Few crops have been as central to North Carolina’s economy and culture — or as controversial — as tobacco. Historically, its high market value and the relative ease of growing it made tobacco a staple for many Western North Carolina farmers. As late as 2002, 1,995 mountain farms grew tobacco.

The crop’s prevalence, however, was closely tied to the long-standing quota system, which regulated where it could be grown and set a guaranteed price range each year.

Significant government involvement with the industry began during the Great Depression, but changing times and social attitudes eventually caught up with the program. Increasing health concerns and lawsuits ultimately led to the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement, which restricted tobacco advertising and gave states substantial payments to offset Medicare expenses and fund anti-smoking programs. In conjunction with other changes, this accelerated a continuing decline in sales of American-grown tobacco.

Of more immediate significance for local farmers, however, was the 2004 Fair And Equitable Tobacco Reform Act, which put an end to the quota system.

Commonly known as the “tobacco buyout,” the federal law gave both quota holders and actual growers annual payments for 10 years to help them transition to new enterprises or find other income streams. But there was no obvious substitute crop, and since the end of the payment program in 2014, many farmers across the Southern Appalachians have faced both the challenge of replacing lost revenue and, at a deeper level, a kind of identity crisis.

Although assorted state agencies and nonprofits have tried various approaches, the lingering effects of the buyout continue to confront rural mountain communities.

Rise of the golden leaf

Commercial tobacco production in North Carolina stretches back centuries. In the 1600s, European settlers found that it was one of the few crops that would consistently grow in all of the young colony’s varied climates and soil conditions.

By the 1920s, burley tobacco had become the dominant strain in WNC. Its adaptability, coupled with increased demand in the early 20th century, made tobacco cultivation a cost-effective way for mountain farmers to supplement their income, says Charlie Zink, a former grower who’s now executive director of the Madison/Buncombe County Farm Service Agency office. “Burley is what gives a tobacco product its flavor,” he explains. “It’s considered the ‘salt’ of tobacco products.”

But when the Great Depression hit in 1929, an already unstable tobacco market was exacerbated by a glut, as desperate farmers tried to compensate for falling prices by producing more. In response to the crisis, the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 instituted a quota system, limiting tobacco production primarily to the Southeast and establishing strict controls on the number of tobacco-producing farms, the poundage each could grow and the prices companies would pay for it.

“Tobacco quotas were a fixed asset; the person who owned the land owned the quota,” notes Zink. “The owner could grow tobacco if he wanted to, or could lease it out through cash or sharecropping to growers.”

North Carolina led the U.S. in tobacco production through most of the 20th century, and it still does today. In 2012, the state produced 381 million pounds — about half of all the tobacco grown nationwide — and generated over $700 million in sales, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture figures.

In WNC, Buncombe, Madison and Yancey counties produced the most tobacco. “For many of our mountain farmers, the burley tobacco check was a staple that paid for Christmas and property taxes at the end of the year,” says state Rep. John Ager, whose family owned a quota. “My grandfather-in-law, James McClure, was very involved with promoting the Asheville burley tobacco market in the ’20s and ’30s.”

Zink tells a similar story. “You could always tell when the economy was bad, because more tobacco was grown to balance income. It paid for my college; it paid for my first car. After I got married, it paid our taxes on our house.”

Changing attitudes

By the 1970s, however, the federal government was facing increasing pressure to end the price supports and convert to a free market system. And in 1981, the feds did stop funding the tobacco program, instead requiring companies and growers to pay for it via assessment fees.

Ironically, health proponents and Big Tobacco found themselves on the same side of the argument for once. The tobacco companies, says Zink, “had been in favor of getting rid of the quotas for years prior to the buyout: It lowers their costs.”

Tobacco sales declined nationwide through the 1980s and ’90s, due to fewer people smoking and increased competition from cheaper foreign tobacco. And some farmers, perhaps seeing the writing on the wall, stopped growing the crop.

Ager says his family leased its quota “to a neighbor for a year or two, and then to whoever gave us the best price. We were running a dairy farm in those days, and I think there was some family ambivalence about tobacco as an unhealthy product.”

Finally, in 2004, President George W. Bush signed the Fair and Equitable Tobacco Reform Act, which ended both the price supports and quotas. The Tobacco Transition Payment Program, administered through the USDA, began the following year.

“Quota owners received $7 a pound, based on what their quota from 2002 was,” says Zink. “Your tobacco producers — the people who actually grew it — got $3 a pound, based on price averages from 2002 to 2004.” But even though that time period had seen the highest prices, farmers still collected less than they traditionally had, because total poundage was down — and meanwhile, the clock was ticking.

Funding for the roughly $10 billion buyout came from the tobacco companies. “Taxpayers didn’t pay one dime — not even my salary,” stresses Zink. And each year, farmers could choose to take their money in a lump sum or continue getting annual payments.

Untrodden ground

In Western North Carolina, the tobacco buyout’s impact was felt almost immediately. In Madison County, for example, the total acreage devoted to tobacco cultivation dropped from 1,400 in 2004 to roughly 100 today. And during the same period, the number of tobacco farmers in neighboring Buncombe plummeted from about 800 in 2004 to just 20.

Many older farmers used the payments to fund their retirement, says Steve Duckett, director of the N.C. Cooperative Extension’s Buncombe County Center. Others invested in new equipment, education or infrastructure.

But for those who chose to remain in the game, the deregulation made it hard to turn a profit. Within a year, the price of tobacco had dropped from $1.98 a pound to $1.50. And with no price guarantees and substantial shipping costs to get their product to the nearest market, farmers risked incurring significant losses.

For many growers, the prospect of starting over with a different crop or even a whole new business proved less appealing than simply cashing out. “There’s some truth to the saying ‘You can’t teach an old dog new tricks,’” notes Duckett. “Unfortunately, a lot of that land [in Buncombe County] is growing septic tanks right now.”

Meanwhile, those who did press on found themselves in unfamiliar territory.

The buyout, says Duckett, “introduced a lot of uncertainty into the equation. We were in a whole new world here in the Southeast, so we had to look at the farm’s resources: What could they grow? And whether it’s vegetables, nurseries, greenhouses, agro-tourism or the local food market, there really wasn’t an easy solution.”

A lot of Madison County farmers expanded their livestock production. But when drought hit the mountains in 2008, “The market went down, and many had to sell their livestock off at a loss,” says Zink. Some leased their land or took jobs in Asheville and other urban centers.

Meanwhile, the lost tobacco revenue was rippling through whole farming communities, he continues. “You have to look at the effects it had on other businesses: ag stores, the fertilizers and chemicals bought to grow the tobacco.”

Governments were also affected. “Growers,” notes Zink, “used a lot of their tobacco money to pay taxes. Since the buyout, local government has had to take up that slack.”

All in the family

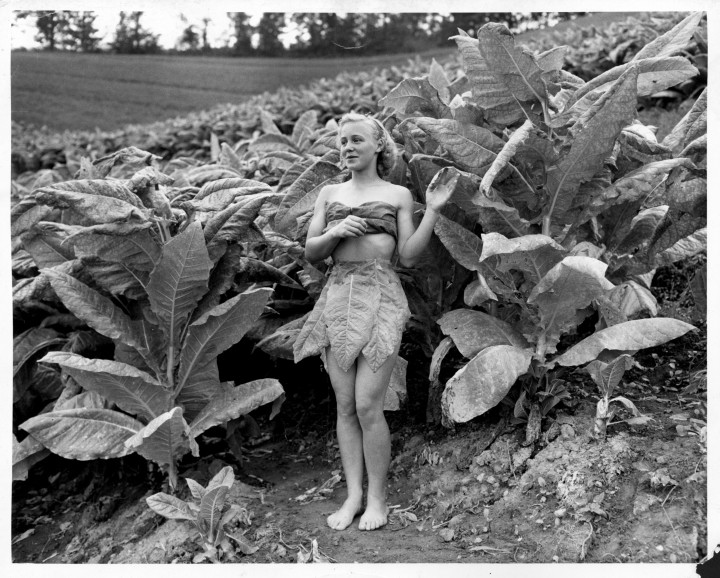

For the most part, though, the national debate about tobacco —which helped drive the paradigm shift that eventually led to both the Master Settlement Agreement and the tobacco buyout — focused more on health risks and Big Tobacco’s efforts to manipulate the system. What got far less attention was the farmers themselves and how much the crop meant culturally to many rural communities. Robin Reeves, whose family has farmed in Madison County since 1840, fondly recalls the way they grew tobacco when she was a child.

“Tobacco meant mothers could stay home with the kids,” she points out. “Not to say the mothers weren’t working — they were helping in the fields. But it was a cool crop, and parents could actually be there.”

The quota system, notes Reeves, gave her family some financial security, meaning they could devote more resources to other farm needs. “We kind of knew what we were getting into, what the prices would be. We could always tell when we got our tobacco to market before Christmas or after: It was a much leaner Christmas if it was after.”

Tobacco also fostered a sense of community. “Local boys would come and help us during the season,” she remembers. “It helped them make money and gain experience. We all worked together, which we’ve lost to some degree.”

Reeves’ family invested most of their buyout money in both livestock and retail tobacco sales. “We were lucky: We had rental properties in Swannanoa and built a convenience store, 6 Pac Smokestack,” she explains. “Daddy bought a new Chevy truck and that was that.”

But while Reeves, who also serves on the board of the Buncombe County Farm Bureau, says “The checks were nice,” she’s less sanguine about the buyout’s overall impact on her community. “It changed the whole dynamic: We used to silo together; we’d cut tobacco together. All that’s gone away. After the program ended, it was kind of like, what do we do now?”

Building blocks

Since 2000, several entities have been working to help rural communities make the big transition. In North Carolina, both the Golden LEAF Foundation and the Tobacco Trust Fund Commission, have tried to foster new economic opportunities in the affected areas.

“There was a real focus on economic development — the idea and hope that we could help develop another crop as lucrative and productive as tobacco was,” says Billy Clarke, who’s served on several Golden LEAF committees over the years. The nonprofit foundation, he notes, has invested in everything from community college job programs to business development in economically depressed counties across the state.

Locally, Golden LEAF funding helped bring two major breweries, Sierra Nevada and New Belgium, to the region and also played a part in developing the WNC Regional Livestock Center in Canton in 2010. “I think it had a positive impact, with lots of jobs created,” Clarke reflects. “We made grants to Henderson, Madison, Yancey and Haywood counties, among others, through our Community Assistance Initiative.”

The Tobacco Trust Fund Commission has also seen many projects blossom in the region, says Executive Director William Upchurch. “One of our most successful programs is WNC AgOptions, which provides financial opportunities to farmers looking to try a new crop or agricultural business, or just doing something value-added to their operation.”

The trust fund was also instrumental in developing the livestock center, working with local nonprofits such as WNC Communities. “It had gotten to the point in the west where there wasn’t a viable auction opportunity for farmers to carry livestock to,” he explains.

In addition, the trust fund has invested in various community college programs. Project Skill-Up, says Upchurch, “helps provide training for those looking to try something new on their farm, or those who’ve decided on a different career path.”

Private nonprofits such as the Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture Project have lent a hand as well. “We started in anticipation of the end of tobacco: Our entire local food campaign was a strategy for making the transition,” notes Charlie Jackson, ASAP’s executive director.

And as tobacco production has diminished, says Jackson, he’s seen an uptick in the amount of fruit and vegetables grown in the counties around Asheville. “In the early years we worked with farmers on new crops, but we soon realized that what we needed were better markets,” he recalls. “All of our efforts are geared to building demand and then helping farmers meet that demand with successful businesses.”

Through certification programs like Appalachian Grown, marketing projects like the Local Food Guide and the annual Business of Farming Conference (this year’s edition was held Feb. 20), ASAP has helped local farmers fill the tobacco void and reinvigorate mountain farming culture.

“Tobacco is so connected to the history, economy and culture of our region,” notes Jackson. “It kept our farmers — and, therefore, our beautiful landscape of small farms.” And now, he continues, “We’re emerging from tobacco as a world-class destination for local food and farms — one in which the community is engaged.”

Show me the money

Despite these organizations’ impressive work, however, state allocations for both Golden LEAF and the Tobacco Trust Fund Commission have been slashed. Initially, says Upchurch, the fund was getting $35 million to $40 million annually in settlement agreement money, but within a few years, the commission began seeing cuts. The annual allocation now averages about $2 million.

“It greatly limits how much you can do out there,” he admits. “We’re proud to say we’ve made the biggest bang for our buck. The need is there, the desire is there; you just kind of roll with the punches and make the best investments you possibly can.”

Golden LEAF, meanwhile, received no settlement funding in 2013 or 2014, according to an audit last year.

In 2013, the Republican-controlled Legislature began folding the money into the state’s general fund and allocating only a small portion for the originally intended purposes. “There was a lot of antipathy toward these two funds,” says Ager, a Democrat, citing partisan politics. The settlement agreement didn’t stipulate how the money had to be used, and cash-strapped legislatures in other states have taken a similar approach.

Golden LEAF did receive $10 million in settlement funding last year, which enabled it to make more grants. For the most part, though, it relies on the investment income from its endowment, valued at $901 million as of 2013, which resulted from the substantial settlement payments received in the early years.

Reeves, however, says she’s tired of all the politics surrounding those funds. “Golden LEAF and Tobacco Trust Fund could do so much more if the state hadn’t redistributed the money,” she contends. “We’re lucky we got a livestock market out of it and the poultry slaughterhouse, but if they’d kept the tobacco funding the way it was originally, they’d be able to support the farmers more and bring more certainty back into this area.”

Cloudy future

Two years after the buyout payments ended, farmers and agency officials alike have mixed opinions concerning the program’s overall impact. “The USDA thinks it was a good thing: It hit the objectives they wanted it to. It got the government — or, at least, got people to finally believe that the government was out of it,” says Zink. “Me, personally, I would have liked to have seen [quotas] stay on, because I’ve seen what it’s done to the economy in Madison.”

Duckett thinks the buyout “was probably the best deal we could get at the time. It got the growers some payment for a resource they’d come to count on.” And while he wishes that there’d been a dependable substitute crop for tobacco, “Unfortunately, I just don’t think that animal exists.”

For Upchurch, the final assessment is “subjective, depending on what situation you were left in. Farmers in the west were forced to find some new enterprise to maintain their farmland and that income they depend on. It’s been challenging for them, but we’ve seen a lot of innovation.”

Most folks, though, seem to agree that in WNC, tobacco’s glory days are over.

Duckett, for example, says: “I think that ship has sailed. There’s so many parts of the world that grow burley tobacco, and we have no way of competing with them on labor costs. Of course, nobody knows the future, but I don’t see the conditions ever allowing tobacco to be the go-to crop that it once was.”

Still, Duckett and others stress local farmers’ resilience. “If you work the land for a living, you’re tough and resourceful by definition,” he points out. “The buyout really brought that out in people, and the cooperation among growers in general, in learning and sharing ideas, has been great.”

Community-supported agriculture, for example, “was something I thought would never work initially. I didn’t think people would pay up front to get what you get from the grocery store. I’ve happily eaten crow on that.”

Duckett also cites the rise of the local food movement and programs like WNC Farm Link, which connects aspiring farmers with those approaching retirement and hoping to preserve their land for agricultural use.

Upchurch echoes that optimism. “There’s a lot of creativity there, a lot of people willing to try something new,” he says, noting that the small scale of the region’s farms has given local farmers “a better comfort level with taking chances and applying opportunity.” And in the coming years, he predicts, “You’re going to see a big, diversified list of ideas in western N.C.”

Zink, meanwhile, advises those still struggling to find new revenue sources to try “whatever suits you best. Any producer that comes into this office, that’s the first thing we look at: What type of farm do you have? They need to try and find what works for them.”

Good historical article with current challenges of distribution of settlement funds!

FYI, Since opening in March of 2011 WNC Regional Livestock Center has sold (round numbers) 80,000 head of cattle for $70 Million and when multiplied by a consertive 1.5, the local economic impact is $105 Million! An awesome return on the $3.2 Million capital investment of which $2.0 million was from the tobacco settlement!

L T Ward

Volunteer Project Manager, WNCRLC

For WNC Communities , a 501c3 org.

Check us out at wnccommunities.org for more current initiatives!

Hi L.T.! Thanks for commenting and sharing. I appreciate you providing some more in-depth stats on just how important the WNC Regional Livestock Center is for this area. 105 million is quite the return on a 3.2 mil. capital investment! Great to see such solutions and projects are helping farmers and the whole community.

It is time to bring back hemp growing in North Carolina. The products that can be produced form this plant dovetail perfectly with our construction and textile industries.

Hey Tom, thanks for commenting! Hemp cultivation was mentioned by several of the folks interviewed for this article. While it would certainly be an avenue for some farmers to explore, a few people I spoke with had reservations regarding devoting resources towards such an operation, due to the tenuous legal nature of the plant as of now. Definitely an industry to keep an eye on though, for the reasons you mentioned.

I worked with burley tobacco farmers from 1983 to 2006 through North Carolina State University. We conducted on farm tests through the Cooperative Extension Service in as many as sixteen counties throughout my employment. Thank you for this well written article. It brought back a flood of memories. While it saddens me to see tobacco die in Western North Carolina, I’m glad the agricultural community is adapting to new methods for sustaining the farms in western North Carolina. Several of the farmers and county agents I worked with were not just working colleagues. They were my friends.

Hey Scott. Thanks for sharing and reading! I agree that it’s a bit bittersweet to see such a culturally important crop fade away. I think you touched on a very important point: these folks aren’t just “tobacco farmers,” they’re our neighbors, friends and important contributors to the culture and economy of this region. Whatever one’s feelings about tobacco are, we can’t lose sight of the fact that for many, it offered a way of life that is no longer viable to most farmers. But as you said, it’s great to see so much innovation and perseverance on the part of farmers and agencies to keep agriculture a viable enterprise in the mountains.

We lived in eastern NC and my daddy was a buyer for the American Tobacco Co. He spent winters

In Ashville on the burley market, fall in Kinston, and summer in Lake City, Florida. His grandfather was a pioneer in curing bright leaf tobacco in Southern Virginia. While those times are bygone, they are certainly a part of my history and many others of my generation and that community is dearly missed.