On Feb. 1, 1889, an elated crowd of Asheville locals braved frigid temperatures to watch history in the making in Pack Square. That day, the city’s newest innovation — the electric streetcar — departed on its maiden voyage through the city. From that single car, Asheville’s first mass transit system would evolve into the second-largest trolley service in the entire country for its time.

Until its demise in 1934, the trolley would play a central role in transforming Asheville from an isolated village into a modern city, bringing the possibilities and pitfalls of modernity with it.

Over a century later, Asheville once again struggles to accommodate increasing numbers of tourists, transplants and natives attempting to navigate the city. As city planners and residents wrestle with the latest growing pains, increasing numbers of citizens are calling for the city and state to invest in a future beyond the car.

A streetcar named development

At the turn of the 20th century, Asheville boomed with exuberant growth and expansion. The coming of the railroad in 1880 had opened the region to tourists and developers eager to capitalize on the area’s natural resources and scenic beauty. But getting visitors from place to place around the city was an arduous task for mule and man alike.

That all changed with the trolley’s introduction. “A new era was begun,” wrote authors David C. Bailey, Joseph M. Canfield and Harold E. Cox in their history of the Asheville streetcar system, Trolleys in the Land of the Sky. “No longer would Asheville be a simple mountain town, sparked only by visits of health-seekers and the wealthy fashionable from the east.”

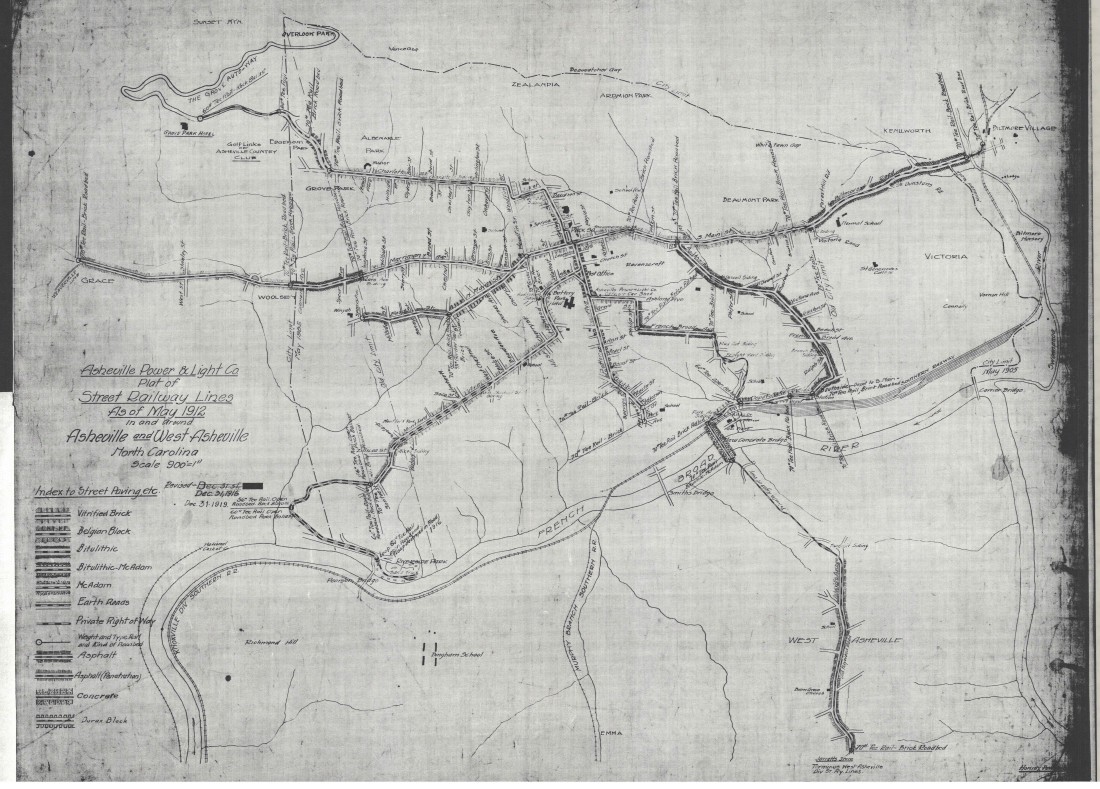

By 1907, the streetcar system was carrying over 3 million passengers a year, the most of any in the state, according to the N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. At its peak in 1915, Asheville’s system was running 43 individual cars on approximately 18 miles of track.

The trolleys not only ferried people around the city but also helped shape it. Bankrolled by private investors, trolley lines spurred development in nearby villages like Montford and Ramoth (which encompassed the neighborhoods between Weaver Park and the Grove Park Country Club). West of the city, the sparsely populated area around the Sulphur Springs Resort grew into what is now West Asheville via the trolley line established by Pennsylvania investor William Carrier. Farther north, Weaverville and Woodfin were brought closer than ever through R.S. Howland’s efforts to establish trolley connections to Asheville, including the Craggy Mountain Line.

Many of the early companies operating the lines struggled to stay solvent, however, and several were sold or put into receivership throughout the late 1800s, according to Bailey, Canfield and Cox. In the early 1900s, the system was consolidated under the Asheville Power & Light Co., which became Carolina Power & Light in 1926.

CP&L ran the trolleys, paying usage fees to the city to operate on public streets, until the demise of the trolley system in 1934.

Something old, something new

Today, after decades of financial struggles following the stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression, Asheville again finds itself in the midst of a renaissance. According to U.S. census data, the city’s population grew from 74,000 in 2000 to nearly 90,000 residents currently. This doesn’t include the estimated 40,000 commuters who drive into the city for work each day, according to a 2017 study by national transportation research group TRIP.

In addition, the Buncombe County Tourism Development Authority estimates that an average of nearly 30,000 people visit Buncombe each day, while the Asheville Regional Airport reported record numbers of travelers for the fourth straight year in 2017.

Unlike the early 1900s, however, getting around today’s Asheville is predicated on motor vehicles. TRIP’s study noted that the average Asheville motorist spends 26 hours a year waiting in traffic; collectively, Asheville commuters use roughly $3.2 million worth of fuel annually.

While some commuters must drive out of necessity, there are many who could eschew cars if a viable alternative were offered, says Mike Sule, executive director of Asheville on Bikes. “The only way to reduce congestion is to diversify the mode share,” he says. “If we want a city that people can flow and move through, then we need to provide transportation options for a variety of people.”

Within the city itself, few options exist for those without a car beyond the Asheville Redefines Transit bus system. Since 2010, the city has worked with community stakeholders to redevelop ART into a modern transit system, expanding service hours and routes, hiring a new management company to oversee the system, and modernizing its bus fleet to include hybrid, biodiesel and, in the next few years, electric buses. Currently, ART operates 17 individual routes, serving 2.1 million passengers last year.

The recent hiring of a new management company, RATP Dev, in October to oversee the ART system has also paid dividends, according to the city, which recently reported that on-time performance had improved from around 50-60 percent historically to 67 percent as of January.

Solidarity, segregation and streetcars

Many of the streets and neighborhoods where ART buses now run developed around the streetcar system. But the trolley’s impact on Asheville went beyond its influence on the city’s physical layout. The streetcar system soon highlighted issues of workers’ rights and racial segregation.

Asheville streetcar employees were paid a spartan 12 cents an hour as late as 1913, when the Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employees of America, Division 128, staged a strike that crippled Asheville’s trolley service for three days, forcing ownership to increase wages over the next several years. The streetcar workers’ union would eventually evolve into the Amalgamated Transit Union Local 128, which continues to represent the city’s transit employees today.

While the trolleys may have enabled the growth of suburban communities outside Asheville, that growth reflected white residents’ desire to maintain racial segregation between neighborhoods.

Nor was the trolley system itself immune from such bigotry, as Bailey, Canfield and Cox illustrate. When an African-American park was established in Ramoth in 1902, black residents began to use the East Street Line in significant numbers, causing white patrons to complain.

Citing “a lack of business” and an “unsafe” trestle crossing at Reed Creek, the line’s owners abruptly discontinued service to the area on July 6, 1902, according to the authors. When the Ramoth aldermen approved a new line to the community several days later, it was with the added stipulation that “prohibited the street railway from operating a ‘Negro park’ on or near the new line.”

Transit for the rest of us

Economic disparities are apparent today in the makeup and concerns of the ART system’s ridership. According to a 2013 ART rider survey, 63 percent of respondents had no other transportation option, while 78 percent of riders earned under $25,000 a year.

Addressing the needs of necessity riders was the catalyst for the formation of Just Economics’ People Transportation Campaign in 2012, says Amy Cantrell, one of the initiative’s organizers. “When we went through the ART makeover, necessity riders actually lost service in a lot of ways,” she notes, including a reduction of stops to improve on-time performance and a tightening of service hours. “We were sort of ballasting on-time performance on the backs of the most vulnerable [residents].”

In response, the People’s Transportation Campaign developed a 19-point transit agenda that called for more service to neighborhoods that rely heavily on ART for transportation, an increase in evening and weekend service hours, improved bus stop infrastructure and better rider representation on the city’s Transit Committee.

While the group celebrated the successful implementation of its agenda last December, says Cantrell, campaign members aren’t resting on their laurels. “We’re not anywhere near the kind of robust transit system that we know we need as a necessity rider.”

With the city engaged in its next Comprehensive Plan process, as well as a major update to its Transit Master Plan in the coming year, transit advocates are devising a new set of goals on behalf of riders.

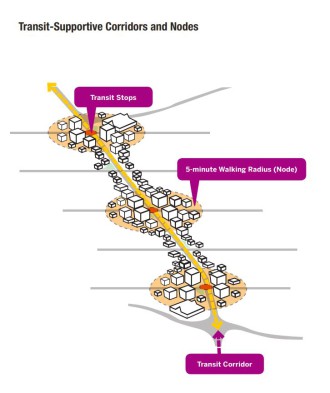

For its part, the city is encouraging mixed-use development around centralized “nodes” along the transit system in the new plans, which they hope will make accessing and connecting to the ART system easier for residents, while providing a viable alternative to car-based commuting, city transportation staff stated in an email to Xpress.

End of an era

The automobile’s rise spelled doom for Asheville’s trolleys. By the 1920s, improved road conditions and wider ownership of motor vehicles had begun to subvert the electric streetcars’ hold on the city.

The final death-blow came with the 1929 stock market crash, which plunged Asheville and the rest of the country into the Great Depression. By 1934, the city decided to phase out the trolleys in favor of a modern bus system. Just as they had gathered back in February 1889, citizens came to Pritchard Park on Sept. 7, 1934, to see the trolleys off one last time.

A recap of the send-off in the Asheville Citizen noted that, “Although the general motif was gay, there was an undercurrent of sadness among many of the passengers at the passing of the familiar streetcars which had served the city so long.”

Many of the trolleys wound up at Fortune’s Street Car Tourist Camp on Hendersonville Road as reconfigured campers; at least one served as a dwelling in Biltmore Forest into the 1950s.

In 2001, vintage railroad buff Rocky Hollifield founded the Craggy Mountain Line to preserve a 3-mile section of track in Woodfin, the last surviving stretch of Asheville’s trolley system. Today, the volunteer-run nonprofit operates short excursion trips on Saturdays from April through October, as well as special holiday events.

Only two original Asheville streetcars are known to remain in existence. Craggy Mountain Line owns both, and Hollifield intends to restore them and put them back in service.

“Our desire is to bring the two Asheville cars back to life, so people can come here and step up into a piece of our local history,” Hollifield says. But restoring those cars — both of which are in a state of disrepair — requires time and money, for which Hollifield hopes to find a grant or funding source in the near future.

Beyond the bus

More than eight decades after the trolley’s final run, public interest in multimodal transit is experiencing a resurgence. The 2013 Millennials & Mobility study by the American Public Transit Association noted that young commuters increasingly want to live in cities that offer a variety of transit options and prefer modes of transportation that allow them to work while traveling.

Locally, Sule says, “There’s every indicator that our community wants active transportation: There are ‘Slow Down’ signs everywhere. If you look at the South Slope survey on the city’s website, bicycle parking is a higher priority than vehicle parking.”

In August 2016, the city hosted a preliminary community meeting to discuss possibilities for a shuttle program to ferry people among West Asheville, the River Arts District and downtown. According to the city’s Transportation Department, an analysis of the shuttle proposal will be included in the city’s updated Transit Master Plan, which is expected to be released in draft form by April.

Asheville has also invested in developing its greenway system, which will eventually link downtown with points east, west and north (See “Road to redevelopment,” Sept. 16, 2016, Xpress). To gauge interest in a possible bike-share program, city staff plans to launch a feasibility study this year. Such a program would allow residents and visitors to pick up a bike from a station in one part of the city and return it to another station when finished.

Diversifying transit throughout the city offers a multitude of benefits for the entire community, says Sule. In addition to improved safety for pedestrians, cyclists and motorists, a diverse transit system encourages economic growth, “primarily because people are moving slower through those corridors, and they’re able to notice more of what a particular corridor has to offer,” Sule contends.

With Asheville’s population steadily growing, Cantrell says that it’s time for the city to develop a transportation network that mirrors larger cities in the country, where public transit is easily accessible and reliable. “It’s more sustainable, better for the environment and much better on traffic congestion,” she notes.

A robust transit system also facilitates community engagement and helps bridge equity gaps, Cantrell adds. “Lack of access really hampers the life of our overall community and participation in the community as a whole. Transit’s a real intersectional issue, in terms of food and security, the struggle for affordable housing and for economic opportunity for better jobs.”

The trouble with transit

But if city officials are open to the idea of a diversified transportation landscape, implementing those ideas is a more complex puzzle. “Challenges can be financial, physical or social,” says the city’s transportation staff, especially in a region with limited available land for right of way expansion.

Last year, for example, Asheville’s ambitious greenway plans ran into a snag due to ballooning construction costs, causing city planners to put some projects on hold until additional funding sources could be identified. And plans to incorporate multimodal elements into the Interstate 26 Connector project remain up in the air, as the city and the N.C. Department of Transportation haggle over who pays for those aspects of the design.

While Sule acknowledges that funding is always a challenge to any transportation project, he contends that the public supports increased investment in alternative modes of transport. “We just passed a $30 million bond referendum for transportation, which speaks to how much our citizens desire active transportation options,” he says.

Initiating such projects also requires regional cooperation, notes Lyuba Zuyeva, director of the French Broad River Metropolitan Planning Organization, a conglomerate of municipal and county representatives that works with state agencies to set transportation priorities in WNC. “There has been an increase in cross-county commuting patterns in our region over the last 15 years and there is not currently a regional transit authority in place to help connect residents from one part of our region to another,” says Zuyeva, unlike other areas of the state like the Triangle, where a regional transit authority supports local transit services to facilitate intercounty transportation.

For Cantrell, the issue of funding presents a values question for the city. “Budgets are moral documents,” she says. “Investing in transit might seem like a lot, but there are social costs that we don’t compute in sometimes, whether that’s health care, social services because people can’t get to work, the environment. Investing in transit is actually much cheaper than reaping those costs later on.”

DOT or DOn’T

Outside agencies, like NCDOT, which controls the many of Asheville’s roadways, must also be on board with the city’s transportation goals. Points of disagreement recently emerged over NCDOT’s proposed widening of Merrimon Avenue, which some residents, advocacy groups like Asheville on Bikes and the members of City Council have opposed (See “Residents to DOT: Let us participate in Merrimon planning,” Jan. 24, Xpress).

While NCDOT has endorsed a “complete streets” approach — which calls for accommodating all street users, including pedestrians, cyclists and transit users as well as motorists — since 2009 and recently adopted a Vision Zero plan that emphasizes multimodal transportation, Sule alleges that Division 13, which oversees DOT operations in Western North Carolina, has not prioritized such initiatives in its projects locally. “The agency that is tasked with providing transportation to our citizens is ironically the No. 1 obstacle to safe, accessible transportation options,” he says.

In response, Division 13 spokesperson David Uchiyama points to NCDOT’s 2018-27 State Transportation Improvement Program, where a host of pedestrian, sidewalk and multimodal priorities are listed for the Asheville area, based on the state’s Strategic Mobility Formula, which allocates revenue based on data-driven scoring and local input. Uchiyama adds that residents’ ire is often mistakenly pointed at DOT, when transportation initiatives are generated by regional groups like the French Broad River MPO, which DOT works in partnership with.

According to Zuyeva, DOT sets aside anywhere from 4 to 10 percent of available Regional Impact and Division Needs funding for nonhighway modes of transportation. But under state law, municipalities and local agencies must match state funding for any pedestrian or bicycle improvement project, while federal and state statutes limit how much highway transportation funding can be used for multimodal projects.

The French Broad River MPO met with local stakeholders and NCDOT officials on Feb. 13 to discuss goals aimed at increasing mobility for low-income residents, seniors and those with disabilities in WNC through Federal Transit Administration grants and partnerships with nonprofits and the private sector.

On March 21, NCDOT will host a Summit for the Statewide Strategic Transportation Plan in Raleigh to review and discuss statewide initiatives. In addition, the N.C. Public Transportation Program will host a five-day conference beginning April 20, and the N.C. Association of Metropolitan Planning Organizations will host its annual conference on April 24, during which transportation issues will be discussed.

Back on track

And what of the trolley system? Could Asheville’s transportation future feature a return of the streetcars, as cities like Charlotte and San Francisco have done?

Not anytime soon, according to Asheville’s Transportation Department, citing upfront costs, logistical challenges and questionable returns as prohibitive factors to any such project.

City transportation staffers say they are looking at the possibility of eventually transitioning frequently used ART routes into rapid transit lines, which “function more like conventional rail systems.” However, they add, “It’s too early to discuss whether ridership and other conditions could meet the requirements that would be necessary to justify a BRT [bus rapid transit] system.”

While a return of a streetcar system in Asheville might not be on the horizon, the vestiges of the original trolley lines could play an important role in revitalizing nearby Woodfin’s waterfront, where town and county officials announced plans last year for a $13.9 million project that would include a 5-mile stretch of greenway, a new park and the region’s first constructed whitewater wave.

The location of this new project happens to be located along the Craggy Mountain Line’s right of way, says Hollifield. “The fact that we’re going to have a park at the end of our line is very exciting,” he notes. “It’ll give people a chance to ride a trolley, maybe walk the greenway, do some river riding and just see a lot of the area.”

In addition, Hollifield has grand plans for a depot location at the other end of the line in the center of Woodfin, which could include a small museum, food vending area and other amenities.

While his organization is still seeking funding assistance for the depot project, Hollifield says the goal in the next couple of years is “to have it where people can come and have a place to feel, see, hear and smell the experiences they would have been able to have almost 100 years ago.”

Lessons from the rail line

As the city continues to plan for its transportation future, residents can keep up with current initiatives and provide feedback on projects by visiting Open City Hall, attending upcoming workshops, or applying to serve on one of the city’s transportation-related boards and committees.

Meanwhile, Cantrell says the People’s Transportation Campaign will continue to focus on improving the ART system, with hopes to expand its efforts into Buncombe County. “That’s on the horizon,” she says. “There are so many opportunities where it would make sense to advocate around county transit — it’s a huge need.”

She encourages interested residents to get involved with the campaign by visiting justeconomicswnc.org or becoming a member of the Better Buses Together Facebook group.

Sule, meanwhile, encourages residents to sign up for his organization’s newsletter. “If you want to find out the events and the opportunities to volunteer, ashevilleonbikes.com is the place to go,” he notes. “You’ll get to know of all the major cycling events, our advocacy campaigns and the call to actions.”

Perhaps the easiest thing people can do is learn from the city’s past efforts and mistakes in maintaining multimodal options like the once-famed trolley system, says Hollifield. “You had a system that was so efficient,” he says of the trolleys. “They were quiet; they used no gas or oil, no tires or batteries. You didn’t have to pave a road every few years. I don’t think the buses are going anywhere anytime soon, but I do think we’re learning that we should have held on to this railroad history and kept it.”

Before you comment

The comments section is here to provide a platform for civil dialogue on the issues we face together as a local community. Xpress is committed to offering this platform for all voices, but when the tone of the discussion gets nasty or strays off topic, we believe many people choose not to participate. Xpress editors are determined to moderate comments to ensure a constructive interchange is maintained. All comments judged not to be in keeping with the spirit of civil discourse will be removed and repeat violators will be banned. See here for our terms of service. Thank you for being part of this effort to promote respectful discussion.