other options. Voluntary agricultural districts, which consist of 50 or more acres of farmland within a 1-mile radius, exempt farmers from nuisance ordinances, sewer and water assessments, and other restrictions. Enhanced VAD status also allows farmers to generate up to 25 percent of their sales from nonfarm products. Landowners can withdraw after 10 years and are free to apply for a permanent easement at any time.

“Even if it’s just that small extra protection for the farmers, it’s crucial that they understand that it’s out there,” says Dixon.

Toward greener pastures

Despite these local entities’ success in preserving agricultural land, there are a number of obstacles to accomplishing grander goals.

“State funding has been sporadic and certainly significantly below the demand,” says Miller, who estimates that less than a third of such grant applications get funded. Budgetary limits also make it hard to pull together larger-scale, community-based easement projects.

“Funding is definitely difficult,” agrees Dixon. “Every year it gets cut again and again.” As a result, her department is getting creative in how it markets the program. “We have such a huge tourism industry, and I think a lot of people come here because of the picturesque, rolling hills and farms framed by the Blue Ridge Mountains,” she notes.

Recently, for example, Buncombe’s farmland preservation program received a grant from the county’s Parks and Recreation Department to establish a pilot “farm heritage trail” in northwest Buncombe. “It’s a driving route with various stops and activities that takes you through some of the most beautiful farm areas and countryside of that part of the county,” Dixon explains. Designed to bring potential paying customers to the farms while building public support for preservation, the trail is expected to be completed by next April.

Ironically, however, even land that’s already been preserved can pose an equal challenge: how to put it back into active use. “We’re really trying to get land trusts to get that land in agricultural production, and particularly to provide creative ways to get that land into the hands of new farmers,” notes Miller.

Farming schools and educational programs like the Organic Growers School in Candler have gone a long way toward rekindling young adults’ interest in farming, he says, but in many cases, “Young farmers can’t afford the land” they need to make a go of it.

To help address this, the Southern Appalachian Highlands Conservancy has established a 103-acre community farm in Alexander. “The farm was donated to SAHC because the landowners wanted to see it continue in agricultural use,” Communications Director Angela Shepherd explains. The nonprofit recently launched an incubator program there, giving beginning farmers low-cost access to both land and hands-on learning opportunities.

Planting the seeds

For Reeves, the conservation easement has had both immediate and long-term benefits. the money she received enabled her to buy a new tractor and hay equipment, and she’s working on building a facility for on-site retail sales. “The tractor has a closed cab with an air conditioner and heat,” she notes enthusiastically. “We’d never had a cab tractor before, so I feel very, very blessed that we were able to get one.”

In addition, says Reeves, placing the land under an easement has alleviated the stress of an uncertain future. “My mom is 75. She had a heart bypass in January; I’ve already had two heart attacks. It’s one of those things where we want to make sure it’s all planned out and taken care of, that the legacy plan is there, so that if something does happen to us, things will be taken care of for the grandkids.”

And with new developments seeming to spring up in the mountains “almost every day,” she continues, keeping prime farmland available is really a matter of the entire region’s survival. “We want to support local food — Asheville’s great about that. But if we lose all the farmland to development, we won’t have that local food here.”

Preserving agricultural land for future generations “is a long process, but it’s worth it,” asserts Reeves. “That way you know there won’t be a bunch of houses looking at each other on prime farmland that’s fed your family for many years.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.