On April 10, a recently restored Class J 611 steam locomotive will crest the Swannanoa Gap near Ridgecrest, carrying roughly 800 passengers toward Biltmore Village. The special excursion train, sponsored by Norfolk Southern Railway and the North Carolina Transportation Museum, will offer passengers and bystanders along the route a glimpse into Western North Carolina’s past, when the railroad dominated travel to and from the mountains. [EDITOR’S NOTE: See the gallery at the end of this article for pictures of the April 10 Class J 611 steam locomotive excursion train by Asheville photographer John Haldane or visit haldanecreativeart.com for more.]

Passenger rail service west of Salisbury ended in 1975; since then, local freight service has declined from 22 trains a day in the 1990s to just a handful today. And with Norfolk Southern in the midst of a major restructuring while simultaneously fighting a hostile takeover bid, the industry’s future seems uncertain.

Nonetheless, WNC residents, public officials and the state Department of Transportation are continuing a decadeslong push to bring back passenger rail service to the region. For more than 20 years, the WNC Rail Corridor Committee has worked tirelessly to prove the economic viability of restoring the historic rail link between Salisbury and Asheville.

And with younger travelers showing increased interest in train travel, the committee is changing its approach. Partnering with towns and municipalities and freight rail companies, the group is pursuing a new, three-pronged strategy to realize its long-standing dream.

A long-running love affair

“I’ve always loved trains,” says Judy Ray, the driving force behind the campaign since the mid-1980s. “When I was younger, my brother received a train set for Christmas. I told him it was mine, since I was older, but that he could play with it,” remembers the Asheville resident, who chaired the rail committee from 1995 until last year.

Ray’s enduring passion reflects the railroad’s grand historical legacy here (See “Coming Round the Mountain,” July 1, 2015, Xpress). From the late 1880s until World War II, the railroad was the primary means of access to the region, spawning a massive expansion of the lumber, mining and tourism industries from Asheville to Hot Springs, Saluda to Old Fort.

Many of the towns involved in the current effort were built around rail lines, notes Marion resident Freddie Killough, a longtime committee member. “That changed the dynamic of those communities and brought access to travel. I think they feel a strong connection to their heritage there.”

In the second half of the 20th century, however, the coming of the interstate and the rise of automobile and air travel elbowed passenger trains aside. And as the lumber and mining industries moved west in search of raw materials, the railroads’ prestige and influence suffered.

But that didn’t faze aficionados like Ray, who doggedly defended the trains’ cultural and economic significance. As chair of the Asheville chapter of the National Railway Historical Society, Ray initially pushed to have the city host the organization’s annual convention.

“We were a relatively new chapter, established in 1986, and in ’89 we were holding the convention,” she recalls. “And it was the best one ever, by most accounts.”

The event drew more than 600 people, including such high-profile participants as Asheville Mayor Lou Bissette, Gov. Jim Martin and the presidents of Amtrak and Norfolk Southern.

Lining up support

Over the next six years, the group organized periodic excursions in and out of Asheville, sometimes in cooperation with the Charlotte chapter.

Then, in 1995, Ray organized the WNC Rail Corridor Committee to push for restoring regular passenger service. The organization lobbies state officials, municipalities along the proposed route and Amtrak, hoping to formulate a strategy for achieving this goal. In its first years, the committee collected 140 resolutions from entities across the region endorsing the idea.

“About 20 or so different communities have pledged their support in one way or another,” says Ray, including Old Fort, Valdese, Hickory, Conover, Marion, Morganton, Black Mountain, Statesville and others.

Meanwhile, Ray and her group were also working to expand opportunities for rail excursions, organizing many special trips to Asheville and other localities, and encouraging those towns whose old depots were still standing to renovate them in preparation for future passenger service.

In 2000, the Asheville City Council came on board, establishing its own Passenger Rail Service Action Committee, now defunct. The N.C. General Assembly also stepped up its involvement, appropriating funds for the DOT to begin studying possible routes.

Completed the following year, the study recommended, as a first step, establishing a thruway bus service between Asheville and Salisbury, to gauge the level of support among commuters. Amtrak’s thruway services use buses, vans, ferries or taxis to link rail lines with areas outside the system.

Things were looking promising, but a string of bad luck — the double devastation of hurricanes Frances and Ivan in 2004, subsequent state budget shortfalls and the 2008 recession — caused the DOT to shelve the project until recently, notes Killough.

New directions

Despite those setbacks, however, the Rail Corridor Committee has kept plugging. And during a March 2 meeting at the Asheville Area Chamber of Commerce, the group marked a crucial turning point in both its focus and leadership.

After two decades of devoted service, Ray stepped down as committee chair due to health concerns. In recognition of her work, she was given a special memorial plaque — and a standing ovation.

Moving forward, the committee will be co-chaired by former state Rep. Ray Rapp and Marion Mayor Stephen Little. A new three-pronged strategy calls for collaborating with the freight rail industry, expanding the economic viability of excursion trains and revisiting the thruway bus service idea.

“We have a new vision for the new reality of railroads,” Rapp announced at the meeting, adding, “The rail industry is in a major reorganizational flux right now.”

And if Canadian Pacific Railway succeeds in taking over Norfolk Southern, ownership of local lines would change, a possibility the committee is watching closely.

“It’s a very fluid situation,” says Rapp. “Another thing to recognize is that Class A railroads, like Norfolk or CP, are primarily focused on long-haul service: long trains, typically 100 to 200 cars, carrying the same commodity.”

Meanwhile, control of the local rail corridors is beginning to shift to new short-line operations. In 2014, Blue Ridge Southern, a subsidiary of the Pittsburg, Kansas-based Watco Companies, bought more than 91 miles of track from Norfolk Southern; the company currently has 10 locomotives pulling freight between Asheville and Sylva.

“Who knows what they might be willing to entertain as they get their feet on the ground in WNC?” muses Rapp. “There’s no telling how much additional trackage they might purchase.”

DOT studies have shown that revitalizing freight rail lines also opens the door to more grants as well as federal and state funding opportunities, says Cheryl Hannah with NCDOT’s Rail Division. “Freight leads the way to other possibilities,” she explains.

And money aside, developing stronger links with the freight companies “could encourage excursions and the development of tourist lines,” argues Rapp, adding that it’s time to reach out to industry representatives and include them in the committee’s discussions.

Branching out

The Craggy Mountain Line also seeks to blend the railroad’s historical legacy with present-day needs. Founded in 2001, Craggy Mountain owns roughly 3.5 miles of track between Asheville and Woodfin, offering short excursions in restored rail cars.

The nonprofit is currently looking to expand its operations, founder Rocky Hollifield reports. “I’m negotiating with Silver-Line Plastics and Norfolk Southern to take over some freight service,” he said at the March 2 meeting. He also talked about developing a relationship with Curbside Management, a neighboring business, to help move the recycling company’s materials.

Eventually, Hollifield hopes to develop a museum explaining the Craggy Line’s historical significance. He’s also reaching out to local nonprofits to explore ways his operation might assist with things like temporarily storing and helping distribute surplus food and other items.

In Rapp’s eyes, operations like Craggy Mountain are a promising way to advance his committee’s overall mission. “We need to help folks like Rocky and Blue Ridge Southern by acknowledging the economics of the rail business,” he maintains. “That means involving key players. If we can do that incrementally, we can achieve this.”

Real-world feel

The second prong of the Rail Corridor Committee’s new approach involves expanding the economic viability and frequency of excursion trains. Usually organized as special events, these periodic outings “give folks a real-world feel for the experience of riding the train,” says Rapp.

He believes they can play an important economic role, both for local businesses and the community as a whole. “If we develop, for example, a wine train or beer train, or trains for special events, it provides an economic stimulus for businesses along the line.”

Elsewhere in the region, two long-running operations testify to excursion trains’ viability: the Tweetsie Railroad, near Blowing Rock, has been revitalized as a Wild West theme park; the Great Smoky Mountains Railroad, which operates out of Bryson City, offers tours through the Nantahala Gorge and along the Tuckasegee River.

Right now, excursions on the Asheville-Salisbury line happen only once or twice a year, but Killough says they sell out quickly. She thinks there’s sufficient demand to support running them quarterly, or perhaps several times during spring and fall.

“We want to make sure those folks who want to experience the beauty of the rail, especially coming out of McDowell County into Buncombe, get to experience that,” she adds. “The places it goes in WNC, you can’t get to in any other way. We’d love to see a little more access to that.”

Road meets rail

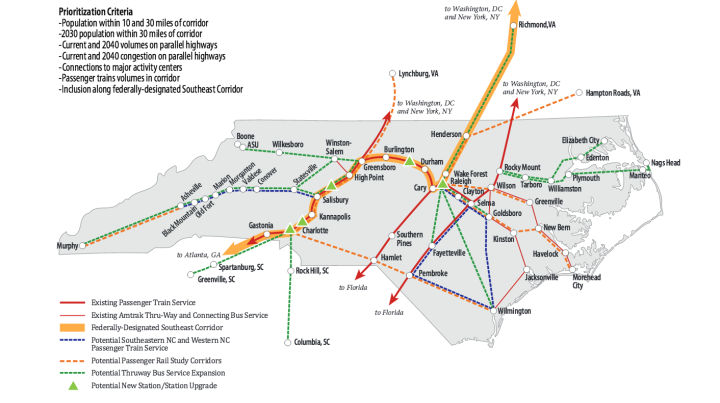

Perhaps the most intriguing facet of the committee’s plan, however, involves renewed talks concerning bus service from Asheville to Salisbury. There, riders could link up with either the Piedmont Line, which runs between Charlotte and Raleigh, or the Carolinian, which continues up the East Coast to New York City.

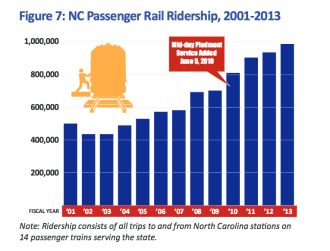

A similar program in eastern North Carolina, connecting Wilmington and Morehead City to the Amtrak station in Wilson was introduced in 2012 and has exceeded expectations, according to NCDOT statistics, with ridership growing each year. Rapp agrees, calling it “phenomenally successful.”

In Salisbury, travelers headed to Asheville (or points in between) would buy a ticket through Amtrak. Buses would run one or more times a day, making stops at designated towns en route.

The hybrid system would enable riders to travel from Asheville to major cities such as Boston, New York, Atlanta and New Orleans, notes Rapp. “The idea is to build traffic for the train service. And then, when you get to a critical mass, they may agree to go ahead and provide rail service from Asheville to Salisbury.”

Amtrak projects 160 daily riders for such a system, which is comparable to the initial expectations for the eastern thruway service. The railroad is considering two models that would offer connections with some or all of the Carolinian and Piedmont trains, with significant waiting time in some cases. Depending on the model chosen, cost estimates run from $300,000 to nearly $1 million a year. Initial ridership is pinned at roughly 12,000 to 16,000 people annually.

A growing need

A comprehensive statewide rail plan the DOT released last August recognizes the need for some kind of Asheville connection. “Metropolitan areas not currently served by passenger rail, such as Winston-Salem, Asheville and Wilmington, are projected to have a significant share of North Carolina’s population growth” over the next several decades, according to the report. “Extending rail services will help ensure the economic vitality of these regions.”

And as Asheville’s tourism industry continues to boom, state officials and committee members alike see the plan as a way to help alleviate the city’s persistent traffic and parking issues.

“The growth in North Carolina’s urban corridors contributes to the traffic congestion along key highways,” the 2015 study notes. Meanwhile, in the last 12 years, “North Carolina rail ridership has increased 93 percent, outpacing growth in population and vehicle miles traveled.”

And though most of those riders are in central North Carolina, Rapp believes passenger rail could bring multiple advantages to Asheville. “I think there’ll be huge benefits for travel and tourism,” he predicts. “As our roads continue to be clogged, people are looking for alternatives to everyone driving from point A to point B, so it’ll also have a very positive environmental impact.”

Meanwhile, anticipating such a possibility, the city of Asheville has factored the bus/rail service into its plans for a multimodal depot at 81 Thompson St. in Biltmore Village, as part of its larger riverfront redevelopment initiative.

“The Asheville station was planned to be near Biltmore Village and was envisioned to serve as a regional, multimodal transportation hub,” says Historic Resources Director Stacy Merten. The target site, which is co-owned by the city and the DOT, is adjacent to the old Biltmore Village depot, which is now the Village Wayside Bar & Grille. At this point, however, there’s no firm timeline or funding for the project.

Meanwhile, the DOT also seems to be on board with the idea, at least in theory. “Extending rail service to the western part of the state,” says Hannah Davis, multimodal communications officer for the state’s Rail Division, “is a goal for NCDOT. We’re working with Amtrak and local communities to look at feasibility and establish a funding source that would allow us to offer passenger rail service to the area.”

Money matters

Moving forward, says Rapp, finding a way to pay for it remains the key issue. “There has to be funding to supplement the operation of that service, or Amtrak won’t do it,” he reveals. “We’re going to have to convince the state and our local communities along the route to pony up.”

To that end, the rail committee is studying municipalities’ contributions to the eastern thruway system to get a sense of what level of financial support might be needed. This data will be presented at the committee’s next meeting, slated for June 8 in Conover in Catawba County.

In the meantime, Merten urges residents to “contact local and state representatives; encourage them to make it a priority.” She hopes the coming update of the city’s comprehensive plan will help the issue gain traction.

“We’re a number of years down the road from actually having trains come in,” Rapp concedes, “but it’s important for us to position ourselves strategically to move in several directions.” This, he continues, will enable the project to “take advantage of how we improve our basic freight service in Asheville and WNC, how we make it possible for more excursion trains to be run, and set the stage for the restoration of regular passenger service.”

And despite the undeniable complexities involved, Rapp is confident that the long-term benefits will outweigh the short-term expenses.

“It’s the kind of driver that — from the cultural standpoint of seeing and hearing about the history and culture of our rail service, how it’s transformed the region, to the economic benefits that can be reaped — there’s light at the end of the tunnel.”

For her part, Ray still hopes the committee she helped found will see her dream through to the end. Even though the strategy has changed, she says, “The goal remains the same: We want to see passenger rail service back to Asheville.” And when that happens, adds Ray, “I hope to be one of the first riders on that first train.”

I’d love to see the return of passenger service to East Tennessee as well.

Private investment should work if emphasis is on economic development in ach city and county between Salisbury and Asheville.

There are more than 3 trains a day on this line. would love to see passenger service return.

Asheville should bring street cars back