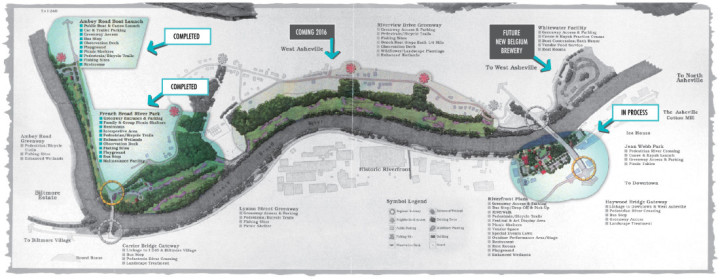

City plans to improve infrastructure, expand public space, increase access and encourage private development in the River Arts District have triggered considerable controversy. In connection with New Belgium Brewing Co.’s $175 million commitment to build a new facility directly across the river, the city broke ground on its Craven Street Improvement Project last year, which includes pedestrian and bike facilities, stream restoration, greenways and parking as well as stormwater management and water line improvements. Since then, however, public debate has raged over the long-term plans for the river corridor, with city officials, prospective developers, concerned property owners and RAD businesses all weighing in.

Opponents argue that increased development in the low-lying district will heighten the risk of flooding, while supporters claim that steps are being taken to mitigate flood risks.

It’s a complex question: Most of the area sits in the flood plain, there’s a long history of large, destructive flood events, and increases in impervious surface will necessarily affect water levels.

In the first of a two-part series, we take a look at the district’s history, some current plans — and what opponents are saying about them.

High water history

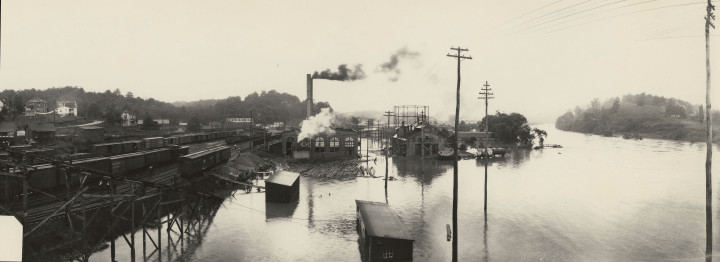

Any consideration of flood risks in and around the RAD must begin with the great flood of 1916, when a succession of hurricanes clobbered the Southern Appalachians. In July of that year, heavy rains falling on already saturated soil triggered a massive flood that caused widespread destruction in the city and across the region. Asheville alone saw roughly $1 million in property damage (about $23 million in today’s dollars) as infrastructure was washed away or buried by subsequent landslides, and some 80 lives were lost.

History repeated itself in September of 2004, when hurricanes Ivan and Frances swept across the Blue Ridge, dumping heavy rains on the area. With water piling up behind the dams at the Bee Tree and North Fork reservoirs, the city decided to open the floodgates, and the combined impact of those events caused both the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers to spill over into Biltmore Village and other areas. While not as deadly as its predecessor, the 2004 flood caused 11 deaths and more than $200 million worth of damage.

“From Black Mountain to Biltmore Village, the floodwaters tore out trailers, stranded livestock and motorists alike, inundated businesses and ruined livelihoods,” Xpress reporter Brian Postelle wrote in a 2007 account of the catastrophe. The article documented the experiences of business owners, who suffered from lack of insurance coverage and lost revenue.

In the wake of the disaster, the city and partner organizations like RiverLink to ramp up efforts to address flood concerns and mitigate future threats.

Earlier that same year, both the city and county had officially adopted the Wilma Dykeman RiverWay plan, developed by RiverLink over the course of two years. Building on such earlier efforts as the 1989 Riverfront Plan and 1991 Asheville Riverfront Open Space Design Guidelines, the RiverWay plan calls for 17 miles of greenways along the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers, with biking and walking paths, strategic development zones within the river corridor, and a re-evaluation of transportation and infrastructure needs in the RAD. Against that background, RiverLink helped secure Federal Emergency Management Agency funding that enabled the city to purchase flood-prone properties in the RAD and laid out plans for mitigating future risks, says Executive Director Karen Cragnolin.

“The Wilma Dykeman RiverWay Master Plan was developed to demonstrate best practices along the river corridor,” she explains. “It has attracted over $100 million in funding and is the French Broad River Metropolitan Planning Organization’s No. 1 priority project.”

Cragnolin maintains that “flooding for WNC is not an ‘if,’ it’s a ‘when,’ and we must be honest about that.” In the future, notes Cragnolin, developers and the city must plan carefully, using the latest approaches to manage stormwater runoff, including limiting the amount of impervious surfaces in and around the RAD and replanting buffer zones in flood-prone areas.

Asheville native Jerry Sternberg, a developer and longtime resident who owns property in the corridor, applauds RiverLink’s renovation efforts, though he acknowledges that he’s often butted heads with Cragnolin and the organization.

“There’s always a dichotomy between the gentrifiers and the anti-gentrifiers,” he notes. “Before they started doing all this, Depot Street was a ghost town and the River Arts studios were just shack-ety old warehouses. I don’t know if they get brownie points for saying we’ve gone this far and don’t want to go further: It’s hard to stop progress.”

Structural improvements to the Smith and Pearson bridges, Sternberg maintains, have reduced the potential for flooding somewhat, and replacing Norfolk Southern Railways’ aging trestle across the French Broad could make a significant difference. “When they changed the Smith Bridge, flooding dropped around my property pretty dramatically,” he reports. “The trestle has such big columns supporting it that it acts like a dam when the river starts getting up. It cuts the flow of the river 50 percent or more, and when debris starts building up against it, it gets so jammed up that water hardly flows through it.”

Riverfront revitalization

In recent years, the long-running efforts by RiverLink, the city and others to convert an industrial wasteland into a vibrant community have succeeded spectacularly. Beginning with an influx of artists seeking cheap studio space in the 1980s, the district has blossomed into one of Asheville’s main tourist draws. Local business ventures like the Wedge Brewing Co. and 12 Bones Smokehouse have become attractions in their own right, gaining national attention and encouraging city and state agencies to support RiverLink’s ongoing cleanup efforts.

“Twenty years ago, very few could imagine the French Broad as it is today,” Cragnolin wrote in a 2014 commentary in Xpress. She points to the many artist-owned businesses, rising property values and the arrival of New Belgium as signs of a bright future for the district.

Sternberg concurs, saying, “It’s working out pretty well. We have the new container restaurant going in down there, and they turned a lot of it into parks, mostly in the flood zone.”

Meanwhile, projects such as Mountain Housing Opportunities’ Glen Rock Apartments and Clingman Lofts have dramatically increased both the number of residents in the area and the support services available to them. The RAD Lofts, a proposed housing complex on the former Dave Steel property on Clingman Avenue, promises to further swell that tally; last August, City Council approved a $764,000 incentive package for the private project. And further planned public investments could spur additional interest in developing the area.

In an interview on “Good Morning America” earlier this year, Pauline Frommer of Frommer’s Travel Guides praised both the revitalization efforts to date and the additional improvements planned, saying things finally seemed to be looking up for the formerly “sketchy” waterfront.

Nonetheless, some RAD property and business owners are beginning to question the wisdom of such rapid expansion in a historically flood-prone area — and the amount of public and private money being invested in the district without proper long-term planning.

Development fears and property rights

“Let me be very clear: We are not opposed to greenways, bike paths, parks and the general overall improvement of the River Arts District,” declares Mari Peterson, chief reporter for the watchdog site ashevillerivergate.com. She and husband Chris Peterson, a longtime local business owner and former city vice mayor, have been vocal opponents of recent proposals to invest millions of taxpayer dollars in what she calls a potential “money pit.” As part of their efforts to resist the city’s plans, they launched the website in March.

“We are property owners and experienced the 2004 flood and the smaller floods before that,” she explains. “There are still substantial flood concerns, and in fact, they’ve gotten worse.”

The Petersons’ concerns stem, in part, from a May 14 announcement by the Asheville Area Riverfront Redevelopment Commission that the city has hired Austin, Texas-based contractor Code Studio to develop a “form-based” zoning plan for the RAD. Established in 2010, the joint city/county body is charged with: making policy recommendations to local governments, promoting investment in the district, reviewing plans for major developments, and working with neighborhood stakeholders. Form-based zoning focuses on appearance and design rather than on a property’s specific use (see box, “What’s Going On?”).

The Petersons and Asheville River Gate are among a number of RAD community members who are questioning the city’s proposals for improving the area, which Mari Peterson says will increase flooding.

“I’m not an expert, but you can read any basic flood information and it basically says that by increasing the amount of impervious surfaces, you increase flood issues,” she adds. Peterson cites the RAD Lofts and a planned parking deck as examples of the kinds of developments that will increase stormwater runoff and raise water levels in the river corridor.

The city, she notes, expects to see roughly $200 million in private investments in the district over the next few years. And one of those projects, alleges Peterson, might be sited on property in the flood plain that the city purchased, using FEMA funding, specifically to prohibit development.

Asked about the charge, Stephanie Monson Dahl, director of the city’s Riverfront Redevelopment Office, says a consultant hired by the city had pointed out that building a hotel on the 10-acre parcel directly across from New Belgium would give the highest return on taxpayer dollars. “It was one of four scenarios, and it’s not the scenario the city is pursuing. The city is not pursuing a certificate to get the restrictions removed, as has been reported.”

Dahl also stresses that the suggestion “wasn’t about breaking federal laws; it was about getting the restrictions off the lands. … The reason you can’t build on it was because of the funding that was used to purchase it. It wasn’t because it’s in a floodway.”

“At this point, the city is not interested in building hotels,” Dahl adds. “The private sector is on top of that.”

Peterson, however, also raises other concerns, claiming that the city and the Riverfront Redevelopment Commission “want to go from 50,000 square feet of developable space to 1 million,” within that protected area. And any developer building on that parcel, she maintains, will want incentives to cover their losses when the next big flood happens.

“The entire area is within the 100-year flood plain, and if you read up on that, it doesn’t mean that it will take another 100 years to happen,” she notes. “It means there’s a one in 100 chance that a flood of that size will happen each year.”

For Bryan King, who bought 12 Bones in 2013, the specter of flooding is a constant concern. “Whenever it rains continuously, we worry and must keep a close watch on the river level,” he says , citing statistics from the North Carolina Flood Risk website.

“Our address is rated high, with an 85 percent chance of flooding in the next 15 years,” notes King, adding that building more structures around the restaurant will only increase those odds. “An 85 percent chance within the next 15 years sounds pretty high to me.”

Chris Peterson owns the property where King’s restaurant sits, which might be condemned in connection with city plans to reroute Riverside Drive. And according to Asheville River Gate, “The cost to relocate them would far exceed what the city would provide.”

Meanwhile, other property owners in the district say the alarms raised by Asheville River Gate and others may be exaggerated.

Sternberg, for example, calls concerns about increased erosion “a little bit Pollyanna-ish. Engineering on hillsides today and the restrictions we have take care of that issue pretty well.” And flood insurance, he notes, “is provided by FEMA and is manageable. Any new building in the floodway has to be built above the 100-year flood level, and utilities must be elevated to meet insurance requirements. If you build to their specifications, the insurance is not prohibitive.”

As for the bigger picture, the octogenarian continues, “It’s not like we haven’t wrestled with these questions for the past 50 to 60 years. There’s always a worry about what we’re going to do to combat the river. She’s a mean old lady when she gets mad.”

Part 2 of this series will consider the physical characteristics of the French Broad River Basin, factors that contribute to flooding, and the potential cost of protecting riverside investments.

Anyone who says that the City is encouraging private development in the RAD has absolutely no idea what they are talking about. Unless you are a hotel, the City has continued its long running policy of strongly discouraging private development within the City limits.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TV4rL62WsfI

Yep…

History didn’t repeat itself, there’s a large difference between 48,000 and 115,000 cubic feet per second of water, both recorded on the same USGS(the government agency who records water levels in Asheville) gauge in 2004 and 1916 respectively. It’s easy to ignore facts when money is to be made. Unfortunately the French Broad will bare the blame and the brunt of ignorance. What’s being built here is an extra large toilet.